Finding a New Path

The shape of what a career as a direct market comics creator might be changing. Let’s look at what that means exactly.

Skottie Young loved Battle Chasers when it launched.

Joe Madureira was his “favorite artist of all time,” and Young wanted to know everything about the guy. The problem was the internet was “barely a thing” at this point. 1 The comic itself was effectively the only gateway to Madureira for a fan like Young, a major source of disappointment for the now cartoonist.

“If Joe Mad had a website,” Young said. “I would’ve bought every t-shirt, bookmark, sticker…everything.”

It was a completely different world at the turn of the century. These days, though, if a direct market-oriented creator like Madureira wanted to fulfill the dreams of a fan like Young — and fund his work while he was at it — it’s considerably easier to do. While opportunities have always been there for industrious, self-starting creators, Young says it’s “easier for everybody to implement almost anything they want” thanks to the robust, versatile options the world now has to offer.

Whether it’s online store architectures like Shopify or Big Cartel, crowd-funding platforms like Kickstarter or Patreon, digital comics entities like Webtoon or Substack, or livestreaming options like Twitch or YouTube, it’s easier than ever for creators to bring their work to fans. Many have been taking advantage of this for years. But for those working within the structures of the direct market, 2 it’s been slower going. That’s for understandable reasons: the cycle of deadlines and finding new work always beckoned.

As someone once told me, direct market creators live on an eternal treadmill, endlessly trying to keep pace. It’s difficult to change the way you do things when your primary goal is surviving and succeeding within that loop. The value of these options was recognized, at least conceptually. But if you have pages or a script due, you focus on the task at hand. That’s why the treadmill needed to break for many to truly take advantage.

22 months ago, that happened. The pandemic hit, and just like that, the direct market changed. Distribution stopped. Publishing schedules halted. And, more crucially to this story, pencils were put down.

And creators had time.

“One of the pandemic effects was that people had a chance to catch that low hanging fruit. They fixed or improved their websites, they set up Ko-fis and Patreons or Etsy, Gumroad, and Shopify stores. Everybody had time stuck at home to level up their game,” The Beat’s Heidi MacDonald told me. “The truth is we have had all the tools. It was just limited by our time.

“And the pandemic gave us a lot of time at home sitting in front of the computer.”

With the direct market effectively on hold and its future deeply uncertain at that point, creators had a choice: wait to see what happens or find a new path. And waiting hardly seemed like an option for many.

That new path — a retrofitting of an enormous mix of tools and opportunities onto the job of making comics — is changing the shape of the direct market creator’s career. This is a look at that path, and how the breaking of that treadmill might have opened the door to a more sustainable future — for those interested in taking it.

When you consider those working in direct market comics, you likely think of writers, artists, colorists, letterers, and beyond hired by publishers. Their prospects are often directly connected to the companies that release the work, and their careers were largely built on surviving (or thriving) within that system…as long as your work sells enough that they let you. Publishers are oriented as the center of the known universe, with everyone else in orbit.

That structure is why this new path is so exciting. It reorients the paradigm back towards the creator, giving them a semblance of control they lacked before. And it’s not altogether different than the one that preceded it. The foundation is the same: making comics, whether it’s for-hire or creator-owned. While nearly everyone I talked to emphasized it’s more important than ever to own your work, storytelling in the comic book form is still the root of this. It’s just adding other methods of funding your work, like crowdfunding, digital comics platforms, merchandising, or whatever, on top of making comics. If it was a math equation, it’d be “comics + x + y + z = your new path.”

The bulk of these options aren’t even new; it’s how they’re structured together with the act of comic making that makes it feel different, and, hopefully, more sustainable for direct market creators. 3 That fusion is more recent, and it helps them more readily bet on themselves. Before, it hadn’t been as necessary. The treadmill was rolling! But as writer Vita Ayala told me, this was “one of those things where necessity is the mother of invention.”

“I think we were poised to start going in this direction already,” Ayala said. “And then the pandemic just made it starkly clear that if you’re not going to do it, you may never have a chance.”

The pandemic simply accelerated trends that already existed. Direct market creators were already looking at these platforms as ways to create self-generated income, even if it was mostly dipping their toes in the water rather than diving in. But with the “uncertainty of the past few years economically” and “the very visible weakness of direct market distribution” in mind, as Polygon’s Susana Polo put it, that curiosity became a full-on embrace.

Much of it gets back to what happened when the pandemic shut everything down. In a snap, projects were paused or erased and creators who believed they had steady work in their future no longer had it. The direct market isn’t like the book market in many ways, but a relevant one here is the lack of advances. That means when the work is gone, so is the money.

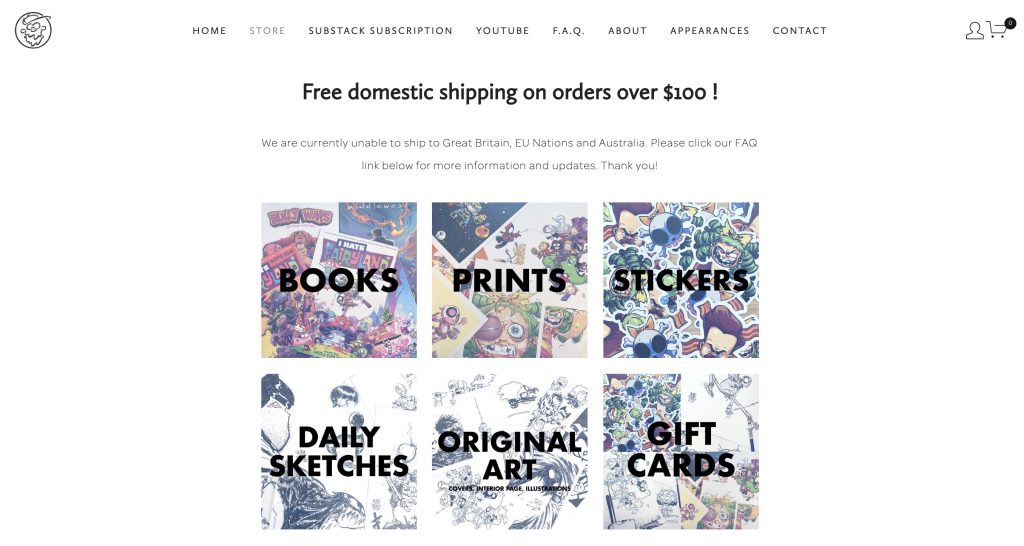

Relying solely on publishers can be a scary proposition. That’s why someone like Young has worked so hard to build up other channels, including his online store, writing efforts, Substack, and any number of other layers: it insulates you from the changing winds of comics. Having options like those allows you to control your own destiny, at least to a degree, giving creators the power to say “no” when publishers once held the power. And when everything broke, structures like Young’s became more attractive to those struggling to find a recipe that was more sustainable.

“The pandemic really pushed (a different system),” writer Joshua Williamson said. “It made people kind of wake up and say, ‘Well, I’m going to try something different.’”

“If there is a positive that comes out of this pandemic, it is that people have started to think about how they can work in a creative field sustainably,” Ayala added.

We might not even learn what the full scope of this will look like for a while. While it might feel as if we’ve been in this pandemic for an eternity, many in comics are still trying to figure what their next steps are. The adoption rate of these efforts has been higher than before, but many are still watching their peers closely before moving in that direction. There’s experimentation going on, and not everyone is a mad scientist. But it’s growing. Polo had a great note about where we’re at in this cycle, describing the acceleration of these trends as “self-perpetuating” at this point.

“The more visible it becomes, the more people realize that they can do it,” Polo said, “And the more people that do it, the more visible it becomes.”

Writer Ed Brubaker said these moves are having “ripple effects” across the industry, as creators look at their peers and wonder why they can’t take this path also. But not everyone can wait. Some creators were no longer just interested in finding new solutions; they needed to. People had to find alternative paths because the pandemic made them realize how little control they had over their own fate. They needed to find answers that worked for them.

The solutions you add to your comic mix depend on the person, if only because there are so many available. The most common answers include crowdfunding – like Kickstarter and Zoop in the project-based space and direct creator support platforms like Patreon and Ko-fi – and varying flavors of social media, ranging from Twitter and Instagram to Twitch, Discord and YouTube. While some of the latter aren’t as easy to monetize, they’re essential to both fostering a connection with and then activating fans, making them fulcrums for your other efforts. These are important for several reasons, but as writer/artist Liana Kangas told me, a big one is they can make the actual job of writing or drawing comics financially palatable.

“We’re trying to make our own paths for substantial passive income,” Kangas said. “At least for me, having passive income, like Patreon and Twitch, is the only thing that allows me to sustainably draw a monthly book or a graphic novel, because we know that page rates aren’t what they should be.”

Digital comics platforms have also become increasingly important channels for direct market creators. The interest in Tapas, Webtoon, and ComiXology Originals amongst previously hesitant creators has skyrocketed, with the most significant example of this being writer Scott Snyder’s deal with ComiXology to produce eight titles under that platform’s umbrella. The Amazon-owned entity has grown increasingly aggressive over the past 22 months, with its surprisingly creator-friendly deal and its agreement with Dark Horse Comics 4 attracting creators.

The ascent on this side comes down to finding potential fans where they are. As Ayala told me, while sustainability is at the heart of this trend, its twin is accessibility. And most new and existing comic readers aren’t necessarily interested in hitting comic shops each week. Engaging with digital platforms like these is a step towards finding a broader audience.

The most notable addition on the digital side, at least from a visibility standpoint, has been Substack. The subscription email newsletter platform has gotten into comics in a major way, with a recipe of immense bags of cash, a deal that allows creators to retain all their rights, and complete freedom during the process that has proven to be fairly appealing. Substack attracted names like Jonathan Hickman and James Tynion IV – with more to come, from what I hear – with their Substack Pro deals, substantial grants that turn each creator into their own publisher 5 so long as they follow an agreed upon posting frequency. Writer Julio Anta described Substack as “probably the best deal because there’s literally no strings attached,” with Brubaker – who declined a Substack Pro deal – emphasizing how unusual and game changing this deal really is.

“What the artists and writers get out of (a Substack deal) is they get to earn a living doing something that they already wanted to do and they don’t have to take side jobs,” Brubaker said. “They get to create these things and have full ownership.”

That’s not an option for everyone. These Substack Pro deals have certainly been aimed towards top creators. But for those who aren’t there yet, simply looking outside the direct market can be beneficial, with eyes increasingly turning towards the arguably far more stable book market. 6 Anta told me “there so many more opportunities right now (in the book market) than what we’ve experienced in the direct market.” He found it particularly appealing after self-funding his Image Comics debut Home, with those publishers eagerly looking for new voices amidst exploding sales.

“The ability to get an advance from the book market, for me at least, has been a total game changer,” Anta said. “As someone who is pretty new in the industry, I’m essentially on a two book a year rotation right now and that’s able to sustain me through the advances that my co-creators and I are getting from the book market.”

While there are other parts of the new creator mix, the last – and perhaps most fascinating one – we’ll go over is merchandising. This has been on the rise for the past decade, as artists like Jen Bartel and Yoshi Yoshitani have built empires that reside at the heart of the Venn diagram of artistry and online commerce. But with conventions largely paused since the pandemic and an explosion of interest within the collector market, we’ve seen this channel get a bit spicier than usual.

Creators sought new answers when conventions disappeared, with online stores filled with shirts, pins, stickers, sketches/variants, or just your own comics becoming staples. With creators losing some or all their income with the departure of cons, they’ve needed to adjust, and many fans have been more than willing to do the same. Some are finding immense success by developing this channel for themselves. It’s even resulted in unusual experiences like private signings, either self-generated or through partners. Fans are normally eager to get comics signed, and creators engaging with these experiences keep them in steady supply in exchange for what is often a nice check at the end.

What all these components look like in concert depends on the person. This path can take on a lot of different flavors. Kangas is one of my favorite examples, as she’s the artist of comics like TRVE KVLT 7 and Star Wars Adventures as well as the co-writer of the TKO Short Seeds of Eden, but also a Twitch streamer, crowdfunder via Patreon and Kickstarter, the artist of an upcoming work-for-hire graphic novel, podcaster, and occasional pop-up online store impresario. 8 Kangas pursues each with a rare vigor and success, but it almost never was. Going into 2020, TRVE KVLT had a deal nearly in place that evaporated when the pandemic hit. Kangas had to adjust on the fly. She learned a lot from the experience, both about how to do these things and what she wants going forward.

“I think my 2020 was the most confusing, stressful and uncertain (year),” Kangas said. “But coming into 2021, it gave me a better idea of where I want my career to go.”

Other favorites include artist Elsa Charretier, someone who has connected her comics fanbase with successful crowdfunding efforts and an incredible YouTube channel, and Young, who was already going before the pandemic but has seen the success of his business Stupid Fresh Mess seemingly become the 1b to the 1a of his actual comics work. They might not offer the playbook for current creators, but they each certainly offer a playbook for others to learn from.

Young’s model brings up a good point, though, in that what it even means to work in the direct market has shifted because of this. Once, they were creators. Now they’re businesses unto themselves.

“All of us are small businesses and you should approach it as a small business,” Williamson said. “And when you are a small business, part of that is diversifying your income.”

The hope is this will make working in the direct market more sustainable. There could even be secondary benefits because of the increased competition this offers traditional structures. Anta sees this as a situation that, ideally, will push publishers to offer better deals. Why would a creator take a deal with a publisher who wants part of your intellectual property in exchange for a page rate, he wondered, when you can keep all of it and still get money up front from Substack or the book market? That’s a good question, and one creators and publishers might be asking themselves.

Now, that pushback likely has its limits. It’s unlikely that Marvel or DC are shaking in their boots right now. Brubaker told me that in his experience, the only thing they “ever look at is each other.” He’s skeptical anyone there is worried about Substack. And like MacDonald said, there will always be someone who wants to work on Batman. That’s why what it does for creators is more than important than what it might force companies to do. It gives creators more power to decide who they truly want to align themselves with.

“I think for the most part, the more money that is out there for creative people to make art, the better,” Anta said, before adding, “Because we can make those educated decisions ourselves as to whose money we take versus whose we don’t.”

While most of these opportunities aren’t risky, there’s always concern about new paths, particularly with venture capital money entering comics via Substack and entities like Zestworld. MacDonald thought being concerned was hilarious, though, sarcastically saying, “Oh my god, people with money are coming into the industry! This is terrible!” But she did emphasize a key point: “People have to watch their ass.”

That’s why most believe that risks can be mitigated by talking to a lawyer and making sure your deal is as good as it seems to be. Ayala summed it up well by saying, “Take the money and go…as long as you are retaining your rights.”

This all sounds amazing, but there is one major downside: taking this path means adding considerable work to a job that’s famously exhausting. Doing this alone is possible, but it’s certainly more difficult. That’s why it’s been unsurprising to see support industries develop around all of this. While agents and freelance marketers, editors, designers, and beyond existed already, their importance has grown during this time. Particularly the former, as MacDonald noted “the rise of the agent” as a huge part of this trend. It certainly was for Anta, who said getting an agent changed finding work from a “long, languishing process” to a formalized, relatively quick one.

Kangas told me working with a marketer or an agent relieves creators of stress and allows for more time that they can spend working on comics. Finding partners that help you focus on the task at hand is something she views as an investment “in your future.”

Of course, there’s one final and massive question at the core of this: does this trend exclusively favor top creators? It’s undeniable that it’s advantageous to have a big audience going in. Having a built-in fanbase attracts big fish like Substack and ComiXology while ensuring a higher probability of success on crowdfunding platforms and even services like Twitch. That’s not a comics-specific trait. As Young said, “It absolutely favors the big names, but that’s no different than any industry.” But it’s still a thing.

Polo had a good point, though: those who are “not top creators have to look at other avenues,” as “they have to build an audience in other ways.” That can be difficult to do. While Kangas believes anyone can benefit from these opportunities, there’s the caveat that it’s going to be “slower and more of a grind” for those who don’t come with pre-existing fanbases. Finding success might take time. But MacDonald cited one of the most successful creators in comics 9 as an example of how this path can lead to significant dividends.

“Who was Rachel Smythe years ago? She came from nowhere,” MacDonald said about the cartoonist behind the immensely popular Webtoon series Lore Olympus. “And now she’s number one with a bullet.”

That’s the ceiling. The difficulty in getting there, as cartoonist Juni Ba told me, is there’s no real playbook for someone that’s new to comics, nor is there an understanding as to what success even looks like.

“It’s a vague and uncertain landscape when you show up,” Ba said. “At least it was for me. I don’t exactly know what I’m doing, so I’m just going to try and do whatever I want to do because I don’t see an actual path.

“And it seems that it’s different for everyone.”

Most think it’s useful to have options available to them, at the very least. Part of finding success with them comes down to being smart about your moves and looking for opportunities where they lie. Ayala said it’s crucial to find “where your demographic is,” saying that will define “where you have to go.” Anta also believes it will open doors for newer creators like himself, simply because the top names can only take on so much work. As they depart from traditional publishers for new opportunities – or just limit their for-hire workload – someone has to fill the void.

It’s also worth noting that this path isn’t for everyone. Not every veteran creator wants to become a business. As Young told me, “That’s not fun (or) natural for everybody.” That can even be the case for new creators, including Ba. The cartoonist told me he “could have gone” down this path, but he didn’t for two main reasons. One was “the allure of the legitimacy of the usual market,” and the other was he wanted to build “a big enough audience that it would carry me to those platforms.” More than anything, Ba just wants to tell stories. So, he’s in no rush to head down this path.

“There’s a bit of a sense of, I have to figure out where everything is and where I fit and which seat actually suits me the best,” Ba said. “And I’m still in that process.”

One idea that came together throughout these conversations was that, in some ways, this new path is a 2022 variant to the Kirkman Manifesto. For those that don’t know, this was a premise writer Robert Kirkman committed to video in 2008, in which he said, effectively, the end game for direct market creators was no longer working at Marvel or DC but taking the audience you built there and getting them to follow you to your creator-owned work. That concept was laid out in a different time altogether, though, as 2008 might as well have been 1961 given all the change that has taken place since.

But the core doesn’t feel incorrect today, even if the components aren’t the same. This new path is similar, except now the first step is basically “make comics or art wherever,” the second step becomes “get work at your preferred publisher” – whether that’s Marvel/DC or Scholastic/First Second/Webtoon – or “build a significant following online,” with the third not just being telling comic stories that you yourself own but activating your audience across every platform of interest to you. On Patreon! On Kickstarter! Through your online store! On Twitch! On Substack! Wherever! It’s still about comics. But instead of purely investing in your comics, your fans are investing in you. And that could allow you to tell the stories you want to tell, faster, if you choose to wait at all.

“For a long time, that took a lot of time to build up to. But now people are just working on their own projects,” Ayala said. “You don’t have to wait and build up all this social capital on top up of sharpening your skills. You can just do what you want to do from the beginning.”

That idea has the biggest appeal to Brubaker. The veteran creator has decades of experience in every part of the business, and he’s excited about this new direction, even if he’s still waiting to see how it all pans out for his peers.

“That’s what I like about this new revolution,” Brubaker told me. “Maybe it’s because there’s a sense that we’re all living through this slow apocalypse of watching the world slowly unwind, but people are like, ‘I want to do this thing and I don’t care if I make a lot of money on it or not and I want to do it exactly my way.’ And that’s something you can do in comics that you really can’t do in any other entertainment form, just a couple people or one person creating a work of art that’s exactly what they want it to be.”

The idea that you can do that and make a sustainable career out of it, without relying entirely on the usual mechanics and gatekeepers that can define your success, is exciting to everyone I spoke to. Kangas hopes “it all starts evolving” in this direction, believing that “we’re going to probably see it happen.” Williamson loves that “there are more resources to try things,” if you’re willing to do the work. Young described it as “probably the best time I’ve seen yet whether or not you’re a big name.”

Anta had my favorite note, though. He feels energized by his inroads in the book market after finding the direct market to be a slog at times, and this trend makes success in comics feel more attainable than it might have before.

“It feels like there’s more room, the doors cracked open a little further for me to get through,” Anta said. “I don’t think that if I started two years ago that I would be at the place that I am right now.”

When the pandemic hit and the treadmill of direct market comics broke, there was genuine fear that this all might be over. Everyone would need to find something new to do, because the system we were used to was going away. Not wanting to do that, clever people like those I talked to realized that maybe it was going away, but only in the sense that they didn’t have to solely rely on it anymore. They didn’t have to be Joe Madureira in 1998; they could be whatever they wanted to be, allowing themselves to connect with die-hard fans like Young so desperately wanted to nearly 24 years ago. And that idea, when combined with the opportunities this era period provides them, could change what it means to make comics in the direct market forever. From experimentation could come empowerment. And perhaps more.

James Tynion IV might be the best example of this trend. He made the decision to leave an enviable gig as the writer of Batman to bet on himself, choosing to tell his own stories how he wants thanks to Substack and others. Not long ago, he told me, “It feels to me like the compass is pointing more and more toward independence at virtually every level of the comic book business,” describing that as “a good, and necessary thing.” It could change everything. But according to Tynion, there’s only one way to make it happen.

“If enough people want to put in that work to the comics industry right now, I think we’re capable of an equally powerful reinvention of our business that repositions us in the broader culture, and we’re capable of doing it in a way that centers the creators rather than the corporations.”

“But we have to want to try.”

Battle Chasers launched as part of Wildstorm’s Cliffhanger imprint in 1998.↩

And by that, I mean the side of the industry built around comic shops.↩

For a lot of newer creators, particularly book market and Webtoon/webcomic oriented ones, this is old hat. They’ve been on this for forever. That’s why this is direct market oriented, because they are, at least to a degree, later to the party.↩

The short version of this deal is Dark Horse is now releasing ComiXology Originals titles in print after they are completed in digital form.↩

It literally says “publisher” in the contract where they sign from what I understand.↩

I’d say inarguable, but I don’t want anyone to yell at me. Also, this is the side of comics oriented around book stores, both online and off, and populated by major book publishers like Penguin Random House and Scholastic.↩

Which she also co-owns.↩

It’s honestly an insane amount of projects.↩

Albeit not a direct market oriented one.↩