The Age of the Limited Series is Here

On the continued shift towards finite titles, and what that means.

Back in the pre-pandemic times, I openly wondered whether miniseries were becoming the new ongoings. Long considered a non-starter, a comparatively unimportant variation to the single-issue formula that inspired trade-waiting above all, minis excelled in 2019 — particularly on the high end. That was a major change from the past, and it inspired questions as to whether a shift was on.

It was a worthy topic to consider, especially at the close of a decade in which DC and Marvel’s endless relaunches effectively erased what remained of the obsessive consumer behavior that came with the litany of long-running, high-numbered ongoings each published. While the ongoing was still the dominant form, the conditioning of comic shop customers had been broken, and along with it much of the loyalty each felt for titles they once loved. That’s why my closing statement was unequivocal: “The era of the traditional ongoing series as the monolithic structure of comics feels like it’s on its way out, effectively buried by the actions of the pair of publishers that once propped it up.”

That was then. And as you may know, a fair few things changed in the nearly three years since.

When the pandemic hit, markets were closed, habits were broken, and, perhaps most crucially, predictable consumer behavior became irregular. Despite that, the market thrived, with increased reader interest and a surge in collector and speculator activity oriented on “key” releases playing a substantial part. Those have been crucial data points in how the market has continued to shift, as each amplified the need to deliver what certain sides of the market needed and/or wanted.

The truth is, what once was a question is no longer one. The limited series – meaning anything that is planned to be finite from the start – is now the 1b to ongoings’ 1a, evolving from a secondary format to a dominant one. Short runs are the name of the game, and it was always coming, pandemic or not. 1

This may not sound like news to you. It has been fairly evident for years, at least to some degree. But how significant has this change been? And why is it happening? And finally, what does it mean? This trend opens an array of questions as a follow-up to the one I explored nearly three years back. Each is worth asking — and answering.

Let’s do that today.

While we all feel like this trend exists, feelings are unfortunately not the same as fact. 2 If this move away from ongoings is real, it should be evident in what’s being published, all of which is available to anyone who wanted to dig through years of solicitations and shipping lists. So, naturally, that’s what I did, exploring several focuses and time periods to provide a varied look at this idea. Before we get into that, though, I wanted to establish the ground rules that dictated how I interpreted this data to ensure you know where it’s coming from.

- For the purposes of this exercise, we’re focusing on anything that’s finite in length, whether it’s five issues or 12, compared to an ongoing, which begin with an undetermined length in mind. 3

- One-shots count as finite. They’re not really a “series” at all, but they’re closer to limited than an ongoing, and they’ve increasingly become a tool publishers use to game the system to some degree. 4

- Reprints do not count as anything. They are not factored in, instead simply being deleted from consideration. 5

- If I couldn’t determine whether a title was an ongoing or finite, I simply didn’t count it.

- To achieve proper volume, I primarily looked at historic data for DC and Marvel. Most publishers simply didn’t publish enough to make comparisons worthwhile.

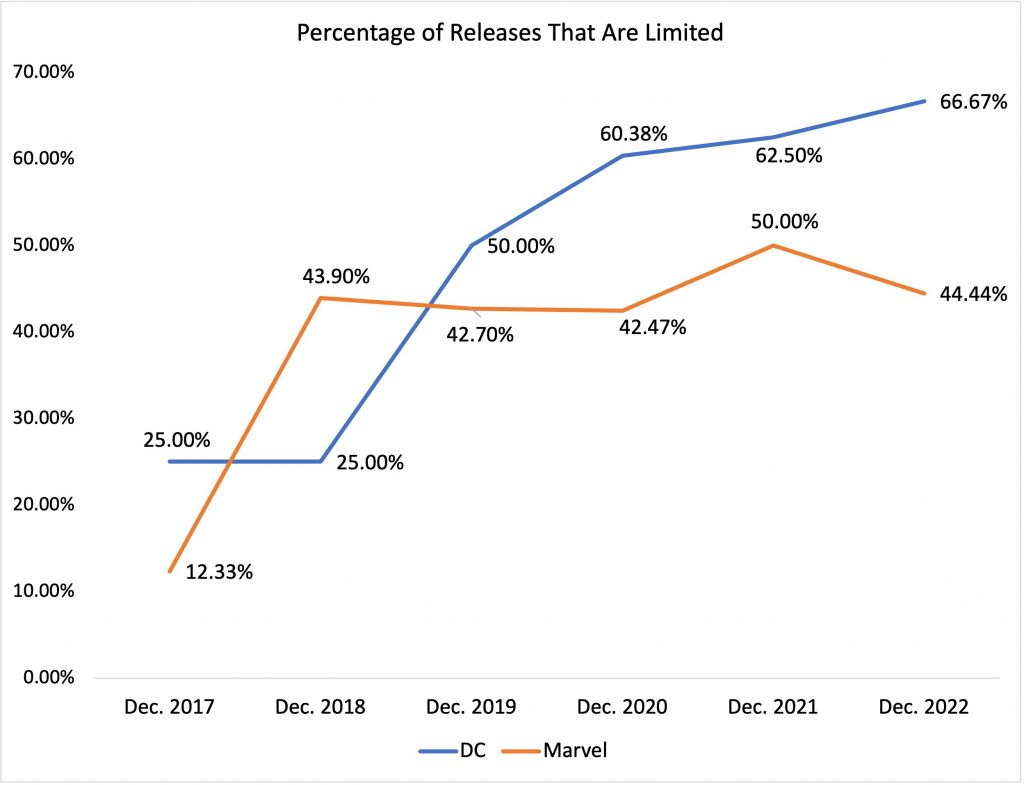

That’s all you need to know to understand the exercise. With that in mind, let’s get to the charts, starting with a comparison between DC and Marvel’s December 2022 release mix — showcasing the percentage of each line that’s a limited series — and the five Decembers that preceded it.

This chart reinforces that while the pandemic may have solidified this trend, it didn’t create it. That’s particularly evident in two places. Both DC and Marvel started this stretch with limited series amounting to a fraction of their releases, with only 25% and 12.33% of their December 2017 releases fitting my criteria. But Marvel’s steep climb in 2018 and DC’s arc upwards right after signifies that each was moving that way before any world events forced their hand.

While the pandemic may not have created this focus on short-run series, it does seemingly act as a line of demarcation, at least for DC. Before the pandemic, DC had yet to surpass half of its line being a limited series. Since, it lives at 60% or more of its line fitting that description. That number only continues to rise, while Marvel fluctuates between 40 and 50% of its titles being finite at any given moment. 6 That difference isn’t too surprising. In my conversations with retailers over the past few years, DC’s commitment to limited series has been noticed.

And it isn’t just the percentage of them that DC leads in. It’s also variations on the formula. There’s no one common look for a DC limited series. They range from one or two issue tales to long-ish, maxiseries length titles that run for between 8 and 12 issues. That latter group is a significant portion of its line. DC is addicted to publishing 12-issue series right now.

That’s a far cry to Marvel’s current miniseries playbook, which – as Marvel’s SVP of Publishing and Executive Editor Tom Brevoort spoke to in his newsletter this week – is largely focused on five issue chunks because it fits the publisher’s approach to collected editions. For all intents and purposes, Marvel still has one foot on the ongoing side of the equation, while 12-issue runs have become DC’s de facto ongoing equivalent outside headliner titles like Batman, Action Comics, and Wonder Woman.

One retailer speculated that this 12-issue structure could become an increasingly regular fixture in the market going forward. I could see that, both for standalone projects and longform stories. The former has a history of use in the industry, ever since the days of Secret Wars and Watchmen. The latter would effectively be the long-discussed season model in comics, offering creators a satisfying chunk to work with narratively while always having a return to the sure-selling first issues on the horizon. DC is already there effectively. I could see Marvel and others studying how that structure works for their competitor and matching it if it succeeds. We’ll see.

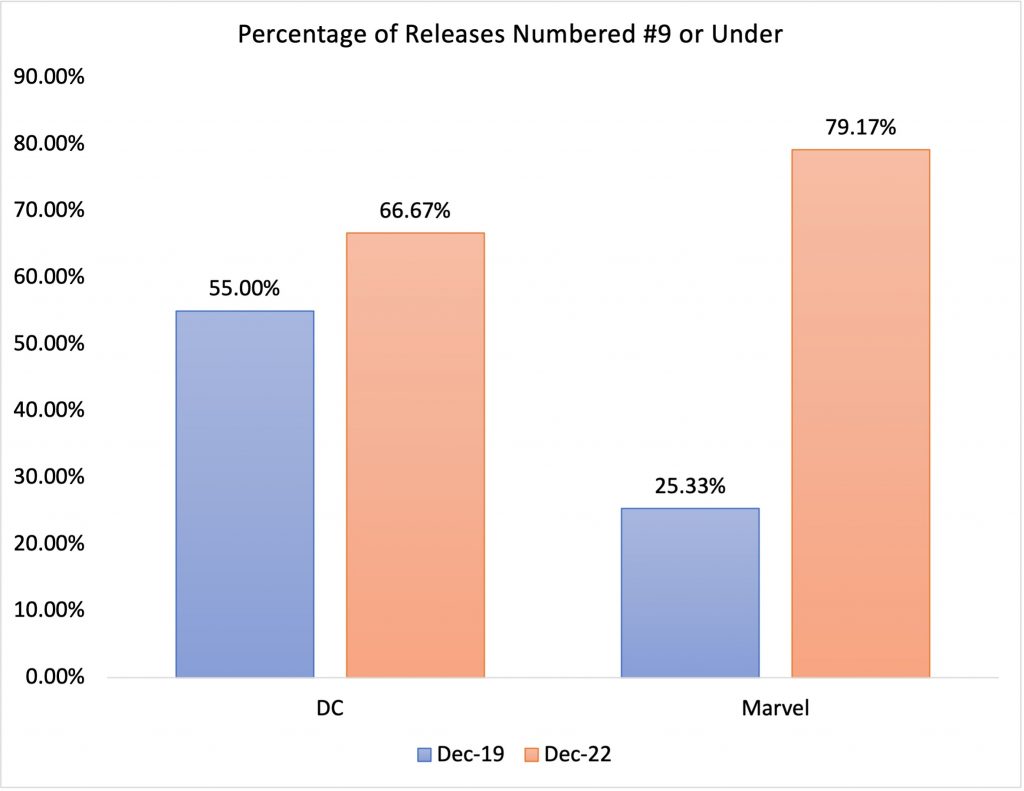

This is only one way to look at how the Big Two are leaning towards shorter runs, though. While Marvel trails DC by a wide margin here, in other ways, it doesn’t. So, let’s look at another chart, which demonstrates the percentage of DC and Marvel’s titles numbered in single digits across two comparable periods.

This might not be terribly surprising. Coming off a series of relaunches, lower-numbered titles are less rare than before. But Marvel’s rise — going from just over a quarter of its line being numbered nine or under to nearly four fifths of them in three years — is staggering. Lower-numbered titles aren’t just increasingly common; they’re the norm. In fact, Marvel’s ongoings largely exist in name only. Save for the occasional series, most of its titles are always on the verge of a new #1.

Times change, obviously, but it’s interesting to compare this period to my youth in the 1990s. Now, the only time a title gets a sales pop is when it relaunches or has a particularly attractive mix of variants. Then, every 25 issues provided an opportunity for a groundswell in interest that both creators and publishers leaned into. Those anniversary-ish issues rarely happen anymore, except when DC or Marvel does some sort of legacy numbering hijinks. How can they in an environment when only eight total Marvel titles were numbered 20 or higher, as is the case this December? 7 These days, the very concept of the ongoing is a myth to some degree. No title is destined to last long.

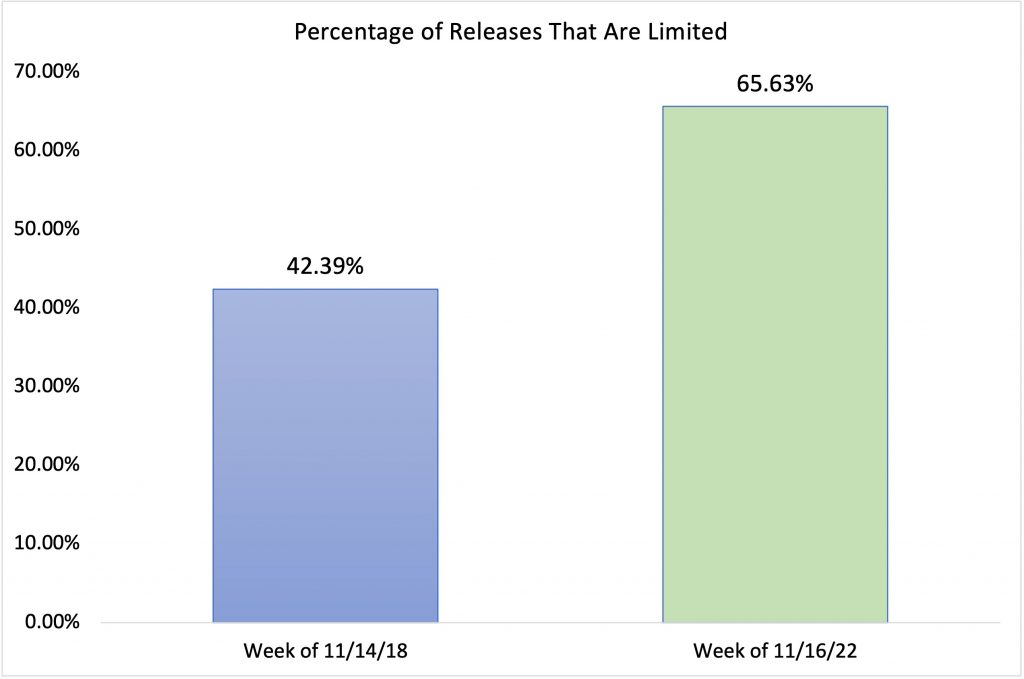

The two publishers at the top aren’t the only ones committing to this trend either. This is market-wide, with this next chart showcasing the percentage of all direct market releases that are finite from two comparable shipping weeks over the past four years.

I hope you’re in the market for a finite series because odds are, almost anything you might buy today or tomorrow will be one. Over 65% of this week’s releases are limited, including 100% of the titles from Dark Horse and IDW, amongst others. It’s clear this isn’t just a DC or Marvel problem, even if the former certainly has its thumb on the scale. Smaller publishers are leaning in hard, resulting in a jump of over 23% from a comparable week four years previous, a number that’s likely understated thanks to one unusual remnant from the ongoing era.

Publishers still seemingly attempt to obfuscate whether titles are ongoings or limited. It’s uncertain if it works. What I can say is it sure is confusing. 8 Scout Comics is the guiltiest party in regards to this tactic. I had to exclude all their books from my math simply because I couldn’t categorize them with confidence.

The likely reason for doing that is there’s still a pervasive belief at comic shops that limited series don’t sell as well. Trying to position your title as Schrödinger’s comic, a series that’s conceivably both finite and ongoing, could be beneficial. The only problem is, despite the explosion of limited series, there’s no clear superiority to that format. They do not consistently outsell ongoings in store, at least amongst those I talked to. 9 Sometimes they do. Sometimes they don’t. But the format does not dictate results.

The truth of the matter is this probably isn’t about one selling better than the other. Instead, it’s more likely publishers managing their floor rather than expanding their ceiling, with this trend acting as a reflection of a concerning development that’s been top of mind recently.

While the shift towards limited series is the result of a series of dominos falling — with DC’s New 52 relaunch arguably the first — what has likely accelerated it of late has been a similar hastening of attrition. That’s been covered at length before, so we’ll keep this brief. For those that don’t know, attrition in single-issue comics is how an individual title’s orders diminish on an issue-by-issue basis. Attrition is typically standardized to some degree, with a largely pleasant slope after issue #2 following the cliff from #1 to #2. The faster a title’s sales drop, the quicker it isn’t viable. And recently, attrition has sped up, resulting in sales dropping at a concerning rate issue-to-issue amongst shops I’ve talked to. 10 That’s obviously a problem.

Maintaining, or even increasing, sales is unusual, which is why managing attrition has long been the name of the game. If you can’t do that — as some are struggling with right now — your options are limited. Today it seems as if the best available are gritting it out as an ongoing series and hoping for the best or keeping things tight by leaning into shorter run titles. And there’s a real advantage to the finite series from an attrition standpoint.

By nature, a quick exit back to #1 is baked into the structure in a way that ongoings lack, and first issues typically sell. 11 Limited series come with built-in insulation from attrition, and a swifter path back to appealing sales numbers. The format might deliver lower potential rewards, but risk is reduced as well. That makes it much more appealing in this attrition-rich stretch we’re in and is believed to be one of the main reasons for the lean in this direction, per shops I talked to.

But this isn’t solely a product of the recent attrition problem, or any single issue, with many disparate ones contributing to deliver us to this point. Again, patient zero remains the Big Two’s obsessive relaunches from the 2010s. These conditioned comic shop customers to trust that if something isn’t working with a title, they can just wait until the next #1 that is surely on the horizon. But it’s more than that. Pair the relaunches with a changing marketplace, a rapidly growing list of publishers with robust catalogs, a black swan event in the pandemic, and any number of micro-events, and you have the perfect formula for change. The attrition issue is just a symptom of something that’s been building for years.

It’s worth noting too that publishers aren’t just releasing more finite series; they’re emphasizing them to a greater degree as well. All you need to do to see that is browse through solicitations of today versus 2019 or before. Minis, maxis, and one-shots used to largely be stashed at the bottom of solicitations for the Big Two, promoted as comparative afterthoughts. Now, they’re often housed at the top. A good example of this can be seen by comparing the December 2017 solicits for Marvel to December 2022. The former takes two releases before it gets to a non-#1, non-limited, non-crossover title; you won’t find something that fits that bill until you’re 15 deep in the latter.

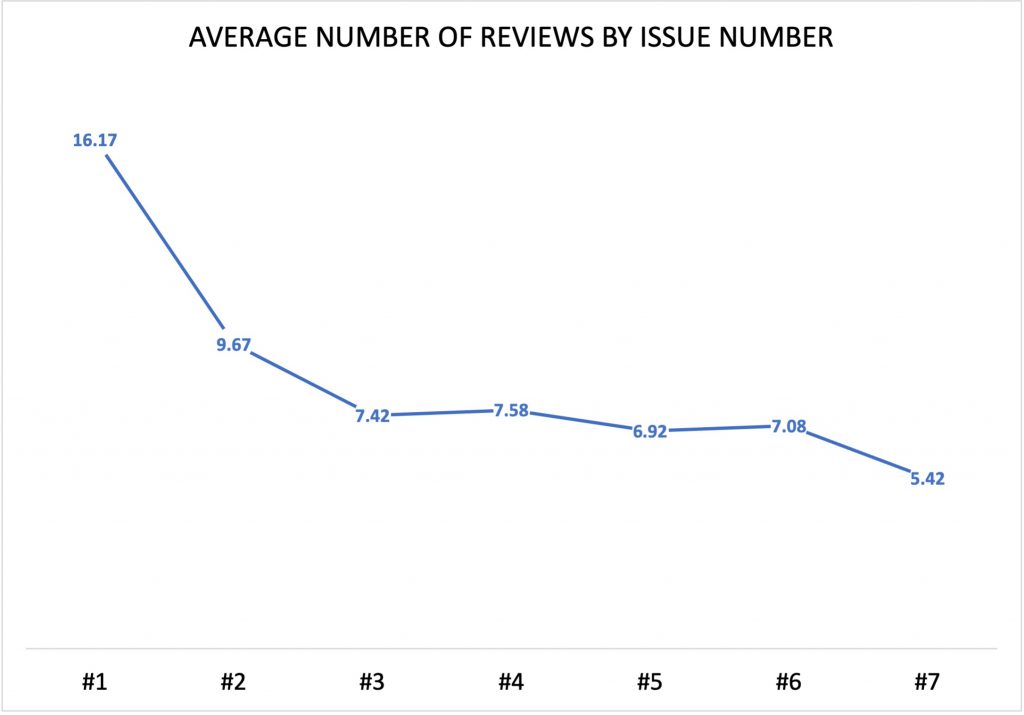

The interesting thing is, all of this — the relaunches, the attrition, the shift in emphasis — is manifesting itself in the larger conversation about comics as well. If a title is 10 issues deep, sometimes it can feel as if it doesn’t even exist. The attention economy is brutal on long-running titles. That’s apparent in how reviews diminish the further a title gets into its run. Here’s one more chart, looking at 12 randomly selected titles 12 and how many reviews they averaged collectively from issues #1 to #7, per ComicBookRoundup. 13

Between issues #1 and #7, the average number of reviews plummeted by two thirds. That’s an immense dip, albeit one not shared equally amongst the titles in my study. The worst off was Robert Kirkman and Chris Samnee’s Fire Power. That title has one of the most notable creative teams around, and yet it was already at zero reviews by #5 with only one since #10. If Kirkman and Samnee can’t get attention these days, imagine being an up-and-comer trying to garner interest.

This isn’t me blaming comic sites, though. The single-issue review game is a painful one, with limited rewards and significant time cost. The only way to get ahead is by leaning into what draws visitors, and readers typically want to know about the new hot thing over something that has existed for a while already. Unfortunately, the answer to what works is rarely a review for issue #12 or #17 or #23. 14 What’s being seen there is a reflection of overarching trends.

More than that, we’ve all been trained by publishers and their marketing teams to pay attention to first issues above all. If those earn all the push from the people who release them, then why should anyone else — reviewers, readers, retailers, whomever — care?

The answer has seemingly become “We shouldn’t.” And everyone is adjusting accordingly.

Whatever the reason for it, it’s hard to deny that a shift is on towards finite series. The only question that remains, then, is “What does it mean?” To diagnose that, we’ll start by analyzing it in isolation: Is this trend a good thing? Is it bad?

One could argue that it isn’t necessarily either.

It nets out as just a thing, a true neutral wearing chaotic evil clothing. The good is readers are given more jumping on points, and shops can pitch customers on more number ones than ever before. As a reader, I appreciate how they open doors to a wider variety of highly focused stories, which can result in interesting, exciting, and unique comics. The bad is that the staccato rhythms of minis are also jumping off points, 15 and when the market is flooded with short-run titles, number ones lose some of the appeal. If everything is a special, shiny debut, then they aren’t special or shiny anymore. 16 Those pros and cons arguably even out in the end.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t exist in isolation. My read on this trend is it isn’t necessarily a reflection of a healthy ecosystem. 17 While there’s a lot of chicken and the egg to the rise of both short-run titles and attrition — and the past decade’s relaunches almost certainly amplified both — the progressive shift away from ongoings has created a dangerously short attention span amongst the people that ultimately dictate the success of single-issue comics: the readers.

Titles that once would have been considered comparatively brief in length – like Jason Aaron’s soon-to-be 63 issues deep stretch on Avengers – last for what feels like an eternity today, with milestone runs becoming millstones in the span of a decade. That’s maybe even especially the case for non-superhero comics. It’s difficult to imagine a title like Sandman or Y the Last Man or even Saga launching today with 60+ issues in mind from the start. I’m not saying it couldn’t work. It’s possible that a lengthy magnum opus could still thrive in this environment. But would any creator that knows the market want to go that direction, and would any publisher want to follow them if they did? 18

It certainly doesn’t help that the lean towards finite series feels like a tacit admission that no one knows how to sell anything but first issues anymore. The saying “You only have one chance to make a first impression” has never been more paralyzingly important to the direct market as it is now. If you don’t hook readers with your first issue, you could be cooked, plain and simple. Publishers have removed the incentive customers had to stick around, that nagging hook of being a completionist. I’d argue that’s a healthy change for readers. 19 But there’s a real cost to that.

That’s not to say finite series are inherently bad or harmful. It can be a powerful form, both from a storytelling standpoint and a sales one. If deployed with a plan behind it, it could be highly effective. Instead, the cost is less about the format than what it means. When the prevalence of limited series is the result of a series of choices and dilemmas that have made the format look like the only option available, it becomes a problem. It starts to look like a self-fulfilling prophecy, even, and one that could limit the possibilities of the stories told in single-issues — potentially forever.

It’s likely only been accelerated by the environment we find ourselves in.↩

This remains as true as ever in 2022, despite how many behave.↩

Or at least it’s outwardly presented that way. I suspect we’re seeing a fair few stealth minis — or announced “ongoings” that have a planned exit back to a mini if the numbers aren’t there — these days.↩

This includes how DC and Marvel have recently been sequencing one-shots in a way that suggests they’re turning a series of #1s into implied minis. That’s the final form of this trend, so they had to count.↩

One interesting note, though: Reprints are far less common in 2022 and 2019 and before, at least from what I saw.↩

Quick note: Just to ensure this wasn’t a random, December only thing, I checked October and November 2022 as well. The splits were effectively the same.↩

It’s worth noting that both publishers are releasing far fewer titles. If you compare the Decembers from 2020 to 2022 against 2017 to 2019, you’ll find 12 and 11 fewer releases per month on average for DC and Marvel respectively. That plays a part here.↩

I cannot even imagine trying to order or sell these comics when there’s zero evidence as to whether some titles are finite or not.↩

This is backed up by ICv2’s most recent sell-through data from ComicHub, with just under half of the top 50 counting as a limited series, with one facsimile edition reprint omitted from the count and the rest being ongoings.↩

Creators have started to talk about it too. Writer/artist Liam Sharp’s recent-ish thread on Twitter about the fortunes of his Image series StarHenge — which, fittingly, is an ongoing comprised of multiple limited series — underlines this well.↩

This is why the season model has always seemed like an eventual end form for single-issue comics.↩

Time Before Time, Little Monsters, That Texas Blood, Fire Power, Black Panther, X-Men Red, She-Hulk, Punisher, Batgirls, Nice House on the Lake, Superman: Son of Kal-El, and Human Target.↩

That site doesn’t map every site that does reviews, just ones with scores. But it’s still a nice standardized guide for this study.↩

Unless there is a change to the creative team or status quo.↩

This also creates a problem of accidental jumping-off points, as shop point-of-sale systems are not always the most adept at transitioning subscribers from limited series to limited series. When it was just ongoings, keeping subs was much cleaner — and consistent.↩

Unless they have a foil variant!↩

There are other factors in play here too, as this piece opens many doors to many issues. I can’t cover everything here. One of them, though, we’ll get to in next week’s feature, which acts as part two to this larger idea in many ways.↩

I suspect this is part of the reason why some traditionally direct market-centric creators are turning a lusty eye towards book market friendly formats and publishers.↩

Sticking with something you don’t like just because you once liked it is not good for you!↩