Relaunches, Reboots, and Rebirths: Comic Books and the Industry’s Growing Obsession with Recency

I’ve been reading comics for around 25 years, and if you asked me what issue brought me into the fold, it’d be difficult to say. Maybe it was Uncanny X-Men #270? Or was it Batman #492? The answer is lost in the sands of time, at least in part because the ongoing numbering of comics gave them an infinite feel. If Rustin Cohle was a comic fan, he might say “time is a flat circle” in the form because to read a comic was, at the time, to be immersed in the illusion of change. All this has happened before and all this will happen again, to quote another show.

These days, the infinite has gotten a lot more finite, or so it feels. Comic books are in an era of reboots, relaunches, rebirths and, most notably, a hearty obsession with recency. No matter what aspect of comics you’re talking about, odds are the conversation is on what’s happening right now above anything else. While that has always been the case to a degree, it has manifested itself in a deluge of first issues and low numbered comics unlike anything we’ve ever seen. While this obsession has coincided with a high time for the industry, it has also led to struggles we haven’t seen before. After all, if the focus is always on the new, how do older comics stay relevant when eyes shift to the next wave?

Look at Si Spurrier and Ryan Kelly’s Cry Havoc for a good example of this. When that series started, it generated 22 reviews for a healthy average of 8.4 out of 10, per Comic Book Roundup. Now? Its most recent issue only had two. That makes sense if it was a comic that had been around for a good long while, but Cry Havoc? It’s only on issue #5. That’s why Spurrier’s going all out to get comic reviewers to pay attention to it.

Maintaining the attention of the press is only one small element of the overall impact this focus on recency has had. In theory, it could affect the sales, orders and potential success a title could have. It could even impact the way comics are told. That’s why we’re taking a look at this topic today, as we attempt to figure out why it’s happening, the viability of ongoings, and how big of a trend it really is. It feels like it is, but is it? Let’s find out.

What the Numbers Say

Before we get too far, the last question needs to be addressed. Are number ones out of control? Is this trend as significant as it feels? Not exactly.

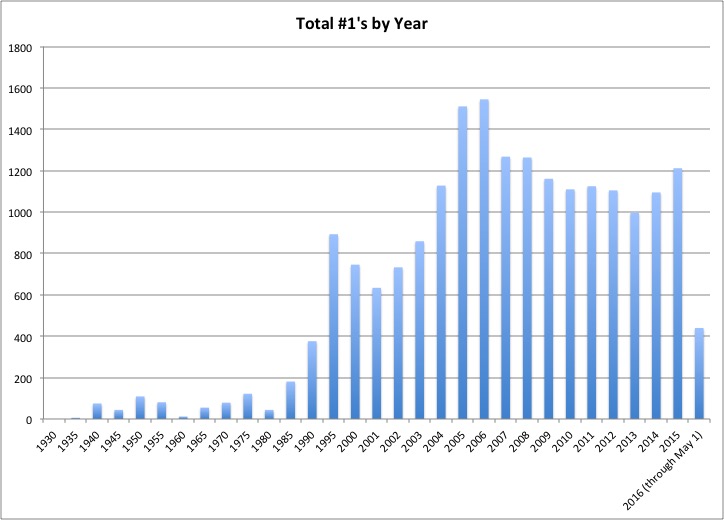

What you see above are the total #1’s in comics by year all the way back to 1930, with year-by-year numbers starting in 2000. The information was provided by Peter Bickford of ComicBase, and it reflects actual release dates, not cover dates. As you can see, we’re not at all-time high levels for total #1 issues. In fact, we’re a decade out from the pinnacle, with 2006’s 1,545 total of #1s surpassing 2015 by more than 300.

When I received this information, I was blown away. I would have wagered a hefty sum on this being the apex of #1’s – and 2016 may still be, as we’re on pace for a record 1,760 – but the proof is in the pudding. The question lingers for me, though: why does it feel like we’re more obsessed than ever with what’s new? Having spoken to a number of smart, connected people about the issue, I knew I wasn’t the only one that felt this way. Could we all be that far off base?

It’s complicated, but one major reason for that is simple. It just isn’t what I expected. There aren’t more debuts now than before. It’s just they’re of a different variety than we used to see.

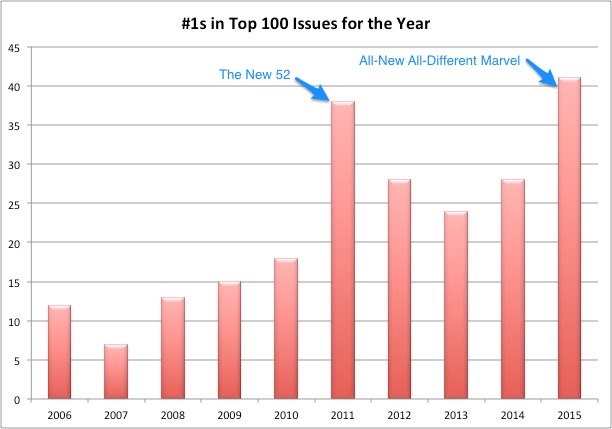

This chart shows the total amount of #1’s in the top 100 selling issues of the year going back to 2006 – per Comichron – and it starts to reveal what we’re getting at. As you can see, #1 issues dominate the top of the chart in a way they previously haven’t. While in years past the top 100 would primarily be the latest issue of this series or that, since 2011 – when the New 52 relaunched the DC Universe – #1’s have become an increasingly utilized tactic for top publishers. 2012 through 2014 saw higher numbers as well, and the Marvel fueled 2015 led to a 10-year high. Forty-one of the top 100 selling comics of that year were debuts.

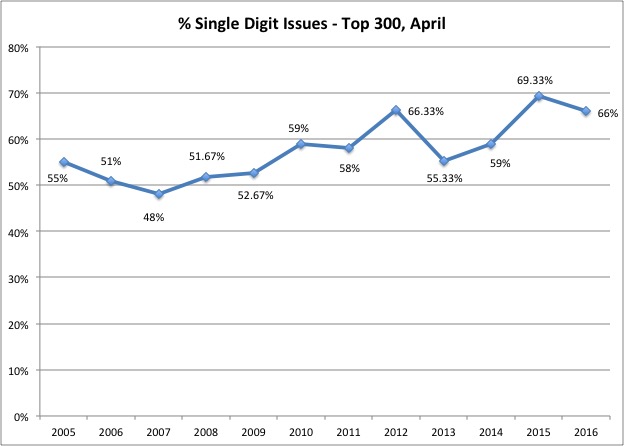

This chart shows the percentage of the top 300 most ordered comics that were numbered in single digits going back every April to 2005. What we see is an upward trending line save for a couple outliers. Ten years ago, only 51% of April’s top 300 were comics numbered in the single digits; in 2016, 66% of them were. So what does that mean, exactly?

These charts show there’s a reason it feels like there’s a greater focus on what’s new, even if the volume of number ones hasn’t increased. It’s because of the companies making the comics that are being launched. In the peak of the number one craze, the bulk were independent or mid-market books. Today, Marvel and DC are leading the way, driven by not quite reboots like Rebirth and whatever exactly the Marvel NOW! redux in the fall entails. In short, the “how many” hasn’t shifted the visibility of this trend as much as the “who” has.

The Reason for the Shift

We know the reality of the situation now, so the question now moves from “who” to “why.” As in, why have Marvel and DC made such a dramatic shift in their practices? One answer is the driver of most business decisions: money. And a second, equally powerful answer to that question is “because it works.”

While some say these “jumping on points” are jumping off points as well – and that’s a legitimate fear – the math favors this methodology. Writer Joshua Williamson (The Flash, Nailbiter) shared the reason for that on a recent Off Panel. He calls it the applecart theory.

Envision there are two competing applecarts where you live. Both applecarts sell the same amount of premium, tasty apples each month – let’s say they each sell one – but in an attempt to bolster sales, one decides that in January, they’re going to put stickers on their apples labeling them as #1 apples. They’re all new, all different, right? The other applecart owner says, “it won’t last. It will get old and you’ll just be back to where you started.”

January hits, and the first applecart sells 10 apples while the other still sells one. The next month, both are selling one again. The other vendor laughs and says, “I told you so,” but when the end of the year hits, one applecart sold nine more apples than the other. That’s a win. Again, the only fear is this could lead to your customers getting frustrated and going elsewhere – it was just a normal apple, after all – and then you’re selling zero apples. But that doesn’t happen, or at least it hasn’t happened yet. That’s why Marvel and DC are running things like they have been recently.

Say what you will about their methods, but it’s a smart move. From a financial standpoint it makes sense, as more orders for their books means more money and potentially less orders for competitors (including each other). Your average comic retailer doesn’t have infinite budget to work with, so choices have to be made. There’s an opportunity cost for each order, or at least for the shops that aren’t Midtown Comics.

Of course, it isn’t just Marvel and DC. Publishers of all varieties have embraced this to some degree. Savvy creator-owned folks like Jim Zub have found ways to game the system at times, as they know a big #1 on the cover can lead to greater orders and even sales in shop. Retailers can attest to that fact, too.

“In general, a new #1 equates to a surge in sales for that title,” said Jen King of Space Cadets Collection Collection, a comic shop in Oak Ridge North, Texas. “We may not like it as a trend, as it relates to garnering readers that will stick with a certain title for the long term, but we have to face the facts. This generation’s readers like the newest shiniest thing. The publishers have figured this out, which is why they do relaunches.”

King shared that in the battle between a #1 or the latest of an ongoing series, walk-in readers will pick the new series any day of the week. She did caution that pull customers are more prone to sticking to a book long-term, though, and that renumberings or creative team changes can lead to them dropping a book. There are trade-offs for each move a publisher makes.

Patrick Brower of Challengers Comics + Conversation in Chicago is a comics lifer, and someone who is admittedly not a fan of this trend. He came into the comics in the 1970’s and looked at the high numbering as a challenge he enjoyed embracing. Still, he’s found what King said to be true as well.

“It is a long-proven fact in the comics industry that #1 issues sell better than other numbers. Whether or not that should be the case is a question for another time, but on the face of it, strictly from a sales perspective, most of these new #1’s sell better than their #2’s, #6’s, etc.,” Brower said. “Only in a few cases, where the quality of the book far exceeds what our expectations were (Vision, Mockingbird) do the subsequent issues sell better than the initial orders of the first issues.”

Economics aren’t the only reason we’re obsessed with “what’s now” in comics, though. It’s a widespread trend, and it permeates into the comics press, social media and more. As writer/artist Mike Norton shared, it’s in part because of changes in society.

“I personally think it’s the general shortening of the world’s attention span,” he said when asked what he thinks is triggering this change. “Immediate gratification in all forms of entertainment has made us crave what’s immediately new.”

Writer Joe Keatinge (Shutter, Ringside) agreed with that idea, citing how human behavior has shifted.

“If you’re out at a party, you’re on Instagram looking at other parties,” he said. “The linear narrative of time collapses into a singularity of social relation.”

“It’s ‘what have you done for me right now,’ wherein the currency of time is completely devalued and if time has no value, creation has no value and people are onto the next comic, TV show, movie, album, author, etc. before one has any time to grow,” he added. “It’s why the majority of all media is focused on known brands and relaunches, not recognizing the root of all those brands and initial launches were original ideas at one time or another.”

It’s the reason Netflix delivers another episode after you finish one and YouTube rolls straight into a related video upon completion of the one you’re watching: they know they might only have you for this moment, so they need to strike while the iron is hot. Attention is fleeting, and it moves to what’s the most readily available over what’s the best.

Beyond that, focusing on the new keeps the conversation on whoever wields it. Spurrier talked about this in a recent piece he wrote, as the press – which generates a lot of the hoopla in comics – spends more time talking about takeoffs than they do landings, or the flight itself. He’s right. A perfect example of what he was referring to unfolded the week of May 25th. That week, Comic Book Roundup shows that 53 sites wrote reviews for DC Universe Rebirth #1 – an admittedly enormous title – while only six were written for Omega Men #12. That disparity would be understandable if it weren’t for issue #12 being that story’s conclusion. More was written about Omega Men when it was thought to have been canceled than when it actually ended.

Like with Marvel and DC capitalizing off how #1 issues perform, I can’t blame comic sites. I’ve been writing about comics for a long time, and I can tell you one unequivocal fact about reviews is a look at a new title will generate more traffic than one for an “old” book. Sites go where their readers take them, and beyond that, the nature of comics and its ordering system begs the eye of the press to focus sometime between today and three months from now.

Likewise, social media’s focus is always locked into what’s immediately in front of it. Whether you’re talking controversy or news, social media’s attention shifts faster than the dogs in Up! when a squirrel is near. One of the core values of Twitter – which is the hub of the ongoing comic conversation, these days – is information being delivered in an immediate fashion. It’s why people are always so upset about the idea of an algorithm on the service: to take away the immediacy is to remove the point of it. So why should the comic conversation be any different?

There’s also the shift in the nature of how comics are read these days. When I started reading comics, there was really just the one way to do it: monthly issues at your comic shop or newsstand. Now? There are apps like Marvel Unlimited or ComicsBlitz, there are digital comic vendors like ComiXology, and there are different formats like trade paperbacks, hardcovers, omnibuses and more. In reality, it’s difficult to get potential readers to pay attention to any single print comic these days, let alone a relaunch. But the latter at least garners consideration for a time.

There are a multitude of reasons for this shift in focus, but the reality is simple. It’s what people want, even if they say otherwise. People love using the phrase “vote with your dollar,” especially in comics. Well, the votes are in: people are in pursuit of what’s new above anything else.

The Death of the Ongoing?

After reading all of that, you might be wondering why a creator today would dive into an ongoing comic series these days. If attention’s always focused on the now, how’s a comic that’s been around for a while going to maintain its stature? That’s a legitimate question, and one plenty of creators are struggling with today, including Norton and writer/artist Tim Seeley.

Norton and Seeley work together on Revival at Image Comics, an excellent series that’s dropping issue #40 this week. You may not think it’s been out long enough for this trend to be impacting it, but that’s where you’d be wrong. Forty issues isn’t that many, but as of March 2016, their comic was the 29th highest numbered comic on Diamond Comic Distributors list of the 300 most ordered comics. That’s wild, and its relative age has made it more difficult for them to keep their audience.

“The longer we go, the less people buy the monthlies, despite the book maintaining the same quality and creative team. It sucks,” Seeley said. “The lesson from readers and retailers seems to be ‘don’t do long form stories (and) please reboot/relaunch’ despite what they say.”

Despite “steady” sales on trades and hardcovers, Seeley is skeptical about tackling another ongoing series after Revival ends with issue #48.

“I don’t think I’d intentionally ever do a long form series again,” he said. “I’m proud of Revival, and I think in the end, it’ll be a success and well-regarded, but I think the era of long-form comic book series is dead.”

“That’s now the domain of every other entertainment medium but comics.”

Norton wouldn’t rule out another longer run down the line, but post Revival, his plan is to work on projects of a more finite length.

“I’ve learned that it’s hard to keep plugging at the same thing for a long time, especially when the audience isn’t always there,” he said.

It’s not just creators that are seeing this trend develop. Retailers shared that customer behavior is shifting away from single issues as the way to buy in the long-term, with walk-in readers embracing trades and a three and out method on new titles.

“I feel like the newer generation of collectors tend to wait for the graphic novels of ongoing titles and (elect) to pick and choose from the racks each week the titles that look interesting to them. That usually equates to the #1’s that have recently come out,” King said. “They will most commonly stick with buying the #2 and #3 of those titles that they liked from those…and then drop them in favor of the newest #1 after that if the title isn’t amazing.”

The three and out method is something Brower sees at Challengers as well. That idea is a frustrating one to creators, as it puts them in a position of having no real control over their success. In ye olden days of comics, people kind of just kept reading ongoings because that’s what they did, whether they were good or not. Now? Even if you’re a book like Norton and Seeley’s Revival – a well-reviewed comic from known commodities – it can be a struggle. And if it’s hard to get readers to pick up #4 in shop, how difficult do you think it is to get them to buy #40?

With the readership trend pushing in that way, one has to wonder whether it’s possible to grow the monthly audience as you move along, especially beyond the first trade paperback. That’s where a choice is often made – keep buying single issues, switch to trades or drop it altogether – and the hope behind trades, especially with Image titles, is that it may inspire readers to buy single issues so they can get the story faster. It can happen, as some books – like Saga and The Walking Dead – have seen monthly readership grow because of collection.

Besides keeping the creators breathing and the comic on schedule, that’s likely one of the reasons Image has embraced the “Saga schedule” – arc, break month, trade, break month, new arc – across its line. The problem is, shops aren’t really seeing that happen. King described increases to readership of titles beyond the first collection as “rare, unless a major story arc appears in the run,” and Brower’s seen the same thing despite the fact his shop is known for being tremendous handsellers.

“This is a depressing statistic for us here at Challengers, and one we wish we could reverse, but subscription numbers never go up after the first collection of a series is released,” Brower said. “Yet, we always expect them to. Surely people will want to be on board the single issues after reading how great the trade was, right? I mean, who wants to wait for at least six more months for the next trade when you can get an issue every month? But it certainly seems that trade buyers are trade buyers and single-issue buyers are single-issue buyers.”

The last point Brower makes starts to reveal why ongoing stories in comics are going to be just fine. While he’s correct in saying some readers work like that, that’s assuming a clean divide between the two audiences that isn’t there; that each format is neatly divided between camps. The reality of the situation is it’s extremely murky. Every reader buys comics in different ways depending on the book and situation. There’s no consistency.

That’s because people are engaging with media in a completely different way these days. Some people buy albums on vinyl and stream playlists on Spotify. Couples might sit down to binge their favorite TV shows via Netflix and excitedly watch others each week via iTunes or Tivo. Movies could be simultaneously released on demand and in theaters. Entertainment is a melting pot when it used to be single threaded.

It’s the same for comics. Because of how multi-faceted our media experiences are now, comics have more diversified revenue streams than ever. That’s why ongoings aren’t dying; they’re mutating. Single issues may sell less in-store, but the ability to make money from a bevy of different platforms and formats allow a series to survive or even thrive at previously unconscionably low monthly sales levels. Look at my piece on John Layman and Rob Guillory’s Chew from yesterday for a great example.

Chew has never been a top seller in single issues. It’s done well, but it’s hardly ever lit the world on fire. But it does have eleven trades, five hardcovers, two massive smorgasbord editions, digital sales and multiple collections in eleven different languages. They have merch, vinyl figures, plush dolls, blind boxes and more. It all adds up. I can’t speak to the exactitudes of their success, but they’ve done quite well for themselves despite their TV deals never working out.

Kieron Gillen wrote about this a while ago, but the success of an ongoing series – especially a creator-owned one – isn’t determined by single-issue print sales anymore, at least not entirely. For many creators, ongoings that aren’t monthly sales dynamos can be profitable – even enormously so – but it takes time. The trick is your comic has to create enough cash flow that you make it to the land of multiple collections. The early days of a new long-term series can be where things get tight, but if you get past that, building a backlist is where you can thrive even as monthly attrition continues to frustrate.

Keatinge has taken the long view with his work, and that’s partially inspired by the path The Walking Dead took after Robert Kirkman and Tony Moore launched it back in 2003. While we know it as a smash hit and veritable media empire these days, its beginnings were far more humble.

“Walking Dead #1 launched at 7,000 (copies ordered) and now sells around 70,000. It didn’t happen overnight either,” Keatinge said. “And no, it didn’t happen (because of) the show. I had a first hand look at its sales trajectory. It was something built over the long haul, in an extremely methodical mix of (most importantly) telling an engaging story, developing a collections backlist encouraging readers of any format to jump on (including digital), and eventually making the right moves when other media came into the picture.”

His greatest takeaway from that book’s success was that if he wanted his book Shutter (with artist Leila del Duca) to succeed, he’d need to embrace a long-term strategy that he sees very few using these days.

“Part of my idea with Shutter was to make it the only original comic book you could get from me for a while, not launching another original series until eighteen months into its life-span,” he said. “By putting my focus on making this one original to last its three acts, the idea is I’ll have something (that) will act as backlist for a real long time.”

“While our single issues are what they are (which isn’t much), we’re constantly selling through on volume one, constantly getting people who read about it online, buy the first issue on Comixology, then buy the first trade from Amazon, then buy the second, third and soon fourth from a comic book store,” he added. “Our soon-to-be-announced foreign licensing deal is in a territory with a readership who might not want to wait for the next volume to be translated after reading the first and then go through this process above.”

“It’s a long term thing – part of an overall five, ten, twenty-year-plan.”

As Keatinge said, it’s working for him, as it is for plenty of other creators. And for what it’s worth, Image Comics publisher Eric Stephenson shared with me in February that while he views the obsession with recency as an issue, it hasn’t led to a decrease in creators pitching ongoings.

“By and large, most of the pitches I get are for ongoing series,” he said. “Writers and artists want to do books that last for a while – that stick around.”

It seems likely that the ongoing form is here to stay. While it’s hard to blame the creators I spoke to who are skeptical, it can still be a successful endeavor if you pick your spots right. But the question becomes what’s going to happen in comics over the next couple years, especially if we continue to see the same deluge of relaunches. King admitted she “does worry a bit about burn out.”

“If there are 20 new #1’s a week, some people might just give up trying to collect comics because it can be overwhelming to them,” she added.

Others I spoke to share those concerns, with Keatinge being the most frustrated with the trend. He described it as “absolutely unsustainable.”

“You can only scorch the earth so much before nothing can grow. We have such a great opportunity now – a readership on the verge of expanding in a big way. And the industry is doing just about everything it can to burn the ties to said readership down,” he said.

Norton views it in a slightly different manner, believing we’re in a “painful adjustment period.” His thought is that we’re in a transition from monthly storytelling to longform stories told in collected form. But in reality, it will probably be a lot more splintered than that. What we’re really doing is moving away from an era of one size fits all comics.

The good news is many publishers are trying to adjust to this new world order already. Image Comics and its creators have made interesting moves to play with the format of their comics, trying to find different answers for the multitude of audiences out there. BOOM! Studios has used what I call “stealth ongoings” to help bolster the audience of titles by using the carrot of upgrading a mini to an ongoing instead of the stick of potential cancelation. Even Marvel’s apparent season model has great potential, even if their strategy isn’t very transparent and it will result in many more #1 issues.

The comic industry – and ongoing comic stories – will be fine in the long run, though. We’re seeing the transition from one paradigm to another, and true to the nature of comics, it’s awkward as hell. But it’s something every medium has either gone through already or is going through right now. Readers are already enjoying the changes we’re seeing. Ultimately, the success of comics and its creators will be determined by finding the right answers to the questions this trend is inspiring today.

Header art from DC Universe Rebirth #1 by Ivan Reis and Joe Prado. Data provided by or derived from ComicBase and Comichron. Thanks to Patrick Brower, Joe Keatinge, Jen King, Mike Norton and Tim Seeley for the perspective for this piece, as well as the select others who helped behind the scenes.