Sliding Doors: A Thought Experiment About What’s Next for the Direct Market, Post Pandemic

If you take even a superficial glance at the world we’re living in today, it’s easy to see we’re in a time of perhaps unparalleled change. All facets of life are being affected and when this is all said and done, one can only hope that the world is quite a bit different. And nothing is escaping these winds of change. Not even a medium of entertainment like comics, or one of its primary mechanisms of industry, the direct market.

Just look at the big markers you can see on the surface, like DC securing alternative distribution options via DCBS and Midtown Comics – ditching Diamond entirely in the process – or both DC and Marvel utilizing digital as a single-issue platform in a more robust way. Moves like those make it feel like there’s a shift upon us, even if other publishers endeavor to hold the line for retail partners. And yet, in conversations I’ve had with shops from around the world – even ones who would typically be considered rather single-issue focused – I’ve noticed a softening of stances on moving forward with the way things work.

While many vocal retailers are resistant to change, others are learning from what they’ve seen and factoring that into how they’re planning going forward. That’s flexibility is significant, especially as change is happening and even greater movement is considered. And it’s all because of how everything we’ve went through in recent months has realigned how we think and do business.

This change was something I was already thinking about, but then, writer/artist Declan Shalvey asked a rather interesting question in my May mailbag that made me consider its shape even more. That question was this: “What possible directions do you imagine the industry will move post COVID-19, like in a ‘Sliding Doors’ type situation?” 1

Given the significance of that question, I punted on answering it then as it isn’t fit for a mailbag; that’s a longform unto itself. Pair it with where my brain was already and I’ve been noodling on it for weeks now. It has grown to become its own thing altogether, a thought experiment with many sliding doors to choose from, continuously evolving as changes mount, like with DC’s recent, monumental divorce from Diamond.

For this exercise, I’ll be projecting outwards from effectively today to five years from now, roughly speaking. That length is enough time for the industry – or, more specifically, the direct market 2 – to theoretically recover and then move towards its next identity, if that’s the direction it eventually heads in. And its eventual shape, what it looks like, is largely dependent on a very specific sliding door: how much publishers commit to digital going forward.

We’ll be considering what I believe are the five most likely paths with that variable in mind, 3 and as the direct market always does, we’ll start with where we were and already are: the status quo.

Scenario One: Business as Usual

The current state of the direct market is considerably different today than it was just a week ago, primarily because of DC’s decision to extricate itself from its long-standing relationship with Diamond Comic Distributors. That was a Sliding Doors moment unto itself. Its decision to leave Diamond and work exclusively with Lunar 4 and UCS 5 as its distributors has effectively changed the future of the direct market and what “business as usual” even means, just with one move.

Before DC’s disillusionment of its relationship with Diamond, I’d have wagered this would have been the most likely future for the direct market and its varying players. After all, if we have learned anything during this pandemic, it’s that the most vocal elements of comics retail will do anything they can to keep the direct market as is. Because of that, their partners will continue to do what they can to make as much money off of them before this merry-go-round stops spinning altogether.

The current state of the direct market is largely defined by Marvel and DC publishing too many comics with too many covers to try and keep up with revenue goals. Meanwhile, publishers outside of the Big Two endeavor to maintain strong relationships with shops either because they genuinely want to, because it leads to gains for them, or due to some combination of both. The problem with this is everyone is always wooing upwards, hoping to attract someone above their station by offering incentives that are designed to appeal to those above them and rarely actual readers.

When that is your formula, you end up with aging business leaders, an aging audience, 6 and business practices designed to sell as much product to shops today even if it’s harmful to tomorrow. Because of that, retailers operate in an extremely risk-averse way, where even high potential gainers like House of X/Powers of X are approached with not failing in mind rather than capitalizing on a hit.

Don’t get me wrong: this is the only way I’ve ever known the direct market to operate. I love comic shops, and I have a great bit of nostalgia for the print single-issue format. But there’s a reason other industries continue to change and evolve with the times, and it’s because nostalgia in business practices – not content 7 – is typically a one way path to relative obscurity. The way the direct market works is similar to what you’d see if the music industry operated with record stores as its leading light. But you don’t see that happen because they’re a niche aspect of a much larger business. They can be a piece of the pie, but everyone knows they shouldn’t be the biggest one.

That’s shifted in comics, as even today, graphic novels comprise a little less than twice as much of the overall marketplace as single issue comics. 8 Graphic novels have taken a stronger hold of the way stories are told in the medium, and that’s led to real gains overall. But in comic shops, single-issues are still king, with comics taking up $360 million of 2018’s $510 million in total revenue for retailers, creating a roughly two thirds to one third split between single-issues and graphic novels. In more forward thinking shops, those numbers are closer to level, even favoring trades and graphic novels in stores with an almost bookstore like experience. But even in those, single issue sales operate as expected, regular cash flow, even if the ceiling isn’t quite as high for them as it is for graphic novels. They are still crucial to the success of even the most progressive shops.

Meanwhile, digital has largely plateaued, with direct download sales bouncing between $90 and $100 million over the past few years despite online experiences thriving in other storytelling mediums. Part of that is because subscription services like Marvel Unlimited and ComiXology Unlimited aren’t reported within that number. From what I understand, those platforms have seen significant growth. Another part if it is because many publishers operate in fear of upsetting comic shops, and a house trying to attain new readers – even new potential long-term print readers – through digital means is a kiss of death to many shops. In the eyes of these retailers, seemingly, any potential gains that could come from wooing younger readers via digital are worth missing out on if it denies any opportunity for the dreaded “channel bleed.” 9

Presuming the relative status quo is kept – either via Diamond and Lunar/UCS going forward in concert, Lunar/UCS stepping up to take on a bigger role, or other distributors entering the fray – the direct market would likely continue to do about as well as it currently does in the short term if business as usual is the direction of choice. That makes this path an attractive one for plenty who do well enough now. Long term, though, moving forward with business as usual feels like a march towards diminishing returns, especially as the audience ages with the single issue form seemingly being anathema to the interests of younger readers.

Scenario Two: Staying Focused on Print, But With Fewer Releases and Fewer Variants

One of the most common complaints I hear from comic shops is something I addressed in the first scenario: Marvel and DC publish too many comics with too many variants. 10 The obvious problem with that is a whole lot of those titles have no clear audience. Without that, they just become sunk costs for shops with little potential for future sales.

Here’s where we get into a quick interlude about the nature of single-issue sales today. With a few exceptions – namely collectors and those titles that eventually are adapted into a film (or star someone that’s going to be in a movie) – new single-issue comics have become effectively disposable, perishable goods. While back issues were once a potent part of your average comic shop, that’s dialed back considerably as modern releases just haven’t had the same kind of shelf life. 11 There’s a secondary market within comics and one that is fertile, but it’s rarely for random issues of recent titles Jason Aaron and Chris Bachalo’s Doctor Strange or Bryan Edward Hill and Szymon Kudranski’s Fallen Angels. These newer releases effectively have value for a week, a change that even led Mile High Comics’ Chuck Rozanski – someone who claimed to once have $1 million in outstanding Diamond invoices 12 – to reduce his reliance on new issues. Without returnability or any mid-to-long term value, even ordering some lower tier Marvel or DC titles can be a high-risk endeavor for shops if they last through the first weekend.

Beyond that, the volume of releases makes it more difficult for shops to order deep on even the titles they believe in. When you pair that with the deluge of variants comics are tagged with, you create a target rich environment for speculators. Titles live and die on sustainable readership, and this situation makes it harder for low-to-mid tier titles to survive very far into their runs at all.

So how do you solve that problem? One path to greater health seems simple: publish fewer titles with fewer variants and promote the ones that remain more. That isn’t a magical cure-all, and the reason it doesn’t happen is because Marvel and DC have revenue goals to live up to. But we’ve seen publishers like BOOM! thrive by putting more into less, with their success sky rocketing on a per release basis. That’s powerful.

Due to the pandemic, we’ve even seen Marvel make significant shifts away from its typical volume of releases in the direct market, choosing to pace themselves in a decidedly un-Marvel like way. Even more unexpectedly, a slew of titles were moved from your standard print and digital releases plus eventual print trade plan to something relatively new for the House of Ideas: digital only for the remainder of their runs before an eventual print collection. Now, that’s circumstance driving the situation, of course. If it weren’t for the pandemic, odds are titles like Hawkeye: Freefall and Jane Foster: Valkyrie would have played out their runs in print before quietly being canceled. Instead, a different path was taken to lighten the load on comic shops and give the titles a shot at some sort of conclusion.

Hilariously, it was poorly received, as now retailers had to explain to customers why they could only finish titles in their pull list through digital means. But this does open up an interesting potential path for Marvel if it actually works. If orders on surviving print titles outperform expectations, perhaps the publisher will attribute the corresponding lift to the reduction of the line. And if they end up earning more off of the lower selling titles that were shifted to digital, maybe that migration becomes an appealing alternative to outright cancelation. There’s opportunity presented by the pandemic in that regard. Could circumstance accidentally dictate a different path?

I’m not sure. It’s such a noisy period anyways with so many shops closed due to shelter-in-place orders and foot traffic diminished or cut off completely. Trying to determine one variable as a driver for an uptick or a downturn is a crapshoot, a guessing game few decision makers at any publisher would like to put their name behind.

But if this path is taken beyond the pandemic’s area of impact, I could see it leading to per title gains for both publishers and retailers, as BOOM! discovered. With fewer titles and more marketing support per release, it could lead to greater discoverability for better books, and digital could be seen as an escape hatch for lower selling titles. It’s an interesting idea, with its longevity depending on Marvel and DC earning enough gains from titles on average to make up for the loss of volume. I’m skeptical they’d get there, or at least enough so to ward off accounting departments who would likely bristle at this kind of long-term thinking.

Scenario Three: Greater Balance between Print and Digital

Right now, there’s a heavy lean towards print when it comes to single issue comics. As noted earlier, digital downloads typically only account for $90 to $100 million per year in the overall comic market, per ICv2, and that’s single-issue releases and trades combined. 13 Because of that and retailers’ enduring desperation to avoid channel bleed – or perhaps the former is because of the latter – digital has been positioned as a supporting product rather than a co-lead, if you will.

But the pandemic has triggered – or at least revealed – some interesting pathways that could lead to greater balance between print and digital. Consider DC’s decision to release DCeased: Hope at World’s End, a bridge title between the first DCeased volume and its follow-up, Dead Planet, as a digital first comic before presumably releasing it as a print collection down the line. You might have guessed it: retailers were displeased by this decision.

I wasn’t. I see it as a high upside, low downside opportunity. This series is just 99 cents per chapter, and given the outrageous success of writer Tom Taylor’s Injustice series at the same price point in digital, 14 I could see Hope at World’s End being the type of release that leads to gains for the digital and print editions of DCeased and its sequel. 15

Now if that happens, that introduces a very fascinating interplay between digital and print as a pathway that’s rarely used. If low cost digital releases lead to gains for higher cost print comics – both for publishers and retailers – then I could see this melting some of the icy feelings retailers have towards digital. Maybe there’s channel bleed, but if there are gains elsewhere that come with it, that could be enough. Of course, it would need to be a clear case of causation rather than correlation, and it’d probably need to be a genuine dynamo to get there. But it’s an interesting test case because that DCeased is genuinely great, Taylor is on fire, and with DC’s move away from Diamond, I could see the publisher’s flirtation with digital first becoming more of a straight up love affair. If Hope at World’s End works, watch out.

Part of the reason retailers fear channel bleed so much is they view the situation as a binary one. It’s all or nothing, one way or another. Now, as retailer Brian Hibbs has told me many times, I’m an atypical reader, but I buy comics as print single issues, trades and graphic novels, as well as digital single issues, trades and graphic novels with subscription services on top of that. Whatever fits best for how I want to read right then. And I don’t think I’m the only one. Consumers are more fluid today than ever.

If digital releases were given more emphasis and a more obvious place in the larger plan of publishers, developing more connective tissue between the varying platforms along the way, I could see this being a nice “have your cake and eat it too” option for everyone. Making digital and print complementary products rather than competing ones feels like a recipe for gains across the board.

I could see this happening. One thing that’s clear to me from the pandemic is that it’s leading to a shift of what traditional thinking of the comics business should be. But retailers would scream bloody murder about this at first. 16 It would require a heck of a sales pitch, and an impactful test case as proof of its potential. Maybe Hope at World’s End is that. Or maybe it’s just DC trying to squeeze a little more out of DCeased before it ends. Perhaps we’ll find out.

Scenario Four: DC leads others to a different version of the single-issue format, with a much greater focus on digital elsewhere

In the past couple months, I went from extremely down on how DC was handling the pandemic to believing they’re the most interesting direct market publisher right now. And that was before they ditched Diamond! They were the first direct market publisher back to market because of their decision to find alternative distribution methods when Diamond closed up for a time. Then they decided to go their way altogether, going exclusive with Lunar and UCS as their distribution partners. They’ve leaned into digital first efforts like the aforementioned DCeased: Hope at World’s End as well as a bevy of other titles. And from what I’ve heard, the wheels have been turning as they developed other tactics beyond the same ol’, same ol’, which seems to corroborated by this intriguing rumor that exhibits a desire by DC to think even further outside the box.

Basically, they’re doing what everyone else should be in a time of wild uncertainty and shifting consumer prospects and sentiments: trying to figure out what might work tomorrow rather than just assuming what worked yesterday will always cut it.

Pair that with the Black Label emphasis from the publisher’s previous 5G plan as a potential outlet for a different form of single issues, and you have a publisher that’s drawing my attention quite a bit lately. The funny thing is early on in the pandemic, I believed this was DC behaving desperately, uncertain what will work so they were trying everything instead. But I’ve softened on that stance recently because when you look at everything as a whole, it…sort of resembles an actual plan. And plans are good!

Consider this. What do we know about the average print single-issue reader? A lot of them are consumers who have one foot in the camp of readers and one foot on the side of collectors. What makes more sense for them as a product: disposable, often forgettable $3.99 releases on paper of dubious quality or premium, prestige plus releases from top teams that might cost a bit more? Probably the latter!

And what likely makes more sense for a digital reader? Someone who is likely firmly planted as just that: a reader, first and foremost? Lower priced digital first releases that are eventually collected as higher quality trades – likely following DC’s standard practice of hardcover initially and then trade paperbacks – with the digital product effectively acting as trailers for the collections for some fans.

When you look at the marketplace for direct market publishers as a whole, it’d be pretty easy to argue that the print single issue market has likely already seen its peak – short of gamesmanship via a higher volume of releases and a deluge of variants – and that digital has significant room to grow. Delivering a higher quality product for the reader/collector via a Black Label-like experience and a lower cost one for single issue readers via digital – before, again, eventual collection into a hardcover and trade paperback in print – could arguably be the closest thing we have to threading the needle in the direct market. And this seems like the path DC is currently looking rather lustily at, especially post-Diamond and with its young adult and middle grade efforts in mind.

I imagine everyone else in the direct market game was watching them with great interest already, but now that they went rogue on distribution, curiosity has almost certainly hit even higher levels. This all makes sense, too. From what I understand, DC has a little more leeway to experiment with loss leaders than others, and because of that, their test kitchen can get a little more spicy. If it works, others could copy that recipe, changing the game in the process. If it doesn’t, it’s easy for everyone else to continue forward with scenario one, with non-DC publishers touting themselves as the ones who stood by comic shops while the Distinguished Competition curried favor with the enemy.

I already viewed this as a high upside scenario with real potential, if only because it requires just one publisher to take the leap and act as a test case, and because the only real way the way the industry shifts in a significant way is if publishers break from the traditional approach. Retailers won’t, and DC is already clearly not opposed to that idea. The problem is, while the best retailers have firmly embraced trades and graphic novels as better long-term earners for them, I struggle to imagine a world where shops willingly get behind a solution where digital is a primary option without proof of its viability for everyone. If DC goes this route and makes it work, they’re heroes. If it doesn’t, shops are mad at them, which they already constantly are anyways.

In for a penny, in for a pound, as they say.

Scenario Five: The Direct Market doesn’t exist, at least not in the same way

In the original version of this article, there were only four scenarios. But with DC breaking up with Diamond, a fifth scenario must be analyzed just because it became a possibility thanks to that move. While I don’t believe it’s likely, DC’s departure makes business more difficult for Diamond, a company that is not quite as liquid as one might expect them to be. They’ve lost 30% of their primary line of business, and if that math eventually doesn’t add up or more publishers migrate, this could bring the end of Diamond Comic Distributors.

Cue cheering on Twitter, but with Diamond’s collapse would likely be joined by the end of a huge amount of comic shops, smaller publishers folding, and others rethinking how they do their business. This would likely result in print single issues largely disappearing with digital and collections becoming the primary method of doing business, beyond what I imagine would be some level of mail-order business via DCBS and Midtown, aka the parent companies of DC’s two distributors. Some comic shops would likely survive, as they become even more like record stores in spirit and bookstores in actuality. But if Diamond fell apart in the near term, I don’t think the direct market would survive in its current form. It would evolve, for sure, but it wouldn’t be 2,500 accounts. At most, it’d be a fraction of what it once was.

This would not be ideal.

Quick note: there’s always the chance Lunar and UCS could pick up other publishers as a life raft and the direct market could continue to exist as is. I’m certain non-DC publishers are mathing out that idea presently, as well as a whole host of other options. But given that we don’t even know if they can handle the current amount of comic shops with just one publisher – that’s a big, looming “to be determined” – that’s a whole lot of uncertainty stacked up against them.

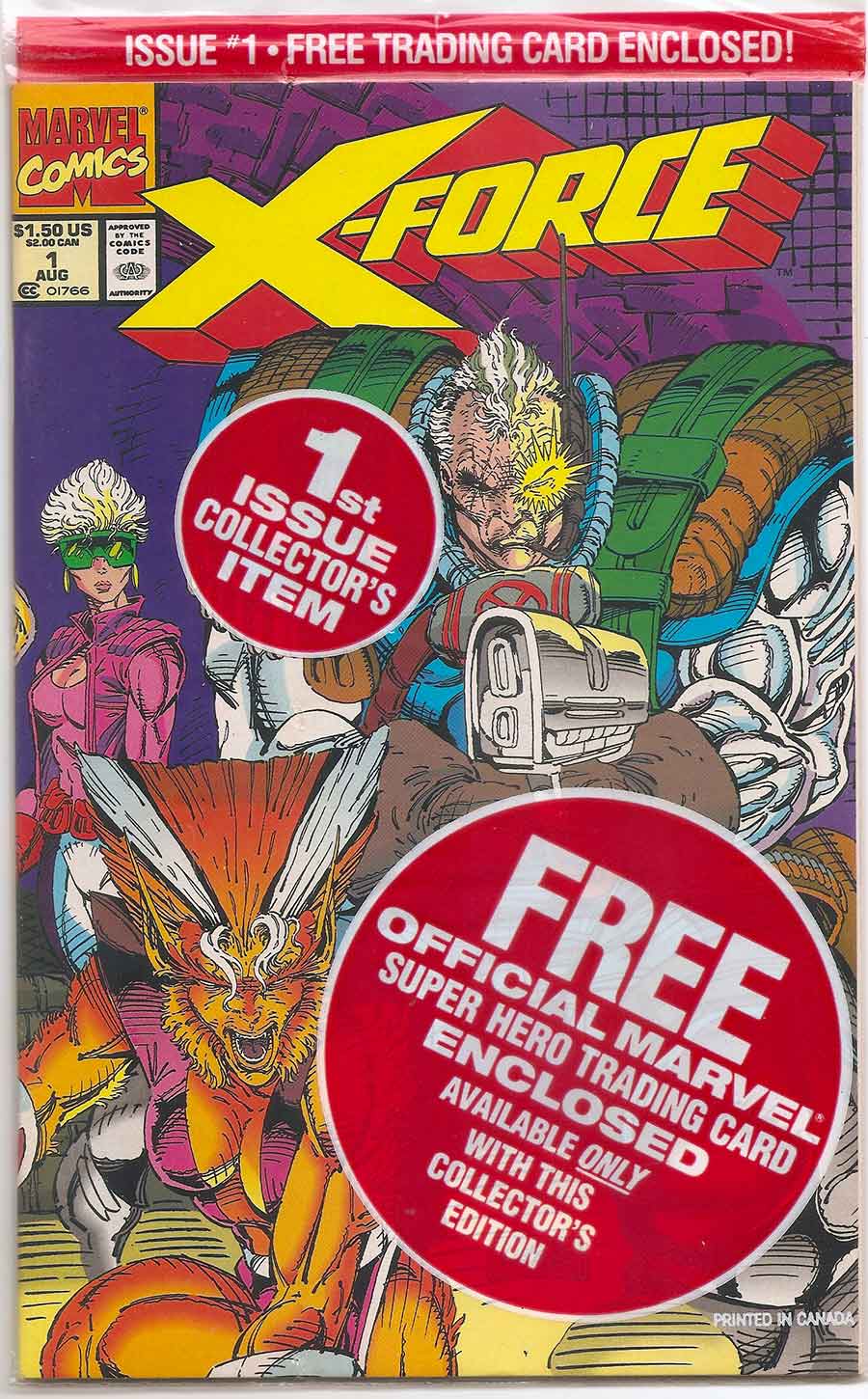

I recently filmed an unboxing video 17 on Instagram Live, in which I opened two five pound mystery boxes I bought from Mile High Comics. One was filled with Marvel releases and the other was all “dollar bin” comics, with the contents of each being completely unknown. While I did that because I thought it would be entertaining, 18 it ended up being surprisingly enlightening.

Within these boxes, 19 I came across a deluge of #1 issues from the past 40 years of comics, including notable titles like Rob Liefeld and Fabian Nicieza’s X-Force #1, complete with its polybag and trading cards. That comic was once a treasure, a desired release that sold millions out of hopes that it would someday make a person rich. Three decades later, it was just another comic in a mystery box, with little differentiating it from the bevy of forgettable titles surrounding it.

I love single issue comics, but it’s hard to deny that the majority of them are disposable beyond any personal reverence you hold towards them. There’s little worth there outside of certain exceptions, and because the typical, newly adult consumer doesn’t value the format in the same way, its potency is only degrading with time. That’s a problem.

When you combine that with consumer trends fueled by the pandemic, like how consumer behavior is shifting even more towards online shopping, per a research paper from consulting firm McKinsey (and reported by CNN), it’s hard not to see a greater shift towards digital for some single issues as anything but a reasonable, responsible thing. The key of course is trying to find a balance, and something that works for all players in the game: readers and collectors, publishers and retailers.

If you asked me last Thursday to pick the most likely scenario from the five, it would have been the first one if only because the direct market side of the industry abhors change. Of course, since then, business as usual changed completely, so there you go. But if I had to pick the one that would have the highest potential ceiling for all players, it’d be scenario four and its usage of digital as a low-cost onboarding option for new readers, a Black Label-like product for those who are both readers and collectors, and a blend of original graphic novels and hardcovers for those who prefer collections. I love that mix. That just feels like it has the greatest long-term potential, even if the energy coming off the furious posts rejecting that playbook on retailer forums would be enough to power the world for months.

Maybe that means the real answer will be somewhere in the middle. Maybe scenarios two or three is the play as an acquiescence between retailers and publishers. Or maybe DC’s move away from Diamond has triggered the direct market’s end times, 20 as laid out in scenario five. More than likely, it’ll be some combination of all of them. It’s hard to guess what the long-term future brings, as at this rate, it’s impossible to envision what tomorrow will bring for the world, let alone five years from now.

I will say this, though. Before the pandemic, I was about as big of an advocate for retailers as you could find. 21 In almost any situation where publishers and retailers were in opposition, I’d take the latter’s side. Since then, though, I’ve felt myself shifting with every vitriolic post slamming and denying alternative solutions each and every time they come up. Some retailers are advocating for just going with what worked yesterday when thinking of the solutions for tomorrow. After all, that’s the way it has always worked. Why change things when you know what you have already gets the job done?

It’s simple: because yesterday isn’t tomorrow. Nor should it be. And maybe we’d all be a lot better off if we stopped pretending otherwise.

Header image is from Midtown Comics in Manhattan.

For those that don’t know, Sliding Doors is a rather delightful Gwyneth Paltrow-starring film from 1998 where we see how one woman’s life plays out in parallel timelines defined by whether she did or did not catch a train in time to find her boyfriend in bed with someone else. John Hannah is a wonder in it. Also, nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition.↩

Before we get into the specifics, I’m focusing on the direct market – or comic shops – and direct market publishers as I think it’s reasonably safe to assume that the book market and related publishers as well as digital/webcomics will either a) continue to be quite healthy or b) continue to grow. ↩

Obviously there are far more than that.↩

Or DCBS.↩

Or Midtown Comics.↩

I’m legitimately what one could consider a “younger” reader and I have Reed Richards’ hair.↩

God only knows nostalgia is one way we know content can thrive.↩

As of 2018, at least, and including the book market.↩

Which in this case mean s movement of readers from print to digital, an idea some comic shops deeply fear.↩

That’s mostly a Marvel problem, but they both do it more than everyone else so they get lumped in the same boat.↩

Again, with a few exceptions.↩

So the guy was a pretty heavy buyer of new comics.↩

Again, this does not include subscription services.↩

It was once suggested to me that this was the highest selling comic on ComiXology during the title’s early days by a not inconsiderable margin.↩

As well as other spin-off titles like DCeased Unkillables.↩

Maybe even more than they did about DC leaving Diamond!↩

I know, I know, unboxing videos are ridiculous. But it was actually a lot of fun!↩

Which it was.↩

Both of which were accurately described by someone as Mile High’s attempts to dispense with excess inventory.↩

I’ve heard some suggest this in recent days. I just don’t buy it.↩

I still am. It’s just less a bit less universal.↩