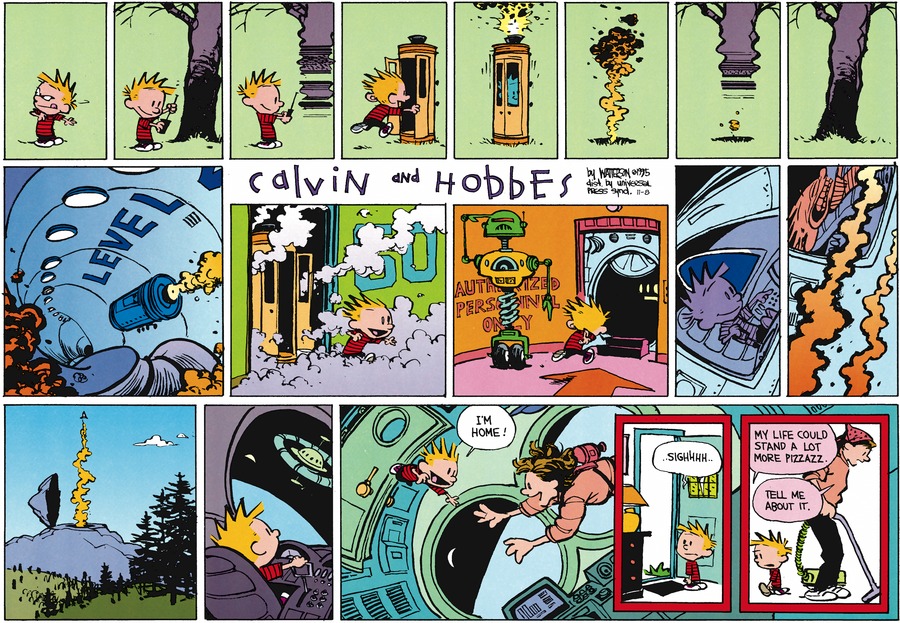

The Wonder and Legacy of Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes, Thirty Years Later

There’s something magical about being a kid. It’s a time of infinite opportunities. A time where pillows aren’t just pillows, but the key to a totally rad fort. The forest behind your house isn’t a weird wooded area your parents tell you to avoid, but a mystical land called “The Pond of the Sea Shaws.” That was my experience, and one many shared. As a kid, the world in front of you isn’t what you see; it’s everything you can imagine to be real.

That’s what Bill Watterson tapped into with Calvin and Hobbes, his beloved comic strip which debuted thirty years ago today in newspapers.

While I was but a wee child when it debuted – I was one and five sixths when the titular duo first greeted readers – it was a major influence in my life, and continues to be to this day.

You see, I was always a voracious reader. In elementary school, I was one of the rare students who joined the 500 Book Club, having read 500 books cover to cover by midway through fourth grade (there’s even a trophy to prove it). I enjoyed reading stories of all varieties, but comics made me love reading. And Calvin and Hobbes was one of my favorites. They’d often keep me company during Alaska’s cold winters, as Calvin and Hobbes weren’t just characters I enjoyed—they were friends.

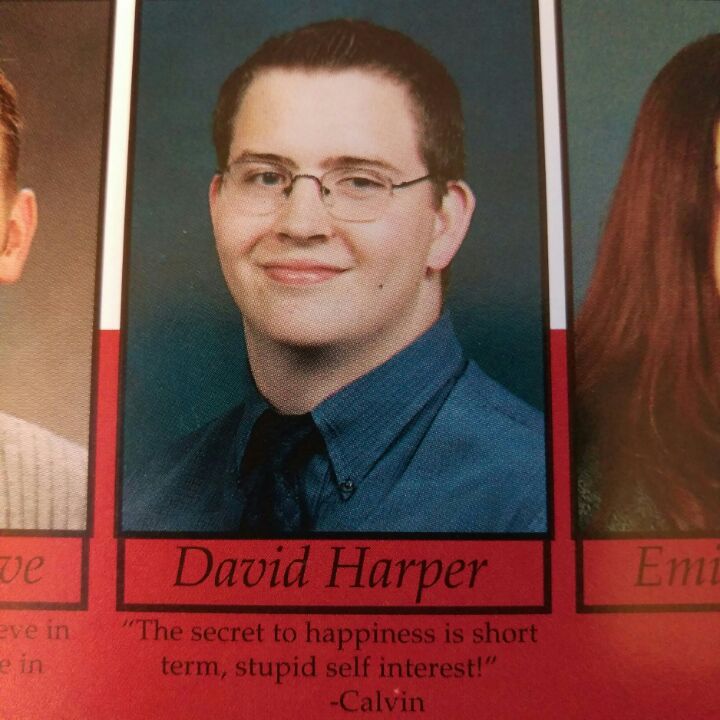

I still enjoy them to this day, although the gorgeous Complete Editions are less easy to read in your pajamas than the old softcovers I’d devour. The pair has carried with me throughout, and I commemorate them in small ways, whether that means my senior quote in my last high school yearbook (which you can see to the right) or the cover photo of my Twitter profile.

My love for reading has never passed, and it’s thanks to creations like the ones Watterson revealed thirty years ago. It’s not just me, though. Calvin and Hobbes is as beloved today as ever, despite being gone for almost twenty years. Why is that? And what makes it so special to people both young and old? I have my ideas, but let’s find out, shall we?

While Calvin and Hobbes is a comic you can enjoy at any point in your life – Watterson mined the same territory Pixar often does with work that amuses people of all ages – there was just something special about your earliest experiences with the comic. Age changes context for any form of entertainment, and what you love as a kid you often love in a different way as an adult, if at all. But when it gets down to it, there was something inexplicably great about Calvin and Hobbes that spoke to young people everywhere.

Skottie Young of I Hate Fairyland fame is onboard with that thought. While he can’t recall when he first read the strip, saying it “has been in (his) life for as long as (he) can remember,” he can trace his readership back to newspaper comic sections. As an actual paperboy during the time, Young shared he was “also kind of a Calvin and Hobbes dealer in a way.” That meant he brought joyous daily reads to plenty of kids (and adults) in his neighborhood.

“I can say why I love it now with great detail and attachment to all types of things, but back then I think I was just drawn to the cool spiky hair kid and his tiger pal that got into all types of trouble,” shared Young. “Calvin and Hobbes was just pure entertainment for me.”

Cartoonist Michael Cho (Shoplifter) first read Calvin and Hobbes early in his second decade. He was already a fan of comic strips, like the far more political and current event based Bloom County from Berkeley Breathed. That appreciation of the more experimental side of comic strips carried over to Watterson’s creation, but at first, he simply loved how weird, fun and and beautiful it was.

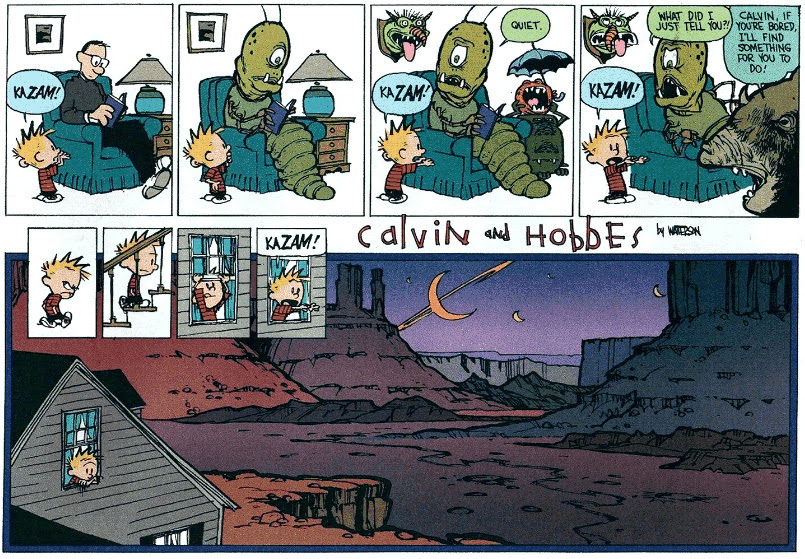

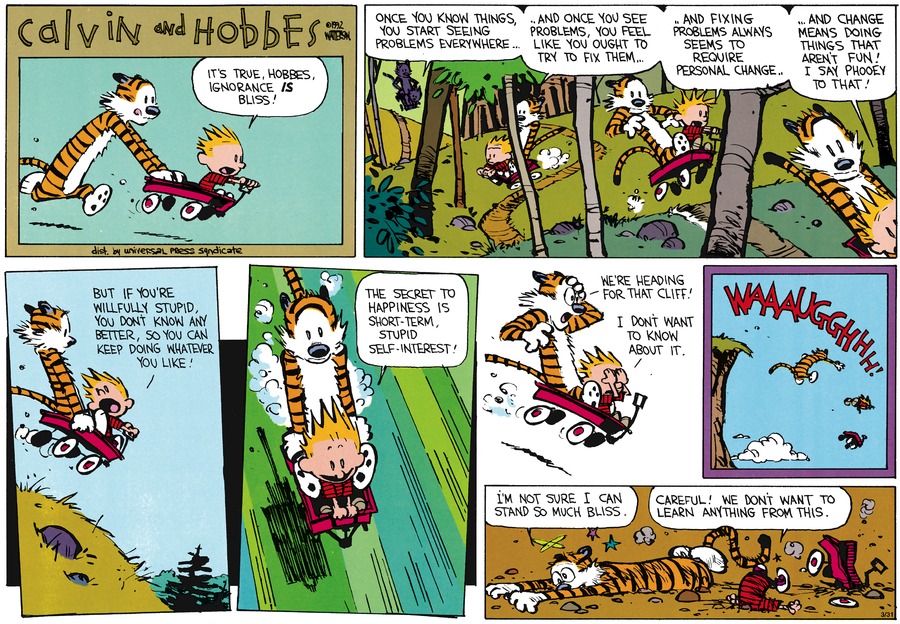

“Later, I’d recognize the humanity and warmth of the stories, but as a kid, I just loved the crazy trouble Calvin would get into. It was one of the few strips that I would genuinely laugh at,” Cho said. “And I always loved it when Watterson would break out his more naturalistic, ‘brushy style’ – the dinosaur-Calvin stories, the mimicking of ‘soap’ strip styles, etc.”

Amulet’s Kazu Kibuishi first jumped into the series sometime around high school, as his local paper didn’t run Calvin and Hobbes. It took a friend of his pointing it out for him to get onboard, and it was love at first sight.

“I was instantly a fan of the comic, and it was a big inspiration of mine as I went into college and continued drawing comics for the school newspaper,” shared Kibuishi.

For him, the art was a major factor. He was already in aspiring artist mode, and Watterson’s craft as a cartoonist and ability to tackle subjects and emotions of a wide variety was powerful for him as a reader.

“The art was always so great. The loose brush strokes implied a seriousness in craftsmanship that worked so well in contrast to the brash, hilarious jokes,” Kibuishi said. “The strip’s balance of humor, candor, and a yearning for romantic ideals was a potent combination for any young adult.”

Mark Tweedale is a columnist at Multiversity Comics, and you may know him as the guy who has forgotten more about Mike Mignola’s comics than anyone else has ever known. What you might not know is Calvin and Hobbes rivals even his love of the Mignolaverse, even if taking it in for the first time down in Australia was by accident.

“My parents never bought newspapers, and when I was thirteen, I was helping someone move. They were wrapping glasses and dishes in newspaper. Whenever I found a page of comic strips, I set them aside for reading when we were done,” he said. “So that’s where I discovered Calvin and Hobbes, and I bought Scientific Progress Goes ‘Boink’ as soon as I could afford it.”

For Tweedale, his love of the comic is personal. He sees a lot of himself in the strip, and it was very meaningful for him during an important time in his life.

“As a kid who spent a lot of my own childhood lost in fantasy worlds with imaginary friends (including a tiger), this clicked,” he said. “Hell, I even had my own version of Calvinball, which always seemed to involve climbing trees.”

He appreciated that Watterson always respected what it meant to be a kid, and that he never broke character, so to speak.

“Calvin and Hobbes remains the only story I’ve ever read that seems to genuinely respect a child’s imagination. When I see other stuff, the adult perspective seeps into it and poisons it. There’s that cloying aspect of, ‘Oh, aren’t children silly imagining they’re on a planet made of chocolate. They’ll believe any nonsense,’” Tweedale said. “Calvin’s worlds aren’t like that. They are vast and detailed and full of genuine peril. Calvin is totally invested and so are we as readers.”

That respect is enormous, as Young pointed out.

“When you’re a kid, you don’t feel like a kid. You feel like a person,” said Young. “Calvin and Hobbes felt the same.”

For kids both big and little, Calvin and Hobbes was a whole lot of things at once. It was an escape, and an entertaining one at that. It was a comic strip with art at another level than we had come to expect. The characters weren’t just kids; they were little people we could see ourselves in. Like my childhood journeys to the Pond of the Sea Shaws, Watterson created a world we could get lost in. All of that is why so many young readers find something to love in Calvin and Hobbes.

While many things you enjoyed as a child fall out of favor by the time you reach adulthood, Calvin and Hobbes is not one of them. Your enjoyment shifts, perspectives change and you notice things you never had before. For Chris Eliopoulos – who discovered it in his first semester of college – the way Watterson approached the comic was a game changer as he began his path towards being a cartoonist himself. The craftsmanship Watterson brought to the table wasn’t just impressive; it convinced him he needed to raise his own game.

“I grew up reading Peanuts and Pogo. I loved them. As I got older I started to see other strips that weren’t that well drawn. Bloom County came along and it was the first comic that I laughed out loud reading. I loved the writing. I also loved The Far Side for the writing. So I realized that the cartooning didn’t need to be great to have a good strip and I became lazy in my drawing thinking it was good enough,” he said. “Then I read Calvin and Hobbes and realized that if the art and writing were great, it was a whole other ball game.”

“He really opened my eyes to the potential of what a comic strip and a cartoonist could do,” Eliopoulos added. “He made me realize I needed to step up my game and get better.”

For the creators I spoke to – all artists – Watterson may not have been a direct influence, stylistically speaking, but the way he told a story left a mark on them. Kibuishi did pin Watterson as personally influential, and he feels Calvin and Hobbes was inspiring for many more people than just him.

“I think most young artists entering college must have been a huge fan of the comics, as they really reflected what it was like being a kid transitioning into the adult world while growing up in a generation where there was very little relative strife,” he said. “If Garfield can be seen as a reflection of the 70’s and 80’s Baby Boomers, then Calvin and Hobbes could be a reflection of the dreamers in Generations X and Y.”

The craftsmanship Watterson brought to the table impresses no matter your age. For a cartoonist like Jonathan Case (The New Deal), he loved the depth of Watterson’s cartooning.

“His characters, every one of them, are full of life and individuality, and they express themselves using every tool in the cartooning toolbox: from understated to bombastic, the people and creatures in Calvin and Hobbes are genuine and unique,” he said. “Beyond that, Watterson exhibited a top-tier level of creativity and skill in all parts of his work. The comic always felt fresh, even when it revisited stories and secondary characters like Calvin’s babysitter.”

“Watterson never gave less than everything to that comic, and he had a whole lot to give.”

“In terms of art, I was always aware that Watterson was a great draftsman. Under that deceptively simple exterior, you could always tell that the man knew how to DRAW,” shared Cho. “It came out in the foliage, the energy of his brush strokes, the colour pages in the collections.”

“I think a lot of people mistook his loose and masterful use of the brush and assumed that they could add the same energy to their work by being a little more heavy handed and sloppier with the brush,” he added. “But none of them could do what Watterson could.”

As Young aged, he dug into Watterson’s work more and more, attempting to deconstruct how the book turned out how it did. His experience became more studious, although it never ceased to bring the laughs.

“As a cartoonist, I read being the line and between the panels more than I would have as a kid,” he said. “I study it, trying to figure out Watterson’s thoughts while making it, or how he made it, etc.”

One of the most interesting things about how a reader’s Calvin and Hobbes experience changes with age is when the script gets flipped in terms of the characters they relate to. Growing up, we’re like Tweedale, seeing ourselves in the free spirit kid who is excited, awed and disgusted by the world all at the same time. But when you’re the parent who keeps getting killed in polls or has to cook the sentient dinner kids recoil from? That’s a whole different story.

“One thing that’s changed is that I feel more sympathy for Calvin’s mom and dad now and see Calvin through their eyes,” Cho said. “Comes with being a parent, I guess.”

“Now that I’m a dad, I do have a very different perspective when reading the comics and I definitely don’t identify with Calvin as much as I used to,” shared Kibuishi. “The shift in perspective has been very helpful when thinking about my own work.”

It’s a fascinating phenomenon, and one I can’t relate to as I don’t have kids. But it was an oft mentioned shift for the parents I spoke to. It shows how context can change a lot. However, it hardly impacts the love one has for Watterson’s creations.

The last point I wanted to bring up relates to a specific quote from Watterson’s interview with the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum’s Jenny Robb from Exploring Calvin and Hobbes. Robb put together one of the most robust interviews ever with the reclusive creator. In it, they tackled one of the reasons both teens and adults connect with the strip in a new way.

“I love the unpretentiousness of cartoons. If you sat down and wrote a two hundred page book called My Big Thoughts on Life, no one would read it,” said Watterson. “But if you stick those same thoughts in a comic strip and wrap them in a little joke that takes five seconds to read, now you’re talking to millions. Any writer would kill for that kind of audience. What a gift.”

Calvin and Hobbes, for all of its childlike glee and hilarity, was a comic that never shied away from bigger subjects and deeper lines of thinking. As Tweedale shared, “it’s this melancholy comic that wears its heart firmly on its sleeve.” In arcs like the one where Calvin and Hobbes discover an injured raccoon, Watterson explored meaningful subjects like life and death in impactful ways. It’s no coincidence Calvin and Hobbes were given the names of a theologian and a philosopher, respectively. Watterson wasn’t only interested in making people laugh; he wanted to make them think and feel.

He did, and he has for thirty years now.

You would never want to downplay Watterson’s artistry in determining why Calvin and Hobbes has had such a long and meaningful legacy. However, its creator’s choices outside the creative have helped it maintain its place as such a beloved strip after all of these years.

Like Kurt Cobain or James Dean, a creative spirit being extinguished before its perceived time is always a mournful thing. Watterson didn’t pass away, of course. But he chose to end the comic on his own terms, bringing the story to a close with one final strip on December 31, 1995. It was the right time, and it prevented Watterson’s creations from becoming something he didn’t want them to be.

“On purely artistic terms, I might argue that a comic strip, like anything else, has a natural life span,” said Watterson in the interview with Robb. “We all want to extend that life span, but after a point, the strip is on the machines and not breathing by itself anymore.”

Many strips and comics and narratives have done that. They lived on because of popularity, not because the creative drive was there any more. And without that drive, we – the readers – can see something has changed. Watterson bowing out before that became a thing helped turn Calvin and Hobbes into something transcendent. It’s something that shocked readers but, looking back, was important to its legacy.

“One thing I do know and have always appreciated is that he ended the strip on his terms and was willing to walk away from it instead of turning it into a giant licensing monster, with the work growing staler and more corporate as the profits increased,” said Cho. “As a teen, I was initially shocked and upset when it ended. But my friends and I debated it when it happened, and we all appreciated that he didn’t ‘sell out.’ That decision to end the strip was a big eye-opener for me and taught me that artistic integrity matters – even in the ‘funny papers.’

“I’ll always appreciate that lesson.”

Choosing his own end date helped ensure the strip never went through any lethargic stretches. As Kibuishi noted, Watterson displayed remarkable consistency in his ten years on Calvin and Hobbes. “You rarely felt that he created a filler comic strip,” Kibuishi said, and he’s right. Had he kept going, who knows if that would still be true?

When paired with Watterson’s steadfast decision to avoid licensing, Watterson’s early shuttering of the strip helped Calvin and Hobbes maintain a purity few comics can match. It was an enormous success, and Watterson’s earned enough from the strip to more or less never be heard from outside of his terms since. There was never a need to go back to the well as many other creators can’t resist doing. And he never leveraged his creations in a way that strayed from who they are. That kept them on a pedestal, and they’ve been there since.

Its timeless nature was paramount to its success as well. While many stories attempt to be more relatable by throwing in pop culture references, Watterson avoided that throughout. That means the book doesn’t move on as a relic of its time; it instead is as fresh and easy to connect to as the day it first arrived.

“The strip is timeless,” said Eliopoulos. “You read Bloom County today and you need to get the references. Not with Calvin and Hobbes. What the strip eventually became was a discovery of friendship and imagination and the realization that we all see our world differently. Those subjects are timeless.”

“I think his choice to not comment on current events or tie the ideas or thoughts to a year or era is what makes it timeless. Kids are timeless. There has been and always will be little kids who have (a) toy that they know is their friend,” shared Young. “The cartooning was also perfect in its ‘what year does this take place?’ (nature). A striped t-shirt will work forever. His house looks like it is old and brand new at the same time. Every choice he made allow(s) this strip to be relevant to whoever picks (it) up in whatever year.

“That’s an accomplishment.”

That’s why Young can share it’s something he and his kids can read together now and enjoy just the same. “In fact, we’re starting it for bedtime reading now!” he said.

He’s not the only one who had that experience, as Cho passed the collections onto his daughter.

“I’ve got a few collections that have survived since childhood – all with broken spines and dog-eared pages like any true totem. They were among the first comics I read to my daughter. I had to skip the more subtle gags, but she appreciated the manic ones right away,” he said. “She has the books in her room now, but they’re really falling apart.”

Above everything, though, the book has carried on from generation to generation because it was – and still is – one of the finest comics of any variety ever created. It may not be everyone’s favorite, but it’s a comic anyone can enjoy. That speaks to the gifts of Watterson, above all.

“Bill Watterson is an immensely talented cartoonist and writer, and I think the continued popularity of Calvin and Hobbes is a testament to his abilities and keen observations,” Kibuishi said. “I’m very glad the comics are still remembered and enjoyed by many readers today.”

Calvin and Hobbes continue to entertain, move, challenge, amuse and influence readers as much as they did when they first arrived on November 18, 1985. That means a lot, and it’s because Watterson valued them as more than just creations: he treated them as characters as real and tangible as the person holding the newspaper they were found in.

“The characters were very alive to me. I don’t know if this makes sense to people, but when you’re doing this right, you’re not putting words in the characters’ mouths,” Watterson said in the interview with Robb. “Instead, you’re listening to them. They talk on their own, and you just follow along behind. The characters write their own material. And that’s what happened—Calvin and Hobbes wrote their own material.”

Calvin and Hobbes may have ended twenty years ago this New Year’s Eve, but the story and its characters live on with every reader who sits down with them. The titular duo continues to explore this magical world, and if you’re willing to, you can go along with them on an adventure whenever you’d like. All you have to do is pick up a book. Do that, and they’re back.

Just like they never left.

All comic strips featured were created by Bill Watterson, with images taken from GoComics.com, © Universal Press Syndicate. Thanks to Jonathan Case, Michael Cho, Chris Eliopoulos, Kazu Kibuishi, Mark Tweedale and Skottie Young for the perspective for this piece.