Value Over Replacement Batman

Does Batman sell Batman? Or is it more complicated than that? Let’s find out, as we answer some good ol’ fashioned Bat-Questions.

When James Tynion IV announced he was leaving the cushest gig in superhero comics – writing Batman – to take his talents to Substack, there were a range of responses to this absolutely loaded concept. Questions about Substack and Tynion’s focus on creator-owned works were pervasive, amongst others. But the dominant angle wasn’t about where Tynion was headed; it connected to what he was leaving. Headlines almost always said something like, “James Tynion Quits Batman” or “James Tynion Leaves Batman,” as if it was a marriage rather than a for-hire job. That’s understandable. Batman is a big deal!

That ultimately led to another recurring idea, which was something like, “DC’s going to have a tough time replacing Tynion on Batman.” The writer’s run was notable for reigniting heat on the title after it aged in the post-Rebirth era, introducing a deluge of new characters and surrounding energy to the series. That type of inventiveness hadn’t been seen on the title for a bit, save for a Court of Owls here or a Duke Thomas there. There was a juice Tynion brought to Batman that was refreshing for readers and retailers, attracting interested parties of all varieties in the process. 1

That idea was always a bit confounding to me, though. Not because I don’t think highly of Tynion’s work. It’s just in my mind, there’s one thing that sells Batman comics above all: The Dark Knight himself. All you have to do is swing by a movie theater or a big box store to see that people absolutely love the character. That is, if you needed a reminder, because he’s going on multiple decades of pop culture dominance. Tynion is great. But Batman is Batman. The series would be fine. It would continue to sell, no matter who took over writing it. 2

Or at least so I thought. Maybe I was wrong! Maybe this was one of those theories that was as fictional as the character himself. Sure, I had conversations with people about the very idea, even previous writers of the title, in which they echoed my sentiment. But that hardly verified it. I mean, it would hardly be the first time that multiple people shared an incorrect hypothesis. So, who was right? Does Batman sell Batman, or is it more complicated than that? The good news is, there was a way for me to answer this question: by diving into sales data.

That’s exactly what happened recently, as I tracked and charted 25 years of single-issue orders for Batman 3 from comic shops 4 as well as the creators involved to see if there is a notable impact from those who work on it, and when that tends to happen. And let me tell you, I went into this exercise expecting one thing. I came out having learned a lot more than I could have predicted. Today, we’ll be breaking down those learnings by answering eight questions related to the subject, and it all starts with the creation of a new statistic to better answer the question that inspired all of this.

1. Does my theory that Batman is what sells Batman stand up to analysis?

After breaking down 25 years of sales data, it’s clear that Batman’s floor for comic shop orders is solid – although considerably lower than many of you might imagine, as we’ll cover soon – and its ceiling is very high. Batman will always be Batman, which means Batman will always sell comic books. The character undoubtedly establishes the sales floor for the title, with that baseline shifting from time to time due to larger comic industry or publisher trends.

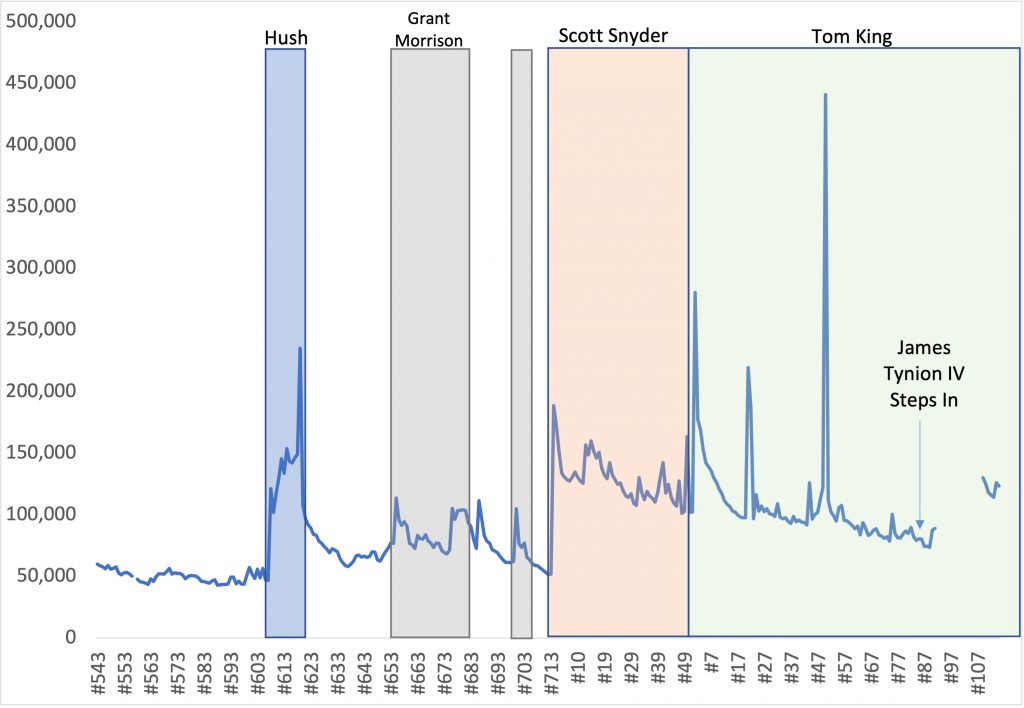

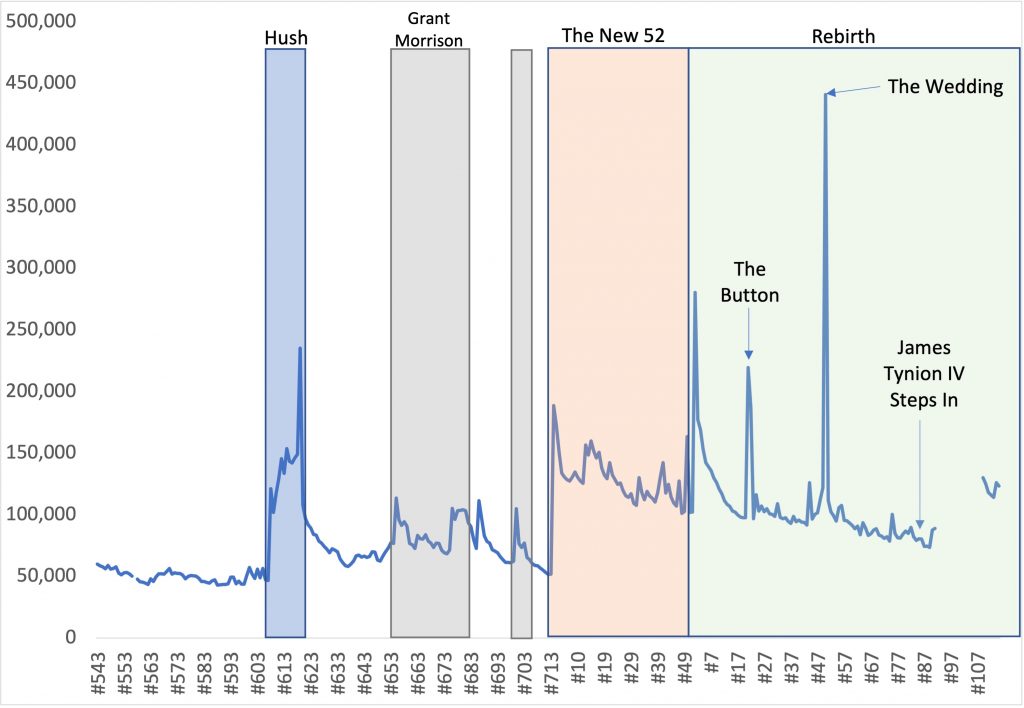

The ceiling, on the other hand, can be greatly affected by the creators who work on the book. But that is not always the case. During those 25 years, 29 different writers wrote at least one issue of Batman. Most of them had no obvious impact on orders from comic shops. Some did, though! Here’s a quick chart showcasing those that clearly had some level of influence.

Some of those periods of growth are complicated by other factors. We’ll get into that. But each passes the eye test with flying colors. Even without numbers or more extensive analysis, it’s easy to see that when these five writers or creative teams – Jeph Loeb and Jim Lee when they parachuted in for Hush, Grant Morrison on their extensive and occasionally splintered run on the main book, Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo’s 52 issue journey, Tom King’s period filled with explosive highs, and Tynion’s recent takeover – signed up on Batman, comic shops changed their ordering habits on the title. How much they impacted the title depended on the team.

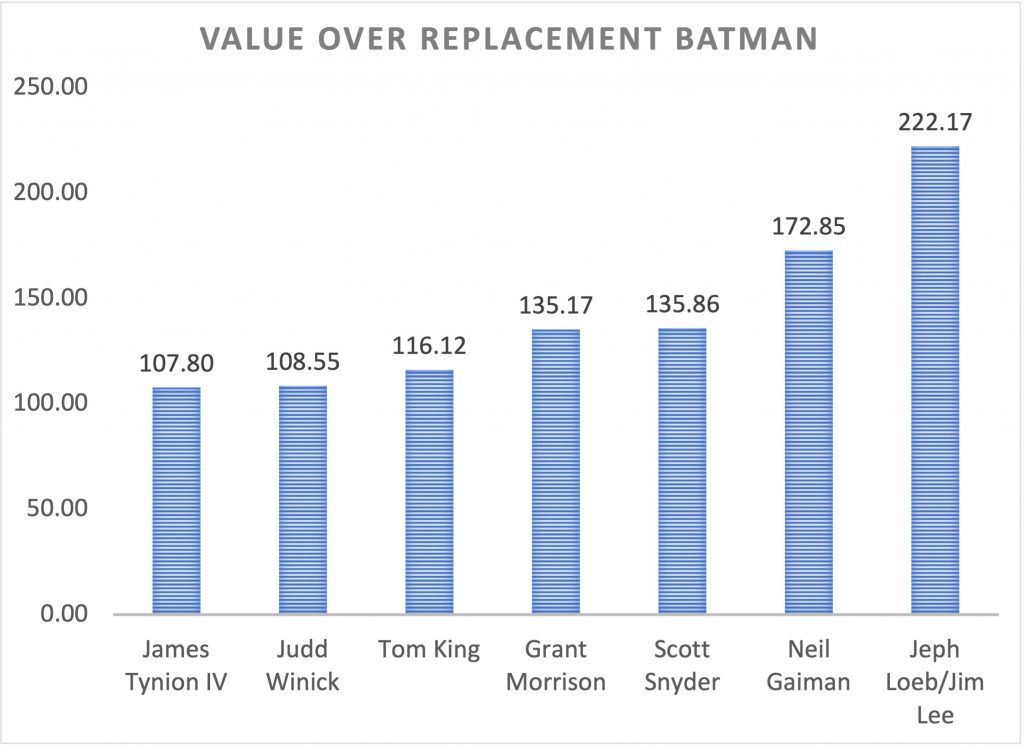

To help better express that, I created a statistic I’m calling Value Over Replacement Batman, or VORB. This might sound like the set up for a good Jean-Paul Valley joke, but that’s not the case. It’s just a way to easier highlight the impact writers and creative teams had on the title’s sales relative to a baseline.

The simplest explanation of this stat is as follows. Every writer who wrote five or fewer issues of Batman was grouped into a bucket I called “Replacement Batman,” with that forming the baseline average — or replacement level — of sales for the title, represented by the number 100. Everyone who tackled six issues or more during that span was averaged out, divided by that “Replacement Batman” level, and then framed relative to 100 as the average. This results in a situation where 110 would be ten percent higher than average, 150 would be 50 percent higher, 90 would be 10 percent lower, etc. etc. Each writer/creative team was positioned against the era it existed within 5 to help normalize for the relevant status quo. The higher the VORB, the greater the impact. Got it?

Here’s that chart, focusing only on those with an above replacement level VORB.

There were a total of seven writers or creative teams that finished with an above replacement VORB. Two we’ll talk about quickly, just to move on from. Judd Winick was a bit of an outlier, as he was a pinch hitter of sorts who stepped in for an arc at a time in-between notable runs. That’s not to say he didn’t do good work. It’s just his efforts were often the comedown in terms of orders, not the come up.

Neil Gaiman is a cheat, as he only wrote one issue, but it was one I wanted to highlight. It was #686, the “final” issue of Batman for a staggering four months, 6 and the first part of a two-part story, “Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader?” told in Batman and Detective Comics with artist Andy Kubert. It was a giant seller, especially compared to others from the era. A lot of that was the “final” issue angle. But Gaiman clearly had an impact, if only because it triggered such an unusual spike in sales — especially compared to that volume’s actual last issue just 27 issues later, which sold fewer than half the copies. Gaiman’s single appearance on the title moved the needle quite a bit, and is evidence of the impact creators can have. 7

One creative team led the pack by a mile. The Hush team of Jeph Loeb and Jim Lee had the biggest impact, as their run had a VORB that was a staggering 122% above replacement. It couldn’t have come at a better time either. While talented folks were working on the series before them, Batman was at a nadir in terms of orders. The month before Lee and Loeb joined up, the title was the 32nd most ordered comic in the market. It immediately jumped to the top spot with those two on board, building and building before peaking in orders with their final issue, a rarity in the direct market. As soon as they left, orders dropped by more than half. But their area of effect was significant, as the post-Hush period was considerably stronger than the one that preceded it. Lee and Loeb effectively resurrected the series during a rather dark patch.

Everyone else on this list had some sort of impact, although some with more noise surrounding the sales than others. But I want to tout Morrison in particular, as their run is the second most inarguable in terms of influencing sales. That VORB of 135 only places Morrison fourth, but it came after the title was starting to dip again, post-Hush. Morrison’s efforts dragged the series out of a period of listlessness, with the writer’s first issue bumping the title from 26th on the charts to 5th. The overall impact Morrison had on the character is hardly even felt with these numbers, as they wrote the character on other top sellers like Batman & Robin and Batman: The Return of Bruce Wayne. Morrison was both a defining voice on the title and a real driver of sales.

Let’s go back to the question at hand, though. Does my theory that Batman is what drives sales rather than creators stand up to analysis? Batman is a huge part of the formula, but no. Creators do have a significant impact, and it’s one that’s mostly evident on the high end. It’s easier to sell because it’s Batman, but if you put, say, me on Batman, its orders would drop considerably immediately.

Thankfully, DC is better at hiring than that.

2. Which creator had the biggest impact on Batman sales in the past 25 years?

When looking through the numbers, it’s apparent that writers have a more consistent impact on Batman’s fortunes than artists. That’s at least in part because of the system in place and the nature of the roles. Writers stick around for longer while artists rotate. But it’s still true…for the most part. That said, if I had to pick the creator whose presence had the biggest impact on orders on Batman over the past 25 years, it’s an easy answer. It has to be one of the two members of the Hush team.

With apologies to the retailer who suggested via text that Loeb – who was very hot at the time and had just written Batman: The Long Halloween, one of the most beloved Batman titles ever, half a decade before – and his influence cannot be ignored, Jim Lee is the biggest exception to that writer-centric rule of Batman. Lee was arguably the most popular artist in comics at the time and was tackling his first extended run on the character. Upon his arrival, the title immediately went from the relative doldrums to the hottest series in comics. I’d say Lee’s impact was the most significant of any creator on Batman in the past quarter century, with a nod of respect towards Loeb for his contributions.

3. Where can you really see the impact of creators on sales?

Hitting massive sales numbers is important. Creators play a big part in that, as I noted. But sustainability matters too. I’ve talked with people from publishers about how the real impact creative teams have on sales isn’t necessarily at launch, but in how orders hold up. Attrition is the real nightmare for ongoing comics. After all, every publisher knows how to launch a book. 8 Keeping readers is the tough part. Predictable drops are always built into sales forecast for a title. If those can be mitigated, then that’s the creators connecting with fans in a real way.

Lee and Loeb’s work on Hush was the dream experience, the rarest of all comic book flowers. Orders didn’t just maintain when they were on the title; they increased. That’s incredible. Two others stood out in this regard, even if orders did not increase for them typically. One was Morrison, whose run had the orders with the lowest standard deviation over the 25 year span. 9 While they weren’t a constant — because no title’s sales are — they were the closest to achieving that of anyone besides Lee and Loeb.

The other was Snyder and Capullo, who had the second lowest standard deviation. This is another place where the artist likely mattered. Capullo joined Snyder on the second volume of Batman, with Snyder writing 52 of its 53 issues and Capullo drawing 46 of those 52, an incredible feat. It wasn’t just the Scott Snyder show, but Snyder and Capullo. No other stretch from a writer/artist combo on Batman can compare to that consistency. That reliability was massive, with the duo being the hottest team on the title over the past decade at least in part because of how predictable the team was. The numbers backed that up, just as they back up how creators can limit dramatic downturns in orders from shops.

4. Did James Tynion in specific seem to have an impact on Batman’s sales? Also known as, was I wrong?!

As much as it pains me to admit it, my completely made-up statistic is imperfect. VORB likely underrates one person above all, and that’s Tynion. That’s not VORB’s fault, though. It’s because of the data. For the majority of Tynion’s run, order numbers either a) completely disappeared because of the pandemic and DC’s move from Diamond Comic Distributors to Lunar Distribution or b) have estimates that don’t totally pass the smell test, according to people I’ve talked to at DC. 10 That makes judging his run tricky. The data is all over the place. Tynion’s run had steady estimates for six issues, nothing for 17, perhaps soft estimates for seven, and then nothing again for his last two. It’s a tough stretch to analyze for that reason.

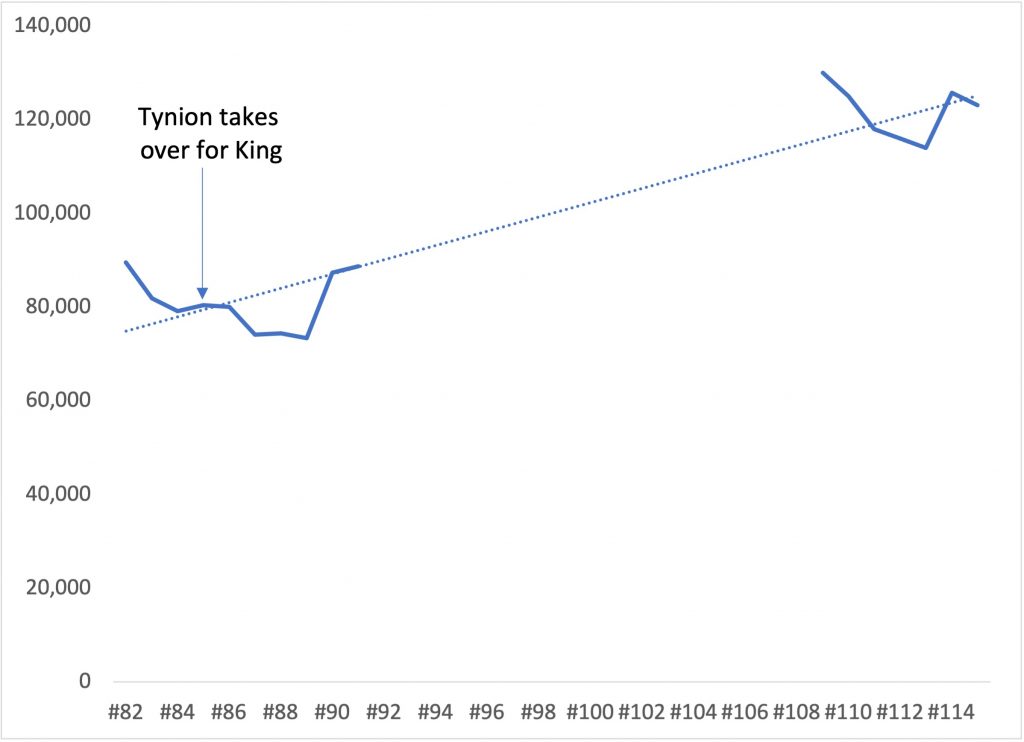

So we’re going to have to make some estimates of our own based off what we can see, making educated guesses from available sales data. Here’s a chart of Tynion’s run and where the book was before he took over, with a trendline worked in to highlight the arc of sales during the gap in estimates.

Again, the pandemic gap makes it impossible for us to say exactly what impact Tynion had on Batman’s sales. It’s the most apples-to-oranges period to judge because of that. But looking at where he started, the direction they were headed once Tynion started making his presence felt, 11 and where the title was once numbers picked back up, it’s apparent that Tynion had a very positive influence, even if that trendline is a rather imperfect illustration of what the numbers likely looked like. But the gap between where sales were when the pandemic hit and when estimates returned is gigantic. The eye test says Tynion had a major impact. Conversations I’ve had back that up. We just don’t have numbers to prove it.

And one thing that makes Tynion’s stretch interesting to me is that it was the first time in the past ten years that someone took over Batman for a sustained run without it relaunching with a new #1. Not having line-wide decision making influencing its sales makes the creative team’s influence more obvious. 12 It’s clear that Batman saw serious lift because of the efforts of Tynion and the artists on the book, like Jorge Jimenez, Guillem March, and beyond, just as it’s clear that creators can have an impact.

That said, Tynion’s success does not prohibit success from the creators that followed, especially with Jimenez being a constant on the book. We have no insight into overall orders on writer Joshua Williamson’s follow-up efforts, but thanks to ComicHub’s sell-through data on ICv2, we do know that it’s maintained its position as a top four seller at a minimum. 13 That’s pretty good! I’m going to call my assertion half-correct, as Batman seems fine in the post-Tynion era, but the writer did have a substantial impact. Everyone wins!

5. Has anything had a bigger impact than the creators onboard or the character himself?

Back in the first point, I said that some of the periods of growth were complicated by other factors. Here’s a new version of that chart with notes modified to reveal what those other factors were.

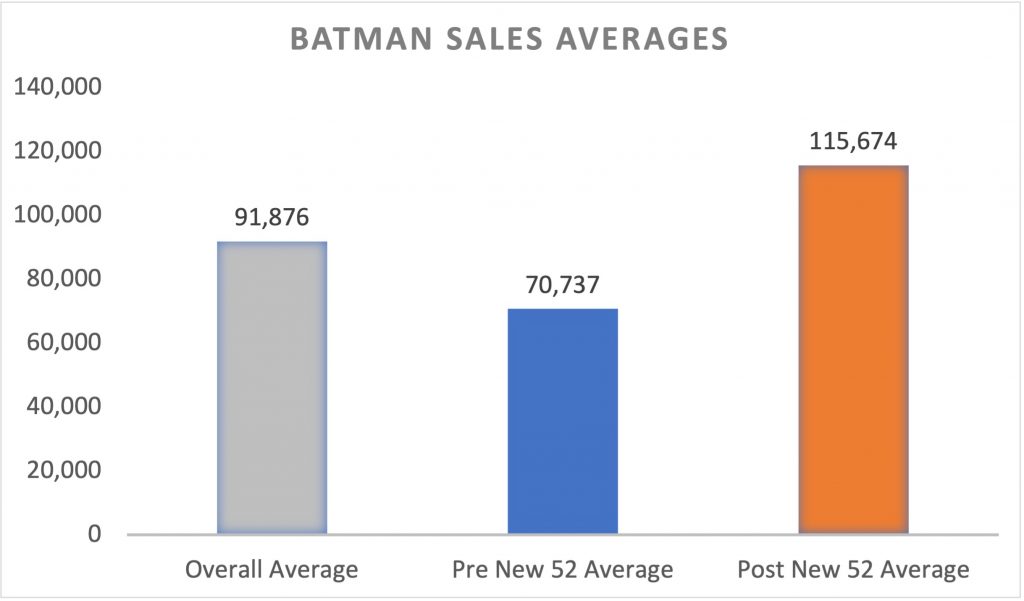

I’m not saying this to diminish the work of Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo or Tom King, but the biggest influence on the sales of their runs – at least initially – were the relaunches they were a part of. The New 52 and Rebirth fueled the growth of Batman more than any single creator over that stretch, which we know because every DC title was affected in a similar way initially. Here’s another chart to quickly emphasize that impact.

The average orders of Batman since The New 52 hit have been 63.53% higher than before the relaunch, a staggering number. That’s complicated by other surrounding factors, of course. Even beyond the creative team’s impact, the 14 years before The New 52 include some of the most fallow years in the history of the direct market, so it’s an unnatural high compared to a natural low. But DC’s famed relaunch was a significant part of the reason the entire industry saw a spike afterwards, not just Batman as a title. And it’s easy to see in the numbers that despite our admonishments, these relaunches work – or worked at the very least – as a quick comparison of the final ten issues of Batman during The New 52 and the first ten during Rebirth saw an increase in orders of 36.31% favoring the latter. Relaunches can be CPR on a dying patient, even if that was hardly the case at the end of Snyder and Capullo’s run. 14

These relaunches had an impact that almost no creators could possibly match, especially The New 52. That endeavor had an immense amount of advertising money behind it and media coverage around it because of its singular, unexpected nature. You only have one first relaunch, and DC played that one right, at least from a promotional standpoint. It was a monster. Snyder and Capullo did maintain those sales, which is a massive feather in their cap, as we discussed earlier. But they were put in a position to do so thanks to this relaunch.

Relaunches aren’t the only element outside of creators that can inspire a deluge of orders, either. Much hyped stories can have a similar impact, even if it’s considerably briefer. During King’s run, there were two issues that showcase this by breaking every trend line, which you can see as two significant spikes during the Rebirth era. Those were #21 – the first issue of the Batman/The Flash crossover “The Button” that was effectively hyped as a Watchmen story – and #50, the Batman/Catwoman wedding that didn’t happen. Those boosted orders are so short-lived and anomalous compared to the rest that it’s clear they’re outliers, albeit outliers written by King, just like the rest. At the very least, they are visual evidence as to why superhero stories have always loved a good wedding: they sell quite nicely.

Lastly, it’s worth noting that while creators have an impact, they’re also subject to the whims of the industry in the moment. Sometimes that’s good, like Tynion’s run coinciding with a collector boom during the pandemic. Sometimes that’s bad, like in the late 1990s and early 2000s when the direct market was struggling. All the good and all of the bad can’t be put on one or two names alone, because there’s other factors in play.

6. Does all of this noise make it difficult to make assertions about anything based on sales data alone?

Absolutely! Anyone who suggests otherwise is trying to use data sell their point or to make a bunch of nonsense up. Orders from shops are not influenced by any single factor, so to say with certainty that sales were up because of a single creator or down because a decision about a character or whatever is simply unearned bravado.

Sales data is clear, but the story behind it is anything but. There’s a ton of noise in the reasoning for the total order numbers for every issue of every volume of Batman, or really every volume of every comic ever. Don’t ever let anyone tell you otherwise — unless that person is me!

7. Has Batman always been a dominant title in the direct market?

Nope! Batman itself wasn’t always Batman, at least relative to sales expectations. We think of the title today as the constant of the industry, the infallible titan from which all other titles are judged. 15 This was not always the case. It was outside the top ten of orders for the bulk of the early years of my research.

Granted, the late 1990s and early 2000s was a wildly different time for the industry. It was a low point for direct market orders overall. 16 But as noted before, the last issue before Jeph Loeb and Jim Lee took over charted at #32, 17 an unthinkable number in 2022. Sure, Batman’s low point in sales was a symptom of the direct market’s weakened performance, with Lee and Loeb acting as the cure. But as much as I believed that Batman was always and always will be a dominant force in the direct market, it just isn’t true.

8. Were there any surprising takeaways from this research?

Yep! One was obvious from the start. People complain all the time about the number of Batman titles today, and sure, there are a ton. But this is hardly new. Even when sales were a fraction of what they are today, Batman was carrying double digit titles in DC’s line. The first month I charted — April 1997 — saw Batman with fewer than 60,000 copies ordered and 11 associated titles, or 12 if you include Dark Claw Adventures. 18 DC has always rolled deep with the character.

One other thing stood out about Batman in specific: longevity matters. While popular creators have an outsized impact, if they constantly rotate on and off the series, their impact can be mitigated. You can see that especially during Morrison’s run, where writers like John Ostrander and Tony S. Daniel pop in for an arc or two. By the time Morrison returned, the title had to rebuild from a slight deficit. Their time on the title was the most broken up, at least in part because the writer handled multiple Batman titles during that stretch. The runs with the highest VORB were typically the ones with the most prolonged uninterrupted stretches.

You could argue that they were consistent runs because their sales were also consistent, making this a bit of a chicken and the egg type situation. But early on in my look at these numbers, creative teams rotated off the title at a velocity that made it impossible to figure out if they had any impact at all. While creative consistency on Batman is shockingly uniform these days, that wasn’t always a hallmark of the title. Back in the late 1990s, there was an eight issue stretch in which seven different writers worked on the book. It was during a time that the most consecutive issues someone wrote was seven, with the title featuring a wild mix of talent throughout that stretch. 19 During that period of constant change, Batman sales hit a nadir. That feels related, even if it was during a nightmare stretch for the direct market, which likely had a massive impact as well.

There can be diminishing returns to longevity. Looking at the numbers and considering how it ended, you could suggest that King outstayed his welcome on the title in the eyes of readers and retailers. His run’s orders easily had the highest standard deviation of the top names — undoubtedly fueled in part by the wedding issue being such an anomaly in terms of orders — and was lagging in sales towards its conclusion. 85 issues is a lot in this era of comics. There can be a Harvey Dent in The Dark Knight-like feel to this trend, as creators on Batman tend to leave the book a hero or stay on it long enough to become the villain. But there does seem to be value in getting to dig into your story enough for word of mouth to spread and FOMO to sink in. That’s difficult to do without having a decent sized run on a series. 20

Lastly, going through this effort reminded me of just how much of a copycat industry the direct market really is. I know that’s a real Captain Obvious assertion, but it’s true. Every time something generated a modicum of success – relaunches, renumberings, inclusions in a Loot Crate, 21 certain cover trends – publishers, but particularly Marvel and DC, would milk whichever concept hit until it was no longer viable. It’s understandable, of course. Following trends can generate big results.

But if there’s one thing I learned from this exercise, it’s that a concept or a gimmick can sell a comic for a time, but the best way to keep selling them is to hire exceptional talent and give them the rope to do something great. Or just have a wedding every issue! One of the two.

Fun fact: Speculators love first appearances.↩

That they got Joshua Williamson and then Chip Zdarsky made it even more certain.↩

The title, not the character.↩

Via Comichron, John Jackson Miller’s invaluable resource of direct market sales from throughout the years. It is the best.↩

Meaning pre-New 52 and post, as those are rather different periods. We’ll go over that in a second↩

Shouts to DC for pretending like Batman was both dead – this was around Final Crisis – and no longer a series. I would describe this effort as moderately convincing.↩

Kubert probably played a role here too.↩

Today’s formula is sprinkle a bunch of variants on, add returnability, hype it up to retailers, and then watch the magic happen.↩

A standard deviation is, “a measure of how dispersed the data is in relation to the mean.” Or, basically, how much variation there is in a set of numbers, which helps us gauge consistency.↩

Miller is doing a great job making a tough situation work, but it’s been suggested to me that order numbers for DC’s top titles have been underestimated.↩

Its rise was beginning right before the pandemic.↩

This stretch did come during a boom time where per title sales unexpectedly rose industry wide because of shifts in consumer behavior during the pandemic and because of a reduction in the total titles published, though.↩

At least in the 100 or so shops that use ComicHub.↩

They were still going strong.↩

While DC was at Diamond, this was literally true. Batman formed the baseline of sales estimates from Diamond, sort of like VORB but for the whole industry.↩

Here’s a chart tracking overall industry unit sales in the top 300 over the past 25 years. You can see just how low things got during that stretch.↩

Behind titles like Green Arrow, G.I. Joe, and an Image release called Battle of the Planets!↩

Incredibly, that title and Batman vs. Aliens #2 were the top two sellers from the line that month. Batman vs. Aliens!↩

For example: during one five issue period in 2001, Greg Rucka, Brian K. Vaughan, and Ed Brubaker each wrote at least one issue. This was before they were the household names they are today in comics, though.↩

Unless you’re Neil Gaiman.↩

The weirdest fact from the last six years of comics might be that Big Trouble in Little China/Escape from New York #1 was the most ordered comic of 2016, simply because it was included in a Loot Crate.↩