On The Walking Dead #193 and Finding Your Own Way Out

I take a look at how The Walking Dead ended through the prism of how it lived

This is a look at The Walking Dead #193, and while it’s not focused on plot, spoilers from The Walking Dead #192 and #193 are discussed within. So…beware.

When any series is beginning, ending or going through even a minor change, the common plan in comics marketing is to act as if said shift is going to be the biggest thing we’ve ever seen. My inbox is often flush with marketing and PR emails stating how some such comic is going to have an “epic” finale or an “unforgettable” debut or, more often than not, some sort of moment that will change the comic forever. It can feel like marketing mad libs, making for easy to forget comics even as I’m implored to believe that this will be quite impossible to do.

Of course, when we’re talking about endings in particular, there’s always a certain level of anticipation that comes with those when it involves a long-running story. Look at Game of Thrones and its eighth and final season. That was arguably the most anticipated pop culture event of…I don’t know, this century? And with great hype levels come great speculation. Everyone had an idea as to what would happen, who would die and how it would all end, whether you’re talking about the cook at your favorite local diner or the person who works at your dry cleaners.

It became so all-encompassing that fan speculation was almost treated like text, and when the text itself – the show – was revealed, it was judged against the idea of what it should be rather than it was at times. Say what you will about the season’s quality, which was at times as good as ever and at other times filled with maddening decisions from a writing standpoint, but it often felt like the narrative that surrounded the “quality” of the series wasn’t even about what happened on the screen as much as it was about what didn’t happen.

That’s what happens with build up, though. Whether it’s a debut, finale or game changing event in the middle of a story, when given time, fans will create a narrative for themselves that any story will struggle to match up against. Fair or unfair, that’s the reality of narrative storytelling in 2019.

That’s why I respect the hell out of Robert Kirkman’s decision to end the long-running comic series The Walking Dead completely out of nowhere with its 193rd issue. If we were told resolutely “this comic will end with issue #200” or some number of that sort, an array of comic sites would turn its three month window into a cottage industry of unfounded speculation posts. “Did this gesture by Jesus in issue #181 indicate that The Governor was never actually dead?” Spoiler alert: it didn’t, and no one in the world will ever, ever need that kind of content. By stealth concluding this series, Kirkman and his collaborators in line artist Charlie Adlard, gray tones artist Cliff Rathburn and letterer Rus Wooton skipped past go and let the text speak for itself.

And I loved it, if only for that reason.

But I loved it for more than just that, and a big part of the reason is because of how well it fit everything that preceded this finale. Say what you will about the series qualitatively – it had become in vogue to hate on it despite having zero drop off from its historical average, and that likely has more to do with perceptions of its success than actual quality – but it has long been one that marched to the beat of its own drummer, with a lifespan that is fundamentally impossible to recreate for any series. I mean, think about where it came from and what it became. Let’s break it down:

- Launched by Kirkman and original series artist Tony Moore as the 233rd most ordered series of October 2003, falling behind not just the main Sam & Twitch series but the prodigal Spawn police duo’s second title

- Grinded its way to success on the strength of high selling trade paperbacks – the format I was introduced to the series through – which led to Kirkman becoming an Image partner in 2008

- Managed to pull off the rare double feature of winning the Best Continuing Series Eisner Award and launching a soon-to-be mega popular television series in 2010

- Rolled out another unique pairing, as it was the most ordered comic and most watched cable television show in October of 2014

Not only that, but it was the comic that sparked a revolution for Image Comics, as Kirkman – long an outspoken advocate for creator-owned comics, as his famed Kirkman Manifesto implored fellow notable creators to not grind through for-hire work writing and drawing characters someone else owned when they could tell stories with characters they owned – and The Walking Dead acted almost as proof of concept for the company’s entire platform. “Look at The Walking Dead,” the publisher could say. “Come to us, and your next comic could be the next giant hit both in comics and in other mediums.” 1

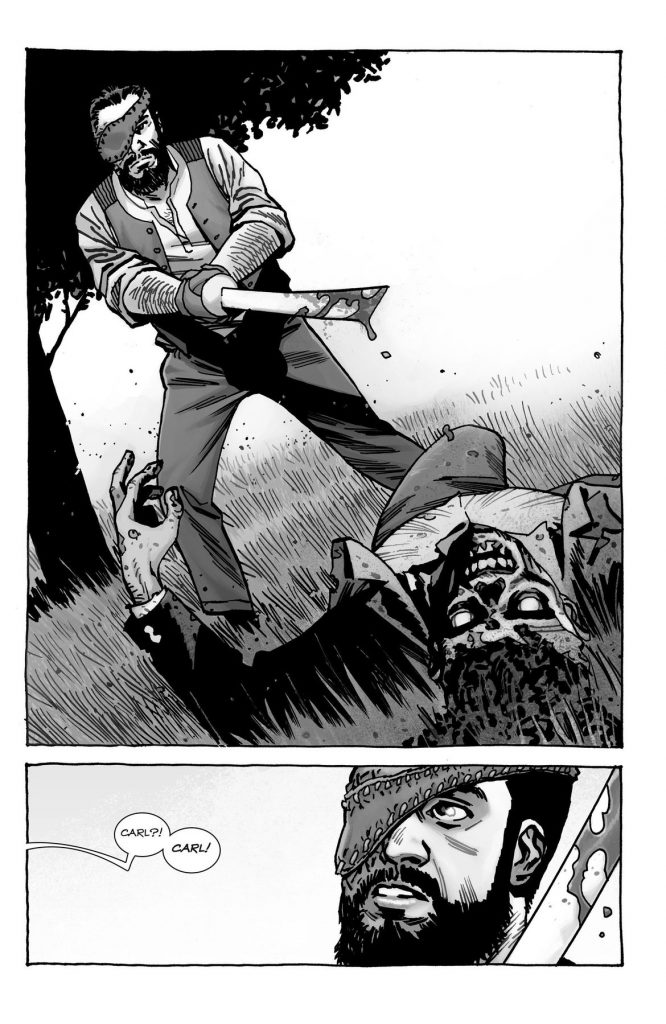

But it wasn’t the success of the series that the approach to this finale really fit. What it matched was how true to the core of the series it always was. It was always a series that hung its hat on surprise being used as a narrative weapon. No one was safe when you read The Walking Dead, as it firmly established at the end of its first arc when series lead Rick Grimes’ son Carl shot Rick’s best friend Shane – who, at that point, was arguably the second lead of the book – after Shane lost his mind out of jealousy.

I remember reading that in college and first thinking, “What in god’s name just happened?” and then quickly following that up with, “I need to read more of this.” That was a big deal for me. The Walking Dead was one of the three titles that brought me back into the medium of comics after a three-year hiatus from reading them. 2 Finishing that first trade and knowing I had to read the next arc was essential to me not just returning as a fan but continuing onwards from there. And it was built from the unique spice that Kirkman always brought to the book, that feeling of “anything can happen” that I noted above.

That’s why in many ways the story that best matched The Walking Dead’s path isn’t even a comic, but the aforementioned Game of Thrones. Both were stories heavily built on surprise, with the end of their first arc featuring game changing moments that made them feel a little different from their peers. 3 But where things really got interesting was what happened after the unexpected became expected.

Like with Thrones, The Walking Dead’s greatest enemy almost became expectations. After Shane’s death, The Governor, seemingly half of the cast being killed and replaced god knows how many times, Negan’s first appearance also bringing the demise of series favorite Glenn, etc. etc., we had become conditioned to believe that death was right around the corner. It created a bizarre bloodlust amongst readers, and as a long time fan of The Walking Dead’s seminal letters column, Letter Hacks, I found readers started to almost desire something bigger at every turn even if the comic was already working.

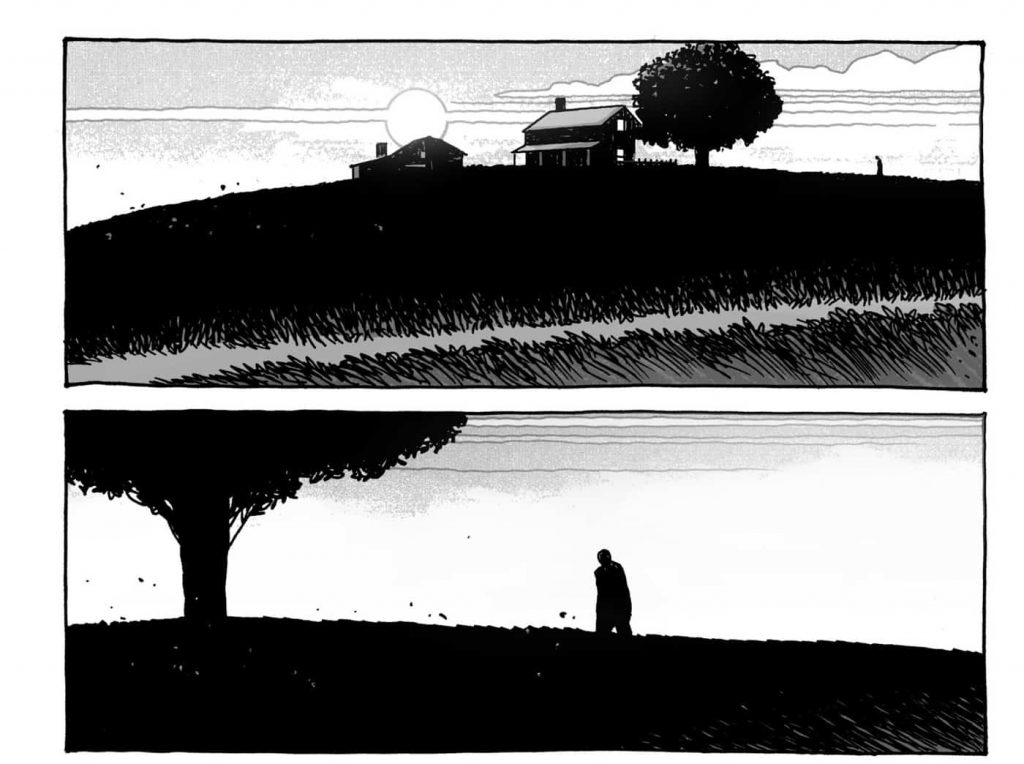

The funny thing about that was my favorite twist of the series came in issue #127, and it was by far the most unexpected thing the comic could do, save for its final turn this past Wednesday. After the turbo event arc All Out War, in which I’m pretty sure Kirkman was trying to kill Adlard through the title’s rather aggressive release schedule, we were given a taste of The Walking Dead’s world after it had found something completely unexpected: a time of peace. The comic leapt forward in time and we found that Alexandria – the town in which the majority of the main cast lived – was living in (relative) harmony with nearby communities, and there were previously foreign concepts like markets and commerce and – gasp! – happiness starting to take root.

It was just what the book needed, and looking back on it, it was the twist that created the path to this finale. We needed a reminder of what they were all fighting for to bring value to the ultimate sacrifices series lead Rick Grimes would have to make over the remaining 66 issues, and while it took a winding path in getting there, it did everything it needed to.

The irony about all of this, though, is over that span The Walking Dead also became something singularly unexpected for me as a reader. This series that was built on shock and death and surprise became one that almost replaced the emotions I had once gotten from Marvel and DC titles. Back when those publisher’s titles would run for hundreds of issues, I would get deeply invested in the cast and characters as long-term narratives would form and they’d follow paths rooted in moments long before. After those publishers became obsessed with relaunches, The Walking Dead became one of the few titles to live well into its hundreds. Ultimately, The Walking Dead scratched an itch I once got at the Big Two, as I found the same investment I once had in Wolverine and Bart Allen in the lives of Rick Grimes and Andrea and any number of other cast members.

It was a funny position to be in given Kirkman’s perceived contentious relationship with the way things were done at those houses, but it’s important to remember that Kirkman grew up reading those comics like many of us did, and his issue with them wasn’t in how they created passion amongst readers but in how they treated their creators. Bizarrely, The Walking Dead lived long enough to replace those titles for me as a reader, which was a surprising place for me to find myself as a long-time fan of the title.

But that period of status quo 4 acted as a the perfect set up for how the series concluded. Like I said, its ending fit the series to a “T,” as there was no greater narrative twist one of the largest comic empires could employ than randomly wrapping its run with its 193rd issue. 5 While I felt like something was up, as long-time inker Stefano Gaudiano surprisingly stepped away with issue #192 and series lead Rick Grimes was killed in the same comic, I certainly didn’t expect this.

And you know what? It was really the only way for a series fundamentally built on surprise to end, even if it goes against everything we’ve come to know and expect from the comic book medium. But that’s another reason I love it. It’s just so different. And if you’re Robert Kirkman, a man who likely has few needs anymore after the success of the larger media empire the show has become, why not find a new way to end a comic after deploying a new way to begin one with last year’s Die!Die!Die!? Most would have played it straight, ending it in a sea of press releases and textbook interviews, but Kirkman zigged when others would zagged. The issue was all the better for it.

Lastly, though, I loved the finale simply because I thought it was a tremendous comic. Sure, it had me hook, line and sinker because I’m a mark for square bound comics, but the actual story within was a lovely coda to everything that happened in the 192 issues that preceded it.

I often wondered how they might choose to end the series, as it was certainly one that didn’t have an obvious or even fitting point of conclusion. It made sense that Rick would die, but that’s not really an ending is it? That’s a death. We’ve done that before with The Walking Dead. Many times over, even. It didn’t make sense. What could it be then?

It ultimately was a flash forward to life well down the line after Rick’s death, with his son Carl now grown up – a husband and a father himself, just as Rick was at the beginning of the series – and acting as the lead, taking us through one last story that showed us what happened to the world and its denizens after his father’s demise. Consider it The Walking Dead’s version of the Parks and Recreation finale, as we get send offs for almost every key cast member as we tour a now functional if not antiquated version of society. Shocking note: my clubhouse leader for best send-off goes to Pamela and Sebastian Milton, the final story’s pair of villains, if you will, which was a shockingly poignant little moment.

And you know what? That was the only way it could end. When you look at the series as a whole, what was it but a look at how life goes on no matter what happens to us? How you can choose to let trauma define you, or you can choose to define yourself in the face of adversity. I remember in a recent edition of Letter Hacks, either Kirkman or series editor Sean Mackiewicz addressing the lack of usage of zombies in recent months, and it really underlined something that was always there even if readers didn’t want to admit it. The comic was never about zombies; it was about how life carries on in the face of death.

The series in many ways exists as a reversal of the standard narrative structure we see in stories like Blow or Goodfellas, where everything seems grand until it all breaks, and then you find out that leading a life of destruction has consequences. In The Walking Dead, we were given a story where the peak in the middle was actually one of misery, and it was ultimately about a group of people finding a way to rebuild not just society but their own internal reservoirs of hope despite the pain they’ve all gone through. This coda underlined that, acting as an insight into how important it is to remember the past even as you’re building a better future. It was a potent, emotional read that was perfectly built off the days gone by.

I have to give Charlie Adlard a lot of credit here. After 14 years on a book, it’d have been understandable to just want to be free of this eternal series. It had to be an exhausting and stressful run, and I imagine there was a certain level of relief when he found out this would be its final issue. But the title’s long-running artist pushed all that down, dug deep, and delivered what was his best work on the series in this final issue.

While some of it falls within that attribution trap that comics present – for example: it was just an absolutely exquisitely paced issue, with its extended page count letting the team luxuriate in moments when they previously might have had to rush through them, but it’s hard for me to say whether that was a script choice or an art choice 6 – Adlard’s character work gave every beat of this issue the weight it needed to hit and hit hard. Take the unexpected hit of Pamela and Sebastian Milton’s send-off as an example. That wouldn’t have hit at all unless it was executed well from a visual standpoint. Adlard threaded the needle and nailed those characters, giving it everything it needed to sing.

That’s how the whole issue worked, though, and while it wasn’t without its flaws – it leaned perhaps too heavily on Rick’s legacy throughout, and it would have been nice to give some of the cast a bit more agency as they all played a part in keeping this whole thing together 7 – its plusses vastly outweighed its minuses. It did what it needed to do, with its narrative perfectly matching the story’s themes, telling readers that it was never really about reaching an ending, but finding a way for life to continue on.

Ending a story is hard. I’ve written about that idea many times before, and it’s because it’s universally true regardless of medium. It doesn’t get any easier with success, I imagine, as finding a large audience both comes with expectations and what I have to believe is a nagging need to keep it going just because. There’s a fine line you have to walk to get a finale right, as you don’t want to end a story too soon because it may make the whole thing feel rushed or unearned – hello, Thrones! – and you don’t want to end it too late because that could destroy the connection you have with fans. 8 The Walking Dead’s team both found the right time to end their series and the right story to do it with, while using the success they had found on the title to do it in a way that allowed the issue to stand on its own merits.

It was a shocking conclusion, and one that really couldn’t have been done by any other series. I guess in that way, it makes it the perfect – and only – way this series could have ended, even if it was something we never expected.

Whether or not that happened depends on who you ask, as the success of titles like The Walking Dead, Chew and Saga certainly inspired many creators to migrate in that direction, even if it didn’t ultimately result in multimedia empires for all of them.↩

The other two were Y the Last Man and Fables.↩

The aforementioned death of Shane for TWD and Ned Stark’s beheading for Thrones.↩

Of sorts, as even a status quo isn’t very status-y or quo-y for The Walking Dead.↩

Some people seem genuinely annoyed about the series not concluding with issue #200, but I have to say: I love it. It’s such a flex by Kirkman, and it also made the whole thing feel that much more unexpected.↩

I’m calling it a tie, giving it to the larger concept of the faux cartoonist.↩

Plus, the storybook Carl reads to his daughter Andrea in the end would be an extremely unpopular children’s book, unless it was the only book available in the world.↩

While it may not be the best example, I always think of How I Met Your Mother as the best example here.↩