The Collecting Conundrum

The best way to succeed in the direct market isn’t by finding new readers; it’s by selling more to existing ones. That feels like a problem.

If you talk to anyone who works primarily in the direct market, 1 whether that’s retailers, publishers, or creators, one of the eternal questions they face is this: “How do we get more people reading comics?”

That’s understandable. The best path to a healthier, more vibrant comic industry is by attracting new readers, which we know and understand by looking a little bit off to the side at the book market 2 and its meteoric rise over the past 15 years or so. However, the direct market has a difficulty baked into it the book market lacks, and that’s because there’s a fundamental tension built into its core. Yes, single-issue comics are designed to be read and enjoyed. But they’re collectibles as well.

That isn’t inherently a problem.

I’m currently sitting in a room with 37 longboxes, one shortbox, and a spinner rack filled to the brim with comic books. Collecting comics can be fun, and it’s a bonus to the reading side for many. Having treasures like The Avengers #1 or personal favorites like Daredevil #8 3 in my comics life makes me enjoy them more. These wonders engender warm feelings amongst readers, and collectively, they tell a story about your relationship with the medium. That’s marvelous, a potent connection that fuels your passion for comics.

Where it becomes a struggle is when a balance is lost between those two sides of the comic world, as we’ve spent decades seeing the direct market fine-tune itself towards the collector side when it comes to single issues rather than the reader one. This creates an environment where efforts are seemingly designed to squeeze every cent out of existing customers rather than trying to build a more expansive readership.

And that’s a problem.

Sure, getting additional revenue out of your existing customer base is nothing new for a capitalist economy. That’s a basic tenet of every industry, even those in entertainment. In a normal year, movie studios would want you to see their films in theaters, rent them digitally, stream them on their streaming service, and then buy them when you realize it doesn’t make sense to keep renting. The difficulty for comics in the direct market versus other entertainment mediums, though, is outside of digital comics, there’s a finite amount of available product. So, by leaning into practices that encourage collecting – or even worse, collecting’s evil cousin, speculation – you’re fundamentally making it more difficult for new readers or even current readers to try something different out.

When your practices make it more onerous or expensive for those interested in reading comics to get onboard, that’s where the lever gets unbalanced. That isn’t a sustainable approach, at least without something to offset it in place. This tension between collecting and reading has been on my mind a lot lately, and so today, we’ll be exploring what’s throwing that balance off, as well as what options there are to resolve this issue, if anyone actually wants to do that.

We’ll begin in the place you’d likely expect: variant covers. Like collecting, variants are not inherently bad. They can be a great way to drive attention to titles thanks to the featured artist or because the quality of the work, 4 they can deliver exciting options for readers who want a different flavor from what they’re buying, and the incentive variety 5 can even be a way to encourage retailers to order more of a title that otherwise would see little opportunity to connect with readers.

In those ways, variants are a useful tool, a way to drive consumer attention and even commit them to a purchase. Plus, they’re not a comics exclusive phenomenon: even books and physical movies use them to a degree. To those reading, raise your hand if you’ve bought a new copy of a favorite book because it had a gorgeous new cover or the Criterion Collection of a movie you already own for the same reason. 6 Sure, they’re more abundant in comics, but they’re hardly foreign elsewhere.

The problem with variants arises when they become too much of the equation. Once upon a time, I was hopeful we wouldn’t get to that point. I wrote a feature in 2016 on variants, and as part of that, I spoke to a bevy of publishers about their thoughts on them. Based off those conversations, I said the following:

“While I think there’s a place for (variants), their ubiquitous nature is a detriment to their own value. The industry could stand to dial back the usage and rethink how they roll these products out to their customers. The good news is, from the sound of it, that’s happening. Marvel sharing they’re both considering how they employ them and working on a new method to simplify the ordering of percentage based incentive variants is big. Others, like Image, have already made adjustments to how they handle these items, while Oni and Dark Horse are approaching the subject with all players considered. Sure, the same can’t be said for every publisher, but we’re seeing positive movement at the top.”

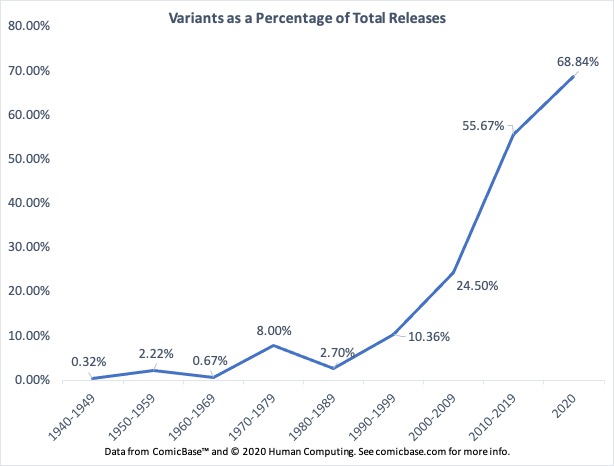

That positive movement is gone, as the only directions variants have headed since is up, up, up! Consider the following chart, which looks at variants as a percentage of total releases – meaning, of all releases in the market, the percentage that are variant covers – with that data coming from Peter Bickford of ComicBase. 7

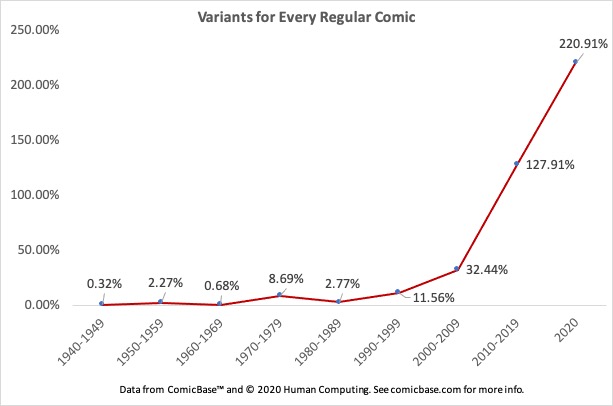

In ye olden days of comics, variants were barely a thing. They were predominantly price-based or related to the market they were being sold (or given away) in. Now? They’re dominant, with nearly 70% of releases in the direct market being a variant of some sort, up tremendously from the Aughts. When you look at it from a slightly different angle – the amount of variants for every comic release – the numbers are even more staggering.

This is expressed as a percentage, but here’s a quick tip: every 100% equals a variant relative to a regular cover. So that means in 2020, there have been about 2.21 variants released for every comic. While it’s easy to see in this chart that this trend is accelerating, as going from .32 variant covers per release to 2.21 in two decades is…quite the leap, it’s even more striking when you look at the numbers over just the past decade on a mostly year-by-year basis.

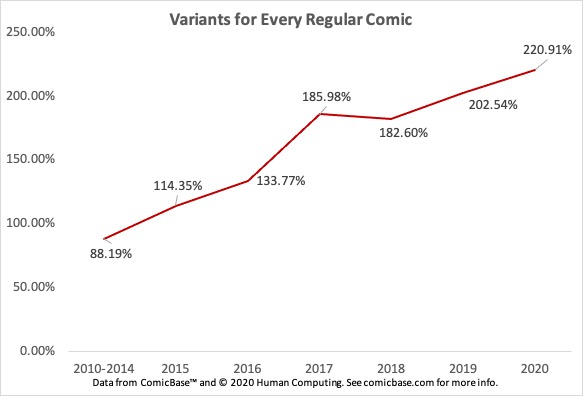

As you can see, there was a massive surge in the usage of variant covers the year after I wrote that aforementioned feature. While there was a slight drop off in 2018, it has went up considerably every other year, reaching its apex in 2020. Instead of adjusting to the overuse of variants as I was hoping they might in the conclusion of that piece, publishers have embraced them. 8

When I talked to a retailer about this data, they were careful to note that certain publishers like Dynamite and Boundless likely skew these numbers. And that’s true to a degree. Both of those houses often have dozens of variants per release. But in just the past decade, there were 68,236 variants released. 9 Dynamite and Boundless might carry more weight per release than other offenders, but this is clearly an everyone problem.

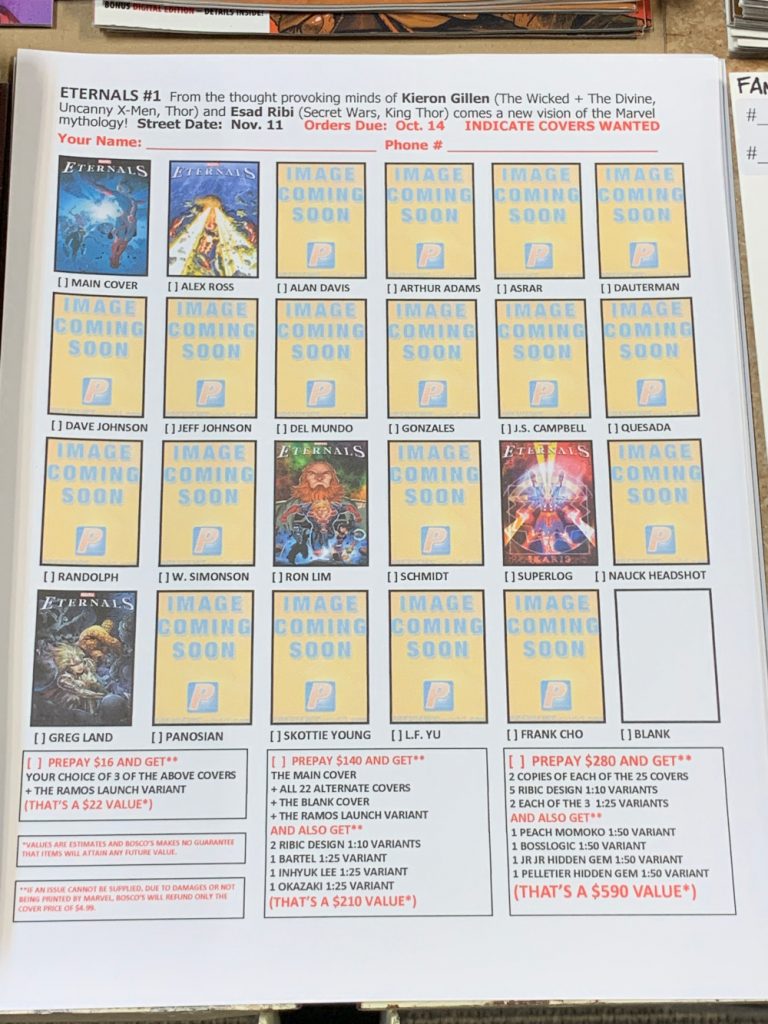

Consider Eternals #1 and its 40 or so covers, and how my local comic book shop had to put a one-sheeter out on the stands to help gauge interest in the litany of variants, with one level delivering an experience where the customer walks away with 65 copies of the same comic. Or BOOM! and its approach to its BRZRKR Kickstarter, where backers at one level would receive four different and increasingly limited editions of each volume of the series. 10 Or even Image – the staunchest opponent of variants for the longest time – and its embrace of incentive variants, as these tactics have fueled Department of Truth and Crossover’s massive order numbers.

Variants haven’t slowed since my 2016 feature; they’ve exploded while expanding their breadth of use, making stars out of cover artists like Artgerm and Peach Momoko as well as driving increased order numbers – but maybe not readers – in the process.

The question, of course, is “how is this a problem?” We’re talking about something that makes publishers more money and something many retailers profit from. That’s a win, right? These are inarguably smart short-term moves, at least from the publisher side. But are they as valuable in the mid to long-term? Color me skeptical.

The difficulty with variants lies in who they’re targeting. People who are comic book curious aren’t going to be motivated by a Peach Momoko incentive variant that’s limited to 500. Those are designed to get existing readers to buy more of the same thing, like the aforementioned Eternals #1 stratagem that results in a single person buying 65 copies of the same comic. This isn’t expanding the audience: it’s bleeding them dry without delivering a path for new readers.

If anything, variants can make it more difficult for new readers to get onboard. Many variants cost well above the already unattractive cover price, as comic shops try to make up value from their incentive-based nature, while order numbers for the main covers are often low enough that “hot” titles are eaten up by speculators before anyone who just wants to read the comic can get there. That isn’t a path to expansion; that’s a bubble, just waiting to be burst.

The other problem the direct market is facing here is when collecting transitions into speculation. While some would perhaps accurately define what happens in comics as arbitrage, as much of it is built on buying a “hot” comic today and selling it tomorrow to a keen audience, speculation is a blanket term everyone in comics understands. But in case you don’t, it is, in its simplest form, where someone buys up inventory of a comic containing a first appearance, rare cover, or some other element of supposed importance with intent to resell it at higher prices later.

After a long time away post the 1990s bubble bursting, speculation has returned in dramatic fashion over the past decade or so, largely coinciding with the rise of comic book movies and the heat connected to characters appearing in them. Pair that with a bevy of apps and YouTube shows dedicated to identifying “keys” 11 acting as an easy button to getting into the game, and all of a sudden shops are under siege whenever comics arrive as thirsty speculators descend upon them to eat up that week’s lottery ticket. Shops have attempted to adjust by paying attention to these shot-calling channels or by putting caps on how many copies of specific comics people can purchase, but this only makes their jobs more difficult.

It also makes it harder for readers to jump onboard with the new hot thing when enthusiasm spills into the broader comics sphere. Take X-Force #13, for example. This supremely okay comic was the fourth chapter of “X of Swords,” the first event of the new era of the X-Men. And because it marks the first cover appearance of Wolverine’s supposed new arch-nemesis Solem, it was enough to gain heat amongst speculators, with both the regular cover and Iban Coello’s incentive variant almost immediately selling at multiple times over cover price on eBay. 12

That in of itself is not a problem. But what it causes is. Let’s say you’re just an ordinary reader, not someone who updates their pull with regularity but someone who is interested in this “X of Swords” that people are talking about. You read X of Swords: Creation and X-Factor #4 and you’re like, “I’m in. This rules.” 13 The following Wednesday, you go in to buy your comics and what do you find if not plenty of copies of the other two tie-ins from the week but no X-Force #13. The shop offers to order you a second print that might arrive in a few weeks, but nah, that’s it. You’re out after two parts of this 22-chapter event.

That’s the cost to speculation. When the pursuit of a purely theoretically profit is enough to make it harder for new or even existing readers to get onboard with a comic, your ceiling is fundamentally limited. Because that speculator who jumped onboard for easy money off Solem’s first cover appearance? They likely won’t be back the following week for part six of “X of Swords,” as they’ll scurry over to the next hot item, which they can easily figure out the identity of by looking at push notifications from or the “Keys This Week” section of Key Collector Comics, a “key issue database and price guide” app.

Here’s where I eat crow. While I previously supported what Key Collector was doing, 14 I’ve officially moved over to the camp of this app being a net negative for the direct market. And something very specific led me to my reversal.

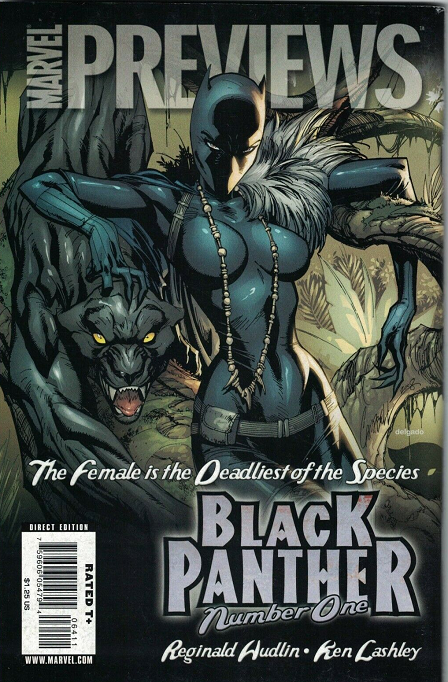

You see, every once in a while I peruse what’s hot on it, just to get a feel for what that world is doing. I took a look at the “Hot 10,” or a section highlighting ten issues from comic history that were notably “hot” in the secondary market that week. It was the week after Chadwick Boseman passed away, and the hottest “comic” from the lot was a copy of Marvel’s Previews magazine that featured the first appearance of Shuri as the Black Panther on its cover.

If a note from Key Collector Comics is enough to make a copy of Previews Magazine a desired object, then anything is on the table. And it’s made darlings of all kinds of comics not because they’re good or genuinely have any “importance.” Instead, it’s often because they’ve either been identified as such, allowing for a path for publishers to potentially court this market if they desire, 15 while at other times it can just be because they’re considered “rare” based off retailer orders.

That’s an important point to make, especially in this pandemic-affected year. When orders are low for titles – which they often are, even at Marvel and DC, simply because we’re in a tough market and due to there being so many comics to order each week – that inherently makes early prints 16 objects of desire for speculators simply because they’re limited. You can see it in Key Collector, which often labels retailer orders in the identifiers for titles.

And when comics cross a line from entertainment to pure commodities for the most agile buyers in the market, accessibility becomes an issue. If inventory goes straight to the secondary market, that can kill books and interest from your everyday comic readers. And that’s a problem for everyone in the direct market, both in the short and long terms.

That’s especially the case when publishers lean into these practices because they know it’s a way to generate heat, even if they also know it’s fundamentally built off unsustainable business practices. While it’s true that these methods generate the revenue these businesses desire, the difficulty lies in how many of the direct market’s publishers have seemingly shifted their focus in comic shops to extracting whatever they can out of the audience that remains.

There’s no greater offender in that regard than Marvel. Armed with a character list that has made its parent company billions and billions of dollars, what does Marvel largely do with it? Churn and burn, squeezing every ounce they can out of each and every title with variants and high velocity release schedules until there’s nothing left, at which point they start it all over with a new #1. It’s a tried and true method, as Marvel has effectively played this song on repeat since 2012, delivering seven line-wide relaunches over that span. 17

The person who largely receives the blame – or kudos, depending on your perspective – for these tactics is Marvel’s SVP of Sales and Marketing, David Gabriel. The Marvel exec previously told me 18 that he “personally heralded the return of variant covers” in 2005 with New Avengers #1. Now, he didn’t say that ruefully; he did so with pride. And I get it. The use of variants has earned Marvel considerable sums of money. But when he also told me that Marvel has “always affirmed that any retailer or customer who doesn’t want a variant, shouldn’t buy one,” it underlined how they view themselves as a supplier, and what the people do with the product is simply not their problem.

That’s a tough look, especially as Marvel’s usage of these tactics has only become more absurd in recent years. Consider the publisher’s hottest title right now, Venom. Typically, second, third, fourth prints of releases are designed to get the comic in the hands of readers as soon as possible, because it’s clear these titles are a success. New prints means new readers, or so the thinking goes. But when you look at a hot issue like Venom #25, they’re even using incentive variants like a 1:25 19 sketch cover by Ryan Stegman on third prints. Incredibly, later prints are speculator bait now, creating a confounding situation where I honestly can’t tell if Venom is actually popular with readers or just people who want to make a quick buck. If it’s the former, I can’t even imagine how successful it would be if Marvel approached it as a way to grow their audience rather than as a get rich quick scheme.

That’s a microcosm for everything we’re talking about here. When Marvel, the biggest publisher in the direct market, looks at popular titles as a path to maximizing earnings today no matter what rather than connecting with the audience of tomorrow, then we’re in an environment where they’ve admitted that they know who their customers are and that won’t change, at least with single issues.

That’s compounded by the fact that everyone seems to know that, especially as they study Marvel’s playbook. They recognize that the best 20 way to increase revenue is through arguably borderline predatory behavior, where they capitalize on the attractiveness of variants, lean into speculator interest, or even profit from the habitual, almost obsessive behavior of some comic fans. Think about what the old comic idea of a completionist means in 2020. You used to just get every issue. Now you’re positioned as not just needing every issue, but every iteration of every issue, creating a terribly unhealthy relationship with comics. And publishers take advantage of that.

When I talked to a retailer about this subject, they shared a story about a customer who was buying enough copies of each “X of Swords” chapter to have a complete set of the story under each title in their longboxes. That means all 22 chapters for Marauders, for X-Men, for Hellions, for New Mutants, etc. etc. That’s 198 copies of those comics, and that’s if you assume the person isn’t doing the same for the event’s one-shots. In financial parlance, that person is a whale, 21 and they’re someone that is increasingly counted on by publishers to carry the bottom line of the direct market.

That’s a genuinely awful place for comics to be.

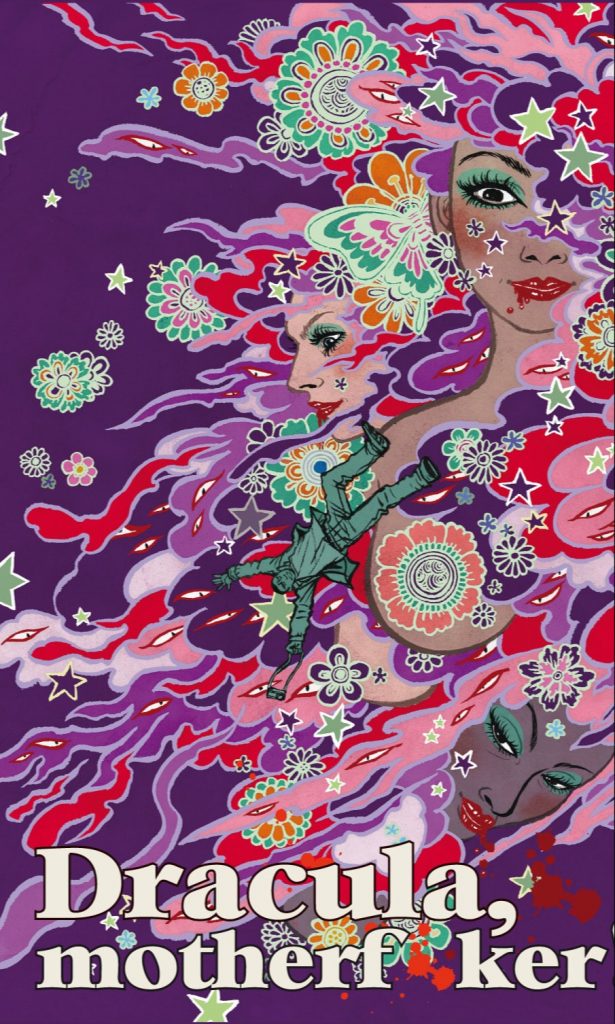

Now, as per usual, here’s where I backtrack a little. I’m not saying any of these tactics shouldn’t exist. Speculation is going to happen in any market where supply is finite and the air of demand can be created, whether you’re talking Tickle Me Elmo dolls, PS5s or the first appearance of Star. Variants can be useful and interesting – two I liked recently: the hardcover variant to the Nocterra #1 Collector’s Edition Scott Snyder and Tony Daniel crowd-funded 22 and the Bastard Title Edition of Dracula, Motherfucker! that came with a signed bookplate and a Yuko Shimizu dust jacket 23 – if deployed responsibly. Beyond that, if there’s a market there and people want to buy variants or speculate or whatever, publishers would be doing those customers and themselves a disservice by not serving them, to a degree.

But to elaborate on that animal-based financial term from before: whales are important…but finding new pods should be as well.

Super-serving one audience – collectors – to make up for your inability to connect with new readers creates an environment where the former can make it more difficult to deliver to the latter. That’s why everything I’m saying is not about abandoning one audience in pursuit of the other; it’s about finding a balance between the two, which has proven to be one of the great struggles in the current era of the direct market.

That’s of course easy to say and more difficult to do. It’s not like a change of heart will immediately result in new customers galore at comic shops worldwide. Instead, it’s more about changing approaches.

Here’s where we get weird. People often lament how one of the main roadblocks to connecting new readers with single-issue comics is that they aren’t in grocery stores or big box stores like Target or Wal-Mart. I get that. But I actually think that’s the wrong way to look at it, if only because single-issue comics as is are not an attractive product for a broader audience that wants to engage with comics as entertainment.

Meanwhile, at comic shops, all product adjustments are largely designed to get readers to buy more of a single product – i.e. variants – or to get them to spend more on higher end formats, like Black Label or what Marvel loves to do with its typically “anniversary” issues they charge $9.99 for. It’s extracting more and more money out of those that are already there.

In my mind, there are two distinct audiences of repeat customers that are mostly there to read and engage with the work: collectors and readers. Those should be, and likely are, the targets. And publishers already create products to super-serve existing collectors…but why aren’t they designing ones to speak to potential new readers as well? 24

Here’s a quick question as a follow up: why couldn’t Marvel produce the same single-issue content in two different formats, one on perhaps more inexpensive paper at a lower cover price – say, $2.99, at the very maximum – and one that’s on the regular paper at the usual price, with only the latter coming with variant options? Then consumers could choose whether they want the one strictly to read or the one to keep and protect…or both!

That lower price, same value option is likely part of the reason graphic novels for kids have thrived in the book market, as their atypical size has allowed for a lower price point of $12.99, 25 which seems incredibly attractive compared to something like Amazing Spider-Man #850, a $9.99 release that’s an incomplete story filled with extra materials that don’t necessarily do anything besides make the comic physically heftier.

There are almost certainly a multitude of reasons this would be difficult for Marvel to do, not the least of which are making the print runs a worthwhile size and the skepticism retailers might have about this lower cost, lower priced product. 26 Beyond that, they’d likely argue that trade paperbacks, graphic novels and their digital comics service Marvel Unlimited are their reader-centric products, especially after the latter example reduced its timeframe for new releases to arrive. But even saying that would be a tacit admission that they know the single-issue product is what I’m saying it is. And if they didn’t, it’s undeniable that the current path we’re on is the consumer equivalent of water dripping on a rock: you can’t see the rock degrading, but one day, it just won’t be there anymore.

I will say that some publishers do seem to have an eye on finding different ways to connect with readers. DC’s broader approach in the face of immense change may be designed to mitigate uncertainty, but structuring what they do around Black Label releases, their middle grade and young adult lines, lower cost digital titles, regular books, and even new options like Future State’s anthologies reveals a publisher that’s trying to find answers. Archie still has its physical products cooking, but they’re also attempting to connect with new readers on Webtoon and ComiXology Unlimited. Even a new publisher like Storyworlds is trying to find the right angle with their line of 50 to 60 page graphic novellas. Will they all work? Probably not. But I appreciate that they’re trying.

Typically, efforts like the ones we’re talking about haven’t been attractive in the direct market because they’re perceived as tactics that won’t work by both publishers and retailers. But not that long ago, mini-series were believed to be a place where comics go to die…until they weren’t. The world is changing, and the direct market needs to change with. At the top of my list would be finding a better balance between how they approach the collecting side of their consumer base and the reader one, because milking existing readers dry as your primary tactic is a one-way train to doom.

Again, I’m not saying you can’t embrace collectors and give them what they want. I legitimately just received notice of a variant being shipped to me 27 and last Friday, I wrote about how I would be buying an upcoming Carmen Carnero variant to X-Men #15 because I love it so. There is value here, both personally and to the industry. But if you’re going to do that, you need to find answers for the questions those actions create.

This is one situation where I believe you can have your cake and eat it too, even if it will take some risks from all parties to get there. I know risk is something everyone in the direct market fears, especially in a year as tenuous as this one. But for the direct market to not just survive but thrive in the future, they need to attract new readers. And to do that, it needs to start acting like they want them. That’s step one. What happens next is up to those in charge.

Or the side of the comics market that is encompassed by comic shops.↩

Or bookstores, big box stores like Target or Wal-Mart, libraries, etc.↩

The first appearance of my beloved Stilt-Man.↩

As noted in my recent comics marketing feature.↩

Meaning variants that shops have to order more of the main cover to earn access to.↩

*raises hand*↩

These numbers are for all releases from U.S. comic publishers.↩

Although I suppose you could argue that embracing them was the adjustment.↩

!!!!!!!!!!!↩

That’s one big Keanu Reeves fan!↩

Or potentially important releases, which are most often first appearances, rare covers or status quo changes.↩

That something as silly as a “first cover appearance” can trigger that shows we’re treading on unsteady ground in the speculation world already.↩

Which is a very natural reaction to those two comics.↩

The database appeals to me and it helped me identify key comics I didn’t even know I owned. Plus, it’s kind of fun! I still enjoy it personally for a number of reasons.↩

There’s a real latter-era Wizard Magazine vibe to Key Collector right now because of how it can pre-determine heat. That may not be intended but it feels like it’s there.↩

Or even later ones, as those are typically shorter runs!↩

There’s a reason I’ve facetiously labeled Marvel as “the boy who cried relaunch” in the past.↩

In that aforementioned feature on variants.↩

Meaning if a shop orders 25 regular copies, they can order one of the variant.↩

Or at least the quickest.↩

Or, effectively, a VIP customer who carries an inordinate amount of weight because of the money they spend.↩

It was limited to 5,000, there was still an unlimited version available, and later on there will be the regular comic to buy as well, so no one loses out.↩

Limited to a small selection of comic shops, this wasn’t designed as an order incentive but a product restricted to specific shops that did not affect regular inventory. That’s a value-add rather than something that impacts anyone negatively.↩

Of course there are trade paperbacks and graphic novels to serve these readers, but I’m talking about the single-issue product here.↩

Scholastic and First Second largely use that number for their books.↩

One thing I’ve heard from several retailers in the past is they believe comic publishers are sometimes leaving money on the table by not having higher cover prices. Going the opposite direction would be problematic if that belief is widespread.↩

The aforementioned edition of Dracula, Motherfucker!↩