The Art of Solicitations

A marketing tool above all, solicitations are a curiosity, and one that can contain real artfulness — if you’re willing to think outside the box.

“Nothing will ever be the same!”

“The biggest (insert character name here) story of all time!”

“This story must be seen to be believed!”

Comic fans are likely familiar with this type of phrasing. It’s the siren song of the comic book solicitation, 1 the write-ups paired with comic releases as a quick explainer when they go up for order. While these fusions of hype and summary are common in any entertainment form, single-issue comics in the direct market are a rare breed because of their sequential, monthly-ish nature. You must come up with something new for every issue, with the hope that this paragraph or so of text sells the comic for you. They’re kind of a weird, industry-specific anomaly because of that. But they’re a core part of the business.

The objective of a solicit can lead to a lot of big talk. Sometimes, a title might even deliver on those promises. But they’re marketing tools using marketing language; they’re not meant to be literal as much as they’re built for you to believe in. They’re guides for retailers and readers, signposts that say, “You should order/buy me,” depending on the audience.

And you know what? They sometimes work! They can be the exact hook a title needs to get a retailer to up their orders or draw a reader in. I know comics fans who analyze solicits to the tiniest detail, basking in the hype and hyperbole, both as a potential comic buyer and as someone who loves the build-up to something big. Solicits are a crucial part of the direct market ecosystem, even if their value depends on the person. I’m a good example of that range of impact: I don’t pay a lot of attention to solicits, save for when I use them to introduce a title during an episode of Off Panel.

But they are fascinating to me, if only because there’s an artfulness to them, when done well. While many are boilerplate, ‘(x story) will (verb) the (insert the larger universe here) (length of time)’-like breakdowns, you can tell that some take it seriously enough (or, in some cases, unseriously enough) to have a real impact.

While the preferred form has a practiced cadence, answering the key questions about a new release — who made it, what is it and what else is it like, when does it come out, why you should buy it — there are a bevy of ways to approach them. Many of my favorite solicits are those that think outside the box, like Donny Cates’ effort for Crossover #13 in which he delivers the solicit for the finale of the series, before realizing his mistake at the last second (i.e. this isn’t the finale) before audibling to a quick, “Oh this one is good too” type message. Does it tell me what the comic is about? No. Does it make me think about Crossover more than I did before? Absolutely. And that’s what solicits are there for: to build interest, however they can.

But they’re complicated messages, and ones that are difficult to get right. The complexity of this part of the comic making job comes from the need to serve multiple audiences simultaneously, each of whom want dramatically different things out of the experience. That’s where things can get a little wibbly wobbly, as a couple pros told me recently.

“The primary purpose of solicits is to let a retailer know how many copies of a book to order. To do that optimally you’d really have to be completely transparent with all information – as in, say ‘In this issue, X character dies, Y beat happens,’” writer Kieron Gillen said. “But it’s also read by the audience, so it can’t work like that.”

“You’re trying to tease fans and potential readers and get them excited about the book, but you’re also trying to convey critical information to retailers. Those may seem very similar, but they are very often at odds,” writer Matthew Rosenberg added. “You need a potential reader to be curious about a book, to have questions, and you want to keep them mostly in the dark so that when they do read the book it is a satisfying experience and they come back for me. You want retailers to know exactly what is happening, how to hand sell the thing, and to be prepared for what the comic buying public’s reaction will be when the book drops.

“So, writing good solicit copy is balancing those two things, while also trying to be noticed.”

That’s tricky messaging. Lean too far towards retailers to ensure they know the importance of an issue for ordering purposes and you might spoil it for your readers. Favor the sanctity of the story and you could anger comic shops when they underorder the next big thing because they didn’t know it was coming. It can be a tough line to walk.

For that reason, there are an array of approaches to these little snippets of text you might read on your favorite comic site or in Previews Magazine. But another factor in the divergent look and feel of solicits is the person behind them. Who writes them depends on the publisher and project. One major publisher rep described solicits as a team project, with their authors being anyone from editors or creators to sales and marketing teams.

And that makes sense when you think about it. No one knows the story itself better than creators and editors. But at the same time, solicits are fundamentally sales tools. Depending on the objective, the appropriate writer of these descriptions might change. That malleability seems to be fairly consistent, with its lean depending on the house. Sometimes the arrow points more towards creators, like when the title is at Image, a pure creator-owned publisher. With for-hire jobs, it might be on the editorial/sales & marketing side.

That’s why if you’re someone like Gillen, your role with solicits can shift wildly. He’s written his own solicits for both for-hire projects (Young Avengers) and original creations (The Wicked + The Divine). He’s also seen others script them on those types of projects. Sometimes he just tweaks ones written by others. The point is: it all depends! On the project. On the creator. On the publisher. On all kinds of factors.

And yet, while the approach and core writer may vary, it all comes back to one goal: selling the book. Whatever you do in a solicit is in service to that, even if it doesn’t always look the same.

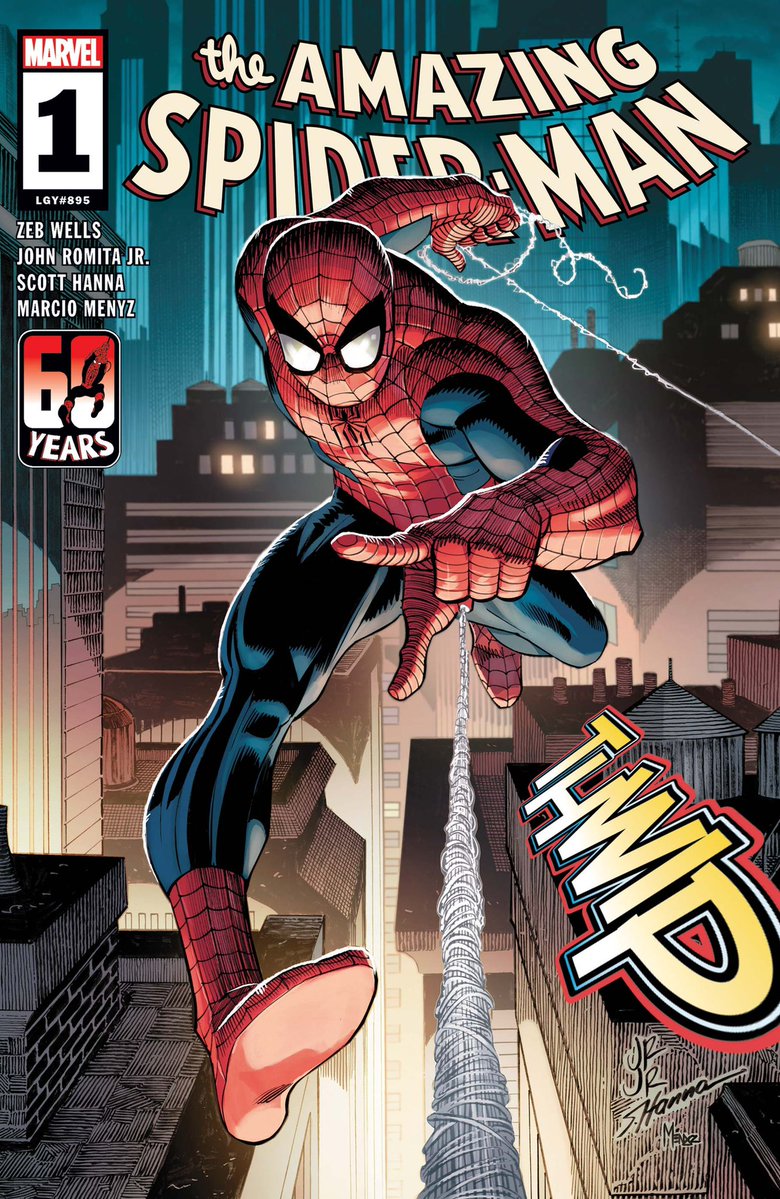

“I touch my WWSLD bracelet 2 and put myself in the shoes of a random person on the street,” shared Nick Lowe, Marvel’s Executive Editor of the Spider-Man line, when asked about his approach to solicitation writing. “How do I hook them? What information helps that? What gets the attention? What makes you want to read more? What is the least I can give away to grab someone by the metaphorical necktie and yank them into a comic book shop?”

For Adam Philips, the former Director of Marketing Services at DC and current Director of Marketing at Dynamite Entertainment, it all starts with positioning. Who the creative team is and why they’re the new hot thing. Where this story fits in the largest story. Why this issue is important, even relative to the other important ones. Philips keeps a retailer-centric view to his solicit writing, and he never wants “to hold back information retailers might use to make an informed buying decision,” even if you don’t want to “overload” them either.

“If the villain is Thanos or the guest-star is Nightwing, just say it — you can’t afford to be coy,” Philips told me. “Retailers have told me over and over that they don’t lose sales to spoilers, and that readers are much more invested in how something happens than anything else.”

The point is the sale, first and foremost. The key to effective solicit writing is delivering the important information to everyone involved — i.e. retailers and readers — in a way they can digest quickly and memorably. One retailer told me the core should always be what the title is about, what it’s similar to, who made it, and who it is for, all in a succinct fashion that limits hyperbole.

That isn’t necessarily easy. But it is important, especially early on for a title. As multiple people I talked to noted, the first issue tends to get the most value out of a solicit. Gillen told me that’s when “both retailer and consumer is most likely to be paying attention, because the solicit is one of the few data points anyone has.” Knowing quick, actionable phrases and targets for an early issue can help busy retailers handsell it with confidence. 3

Where things can get a little weird is later in a title’s run. For the most part, nothing sells a comic better than good sales data. That might sound paradoxical, but it’s true. The leading indicator of future orders for a comic book series are past sales. Once shops have data on that, it guides the way unless there’s a substantial change to the title that the solicit can note. 4 Because of that, both Gillen and Rosenberg noted that there’s a bit of time limit on the impact solicits can have, even if it isn’t always as clear cut as that might sound. At a certain point, your focus shifts, and solicit writing becomes less about the hard sell and about having fun or building a connection.

“After issue #3 in an arc, it probably doesn’t matter that much what you say,” Rosenberg told me. “There are no magic words to double your sales on a book mid-arc. So just say stuff to make people laugh or whatever. Why not?”

“I increasingly use solicits as a conversation with the most devoted bits of the audience, to shape and tease conversation months in advance of an issue’s release,” Gillen said about later run issues.

That’s where some of my favorite solicits come to life. Whether it’s something like what Cates did with Crossover #13, Rosenberg channeling David Byrne in What’s the Furthest Place from Here? #9’s teaser, or Gillen knowing just what his readers wanted from Young Avengers #3, the hook doesn’t always have to be a universe ending. Sometimes it can be about a vibe, something that builds a connection in a way that doesn’t traditionally make sense. I know some retailers might be shaking their heads at this idea. But anything that can be done to break up lethargy is important. This can do just that.

An issue’s place in a run or arc isn’t the only factor that affects one’s approach to solicit writing. The type of project the solicit is for can impact it as well. While Lowe said he’s “pretty consistent” with how he writes them — which makes sense, as he’s always tackling superhero projects in a single office — the others I spoke to try to deliver a different feel for each project and genre. For example, both Gillen and Rosenberg emphasized that they might dial back the jokes for a “more somber book” like Die or a horror title. The solicit should fit the issue it belongs to.

“You can easily change your language when you write about a horror series or a teen humor romp, and that’s another shortcut to tell retailers what they’re ordering,” Philips said. “Given how often creators cross genres, you need to start with solicit copy that tells retailers not just what’s going to happen but how it’s going to read.”

You want to match the tone of the solicit with the tone of the work, that way you can better guide retailers and readers to something for them. Writing your solicits so they fit your work and your audience can be important. For Gillen, it’s important that “every part of the book should speak to the book,” if only because everyone engages with the work differently. Some just read the comic to read the comic. 5 Others dive deep into everything related to their favorite. Solicits are part of that equation, in his eyes.

“I want to reward people,” Gillen said. “If you read the solicits, I want a joke in there, an insight, something that makes you glad you did it.”

The last thing I asked each of these solicit authors about was whether there was a way to build a better hook into solicits so even comic fans who largely ignore them — like myself — might start paying attention. While to a certain degree, that die has been cast, 6 there are some techniques those I talked to have found success with.

Philips suggested thinking of your solicit from a spatial standpoint. When a title is featured in Diamond’s Previews magazine, for example, it has an 8.5 by 11-inch page to operate within. Once you get the required bits down, it’s about optimizing the space. The veteran marketer said review quotes can help, and that headlines are an excellent “shortcut to tell retailers what’s important about an issue in just a few words,” even suggesting changing up fonts on the page to “add to a mood.” Anything that helps convey the quality and nature of a work quickly has value in a solicit.

Rosenberg believes it’s important to make “them feel a little more personal” because the “audience notices something that feels unique,” and it’s for a very industry-specific reason.

“Hundreds of comics are solicited every month and so much of it is just trying to convey information in a very efficient way. Make your text a conversation between you and your readers, you and the retailers buying your book,” Rosenberg said. “Make it feel like it comes from you and that goes a long way.” 7

When Gillen considered this subject, he hearkened back to his days as a games journalist. There was a presentation he had put together on marketing games, and in it, he acknowledged that many creatives hate marketing, which is why he believes it’s crucial to “make your marketing part of your creativity.” That’s something he sees in solicit writing as well. Writing solicits is hardly any creator’s idea of a good time. It’s a necessity as much as anything. But it’s one that can have value, if you can find a way to connect with it.

“How can you market as an extension of what you do? Do that. Make it yours, as that lands in a different way,” Gillen said. “Turning work you hate into work you love is a good thing to do. If you view marketing as eating your greens, it’s going to be hateful for you to do and the work will be bad.”

With all that said, solicits are still a bit of a mixed bag, even for some that I talked to, both on the record and off. Some retailers barely even pay attention to them, especially later in a run. Their impact on readers is equally nebulous. Even Gillen, someone who is one of the best in the business at the form, 8 would prefer they didn’t even exist, if only to let the comic tell its story when it’s released.

And yet, it’s clear they can make a difference even for someone like me, a solicit skeptic. I’ve bought comics because of them and was able to list efforts from the past, present, and future without even needing to search for them, simply because they stood out to me as a reader. If those who have mastered the art of solicitations can move the needle for me, maybe there’s value to the form. More than that, given the importance they have in the direct market — at least structurally — they’re here to stay. So, you might as well embrace it, and enjoy yourself while you’re at it.

“(Do solicits) make a difference? Yeah, probably not,” Gillen said. “But in the world we have, I figure why not have some fun with it, right?”

Or solicits as I’ll refer to them as going forward.↩

That’s ‘What would Stan Lee do?’ in case you were wondering. I was and Lowe glared at me through email because of my confusion. Nothing to see here, Nick!↩

A retailer cited the solicit for Kyle Starks and Artyom Topilin’s I Hate This Place #1 as a particularly good one, with comparison titles at the head, a quick explainer, and an explanation of where you might have seen the creative team making it easy to pitch. That’s nice!↩

Like a creative team change, first appearance, event tie-in, or if Stilt-Man happens to be in it.↩

*raises hand*↩

After all, it can be difficult to change the habits of people who have done things a certain way for a long time, as many in comics are far too aware of.↩

He added that he likes to hide a secret code in every solicit as well. “If you can crack the code, you can find me and we will go on a spicy adventure together. A word of caution: I determine the level of spice, not you.”↩

I polled a few trusted folks on the subject and he was largely the first person mentioned.↩