A History of Violence: Ulises Farinas on His New Creator-Owned Comic, Motro

The cartoonist talks his upcoming fantasy title at Oni Press

In this era of adaptations and serialization and sampling and spin-offs, people often opine about the lack of originality these days. Quality’s one thing, but even if something is enjoyable, is it fresh, some wonder? That’s all a matter of perspective, but if there’s one thing I know, it’s that cartoonist Ulises Farinas is not someone who has struggled to bring original ideas to life. In comics like Gamma and Amazing Forest, Farinas has proven himself as someone who can take a simple idea or inspiration and turn it into something unique and often bizarre (in a good way). Not only that, but his work rarely lacks in quality, with Gamma in particular being a personal favorite work over the past few years.

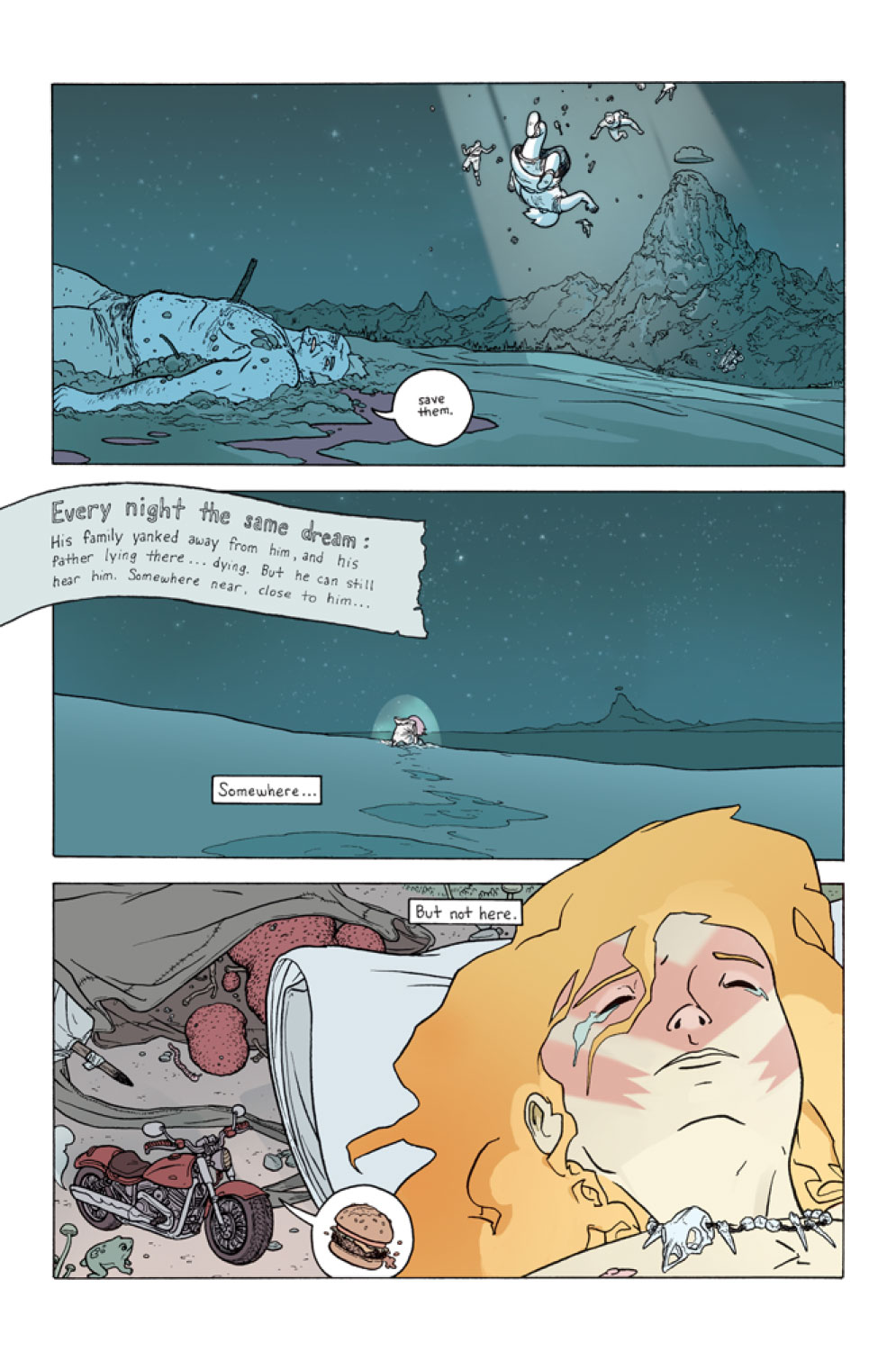

And coming this November at Oni Press, Farinas is back with a project long in the making: Motro. So what’s it all about? Officially, here’s the lowdown: “a reclusive young boy with superhuman strength follows a prophecy from his dead father on a mission to “save” people, but when he finds the area villagers are less than thrilled by his noble intentions, what will it take to fulfill his destiny? And can his miniature talking motorcycle help?” Unofficially, it’s about violence, growing up, finding out who you are, and a whole lot more (plus, the tiny motorcycle is pretty great). I’ve read the first issue, and it’s a tremendously unique and intriguing story that feels like Brandon Graham telling a fantasy story at the intersection of Kamandi and Mad Max. It’s pretty wild.

Today, we have a chat with Farinas about the book, where it’s headed, what its inspiration was, world building, what readers can expect from the book, and much more. There’s also a first look at the art of Motro, and as per usual with Farinas, it’s detailed and powerful stuff. Look for Motro in Previews this July and in comic shops this November.

I wanted to ask about your art background, but when doing some research for this, I came across an interview with you where you shared you went to the School of Visual Arts but dropped out because, more or less, you weren’t learning very much. What was it about that experience that convinced you school wasn’t necessary for you as an artist, and what has helped you the most in developing as a cartoonist?

UF: I can probably talk for hours about cartooning x formal education. But generally, a four year program for cartooning is like a four year program for grilled cheese. It’s not that difficult, and I’m much more interested in the one year programs I’m seeing popping up, like SAW in florida. That seems much more of a fit for learning the basics.

But trying to advance with your work post-education, it’s really about setting goals for yourself and making sure you have new challenges, even if it’s as simple as “draw faster” or “draw bigger,” sometimes that’s enough to get to the next level you’re trying to get to.

The first book I came across your work in was Gamma, which was a book I loved. Your work has shown up in a lot of different places though, from Gamma and Catalyst Comix to Amazing Forest and Judge Dredd: Mega-City Two. Hell, you even did a Where’s Waldo like Star Wars book. The point is you’re certainly not someone who is following any obvious path, but in an exciting way. What’s the appeal for you in that? Is it just reflective of your varied interests or is it more strategic in a way?

UF: I never really thought about having a set path. I just want to draw and make comics, and Motro in particular is a perfect example of everything I want to do in comics. I’ve been drawing it since before I began working full-time in comics/illustration, and I look at it as a project that constantly grows with me as an artist. When I’m 70, I want to be doing a version of Motro in some form. The only ‘path’ I try to follow is one where I’m constantly developing and refining my skills.

So Motro. That’s why we’re chatting, and I had seen before – as you said – that you have been working on this for a long time. It’s a project that’s clearly meaningful to you. What is it about Motro that compels you to keep coming back to it? And what makes it something that, as you said, you hope to be working on in some form for a long time?

UF: Motro is sort of this meditation on what it’s like to become a man. Not in the ‘get tough’ false machismo that most people think of first, but the way men have to learn to be more and more disconnected, unemotional, violent to be considered masculine. When I first began drawing it, it was very much a surreal coming-of-age story, where the character himself interacted with me, the Creator. The character’s ideas about what he wants to be when he grows up (a snowman) are childish and innocent, but what his father wants him to be, and what I (the Creator) put him through to get to become that, never allows for him to maintain any of his own desires.

As I write it now, the style itself has changed from when I first drew it, and it takes place after the major trauma of Motro’s life has past. The world is ‘real’ now, and to survive he can’t retreat into fantasy. Motro isn’t so much a straight narrative of a boy becoming warrior (each issue skips about ten years to another event in his life), but more about how far we can drift from what we imagined we would be. The way I wrote Motro at 20 is different than how I write Motro at 30, in the same way that Motro’s perspective on his own life at 12 and 120 changes.

While the first issue is, more or less, about a young boy’s attempts to save a nearby village from marauders, that’s not the long term story it seems. What’s Motro all about, and what are you looking to dig into in its pages?

UF: I think a lot about how we constantly read stories about men punching other men and monsters and creatures for a lifetime, but never really think of the emotional toll that has on a person. Violence isn’t easy, violence isn’t forgettable, and when we are violent, it’s easy to depict a man covered in scars as a shorthand for “TOUGH DUDE”, but that’s simplistic. I’d rather think of a Conan the Barbarian type character, not as an odyssey of perpetuating violence but as a victim of violence.

Each issue, Motro has to wrestle with the consequences of his violent actions. Its not a focus of the story, but Motro is superhumanly strong, and in the first issue and beginning of his life he is a pacifist. He has to be a pacifist when he can easily maim or kill a person. There is no in-story explanation why he is stronger than everyone, it’s simply to emphasize on a symbolic-level, how high the cost is to decide to hurt anyone.

As a cartoonist, you can work any way you please, I imagine. What’s your process for bringing Motro to life? It sounds like you’re very much an art first cartoonist, but I could be completely wrong!

UF: Motro is interesting because it has two art styles. When I first began drawing Motro, I drew in a very iconographic style, and now it’s moved away from that. They are the same story, and those first pages are still ‘canon’. But I’ve decided that the pages I drew when I was 20 are the in-story diary pages of Motro himself, which explains why he’s so much chubbier and why other characters tell stories using sequential art (I call those pages Proto Motro). These issues of Motro, occasionally you still see glimpses of that old art style, whether through Motro’s journals or later on when others are recording his story.

I don’t really have an art or writing first style. I write a rough outline/script, I draw the pages, and then I rewrite the script as I letter. It kind of all comes together at once, in the final hours. I usually don’t really know exactly how the story will read until I’m completely finished, and even then, I may rewrite it or redraw an entire page.

You talk about the impact of Motro’s violent actions, and that’s one thing that really stood out about the first issue: there’s a real sadness to it. Not that you have to achieve this, but as you’re developing the book, have you tried to balance that with any lighter elements? Or are you trying to just go where the book takes you?

UF: I write the book like I’m describing a memory, where there’s always a hint of nostalgia/sadness for how things used to be. I think even happy memories end up getting this vibe. Most of my other work with my co-writer Erick Freitas, like Gamma or Judge Dredd, are usually straight comedies or satires, but with Motro I wanted to confine it to a narrow range of emotions, to give that “just sitting outside while it’s snowing” feel.

While many aspects of the world are similar to the one we know, there are some real outside the box elements to it too that definitely feel like a Ulises Farinas creation. Namely, Motro’s tiny motorcycle BFF Wheeliebeast and the existence of sentient tanks, called Tankerbeasts. When you’re developing a comic like this, how much of the world building is you just having fun and filling a book with elements that fit what you like to do, and how much is finding the right fit for the story? Or is it generally a mix of both?

UF: The world building is one of my favorite parts in developing a story, but I always feel it’s important to keep it under the surface. I keep an online encyclopedia to keep track of the story and world building elements, and creatures like the Wheeliebeast are essentially Golems – mechanical beings endowed with life. But rather than have very typical fantasy tropes, like a giant walking pile of rocks or elves, I’d rather reinvent them. Dwarves are an asexual parasitic hivemind that are used as slave labor (you can see them in issue 2 cleaning/undressing Motro), Ghosts are emotional detritivores (what we think of as hauntings are simply these creatures gathering to feed off of intense emotional events. Predatory ghosts seek to cause these events, whereas grazers are harmless spectres).

Most of these elements only help to provide a distinct visual vocabulary for the world, while the story remains confined to the inner life of the main character. I don’t find that a talking motorcycle is so much different than say a talking sword, so why keep repeating tropes that served someone else’s story but don’t serve mine?

While we’re still a ways out – the first issue isn’t dropping until November – this is a project you’re clearly already pretty deep into. How many issues do you think you’ll have completed before that first issue even arrives?

UF: I’m planning to do it in two sections of six issues each. I hope to have all six issues done, though, so wish me luck!

There are tons of comics out there these days, but I can say this with 100% certainty – there aren’t any others like Motro. I know this is often one of the hardest questions to answer for a creator, but why do you think people should give Motro a shot?

UF: Beyond any other ideas that I’m messing with, that I spoke about in the earlier questions, I just am enjoying making this world, and I really hope and think that comes through. There is more to fantasy than elves and knights and monarchies, and I think it’s a genre that can be explored as deeply as science fiction. If you like talking tiny motorcycles, then you should give Motro a shot!

Look for Motro #1 by Ulises Farinas by Oni Press on November 2nd, and in July’s Previews magazine.