“We Can Collaboratively Try to Make Hits”: Vault Comics’ Damian Wassel on a New Approach to Number Ones

It’s a weird time in comics retail, and maybe even a weirder time for those making original comics. Where it gets even more challenging those two spaces is when the two are fused together, as it’s an increasingly tough sell for retailers to buy into original ideas in comics that don’t come with baked in brand recognition. To paraphrase a retailer I once talked to, when it’s tough to sell the big, famous superheroes, it’s even more challenging to pitch readers on something completely new. That’s led to shops dialing back orders and playing it safe. After all, can you really go deep on a new book if it’s just going to get left on your shelves?

That’s tough for shops and creators, but it’s also a challenge for publishers. How can you get shops to buy your “new hot comic” if you can only prove it’s two of those words?

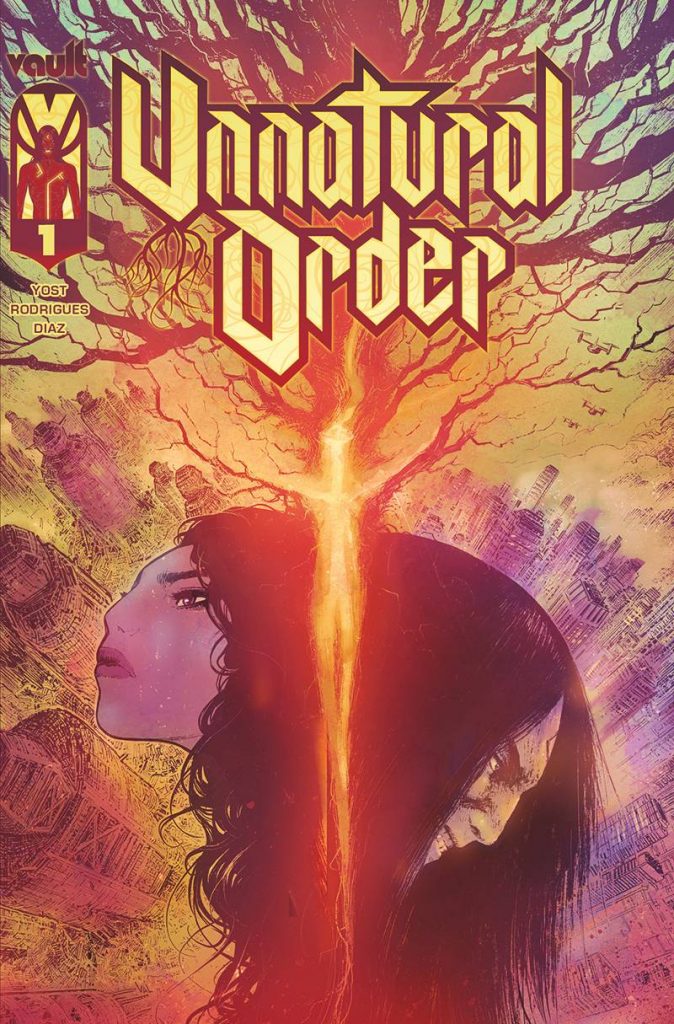

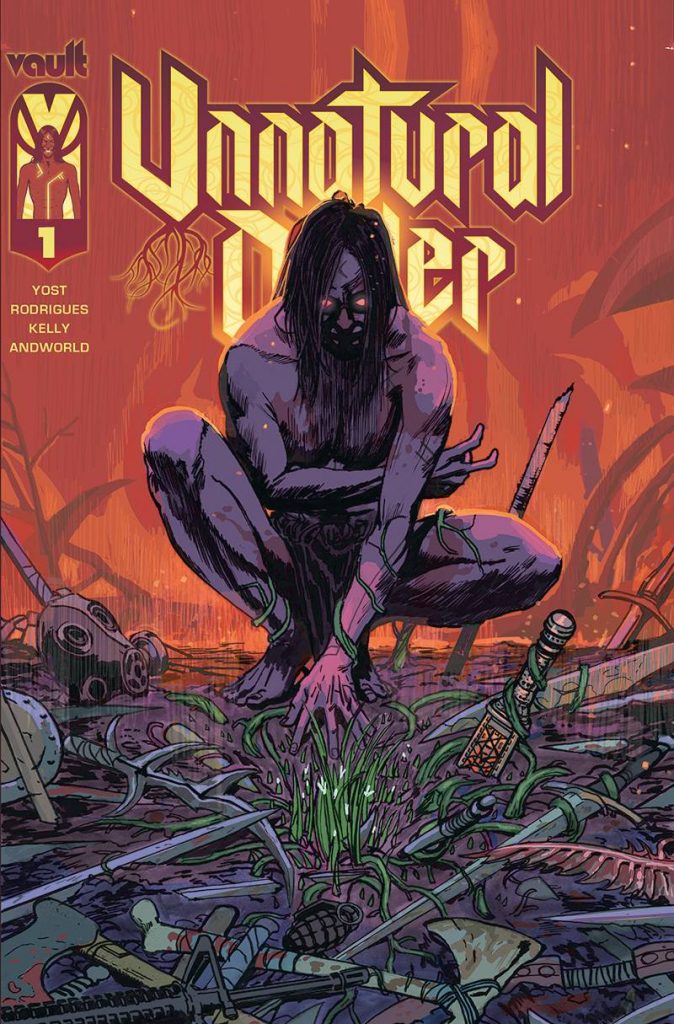

Vault Comics came up with a solution, and one that’s seemingly worked stunningly well: What if shops didn’t have to buy it at all? For Christopher Yost and Val Rodrigues’ new fantasy series at the publisher, Unnatural Order, they’ve taken the unconventional path of giving the first issue away to shops for free, with no caveats save for the fact it’s only Rodrigues’ A cover that’s free and that you have to order in bundles of 25. While the initial news came and went quickly, with some I talked to pshawing it with the greatest of ease, I thought it was ingenious. 1 More than that, I thought it would work.

Turns out I was right! The first issue brought in orders that reached a minimum of 137,000, which is several orders of magnitude above where Vault titles typically land. If the goal was to increase interest and to get their foot in the door, then Vault succeeded — and then some. Of course, it’s only one step along the journey, with its full story being told when Unnatural Order #1 actually arrives in shops and everyone gets to find out how customers respond, and then when subsequent issues arrive down the line. That’s when questions will really be answered.

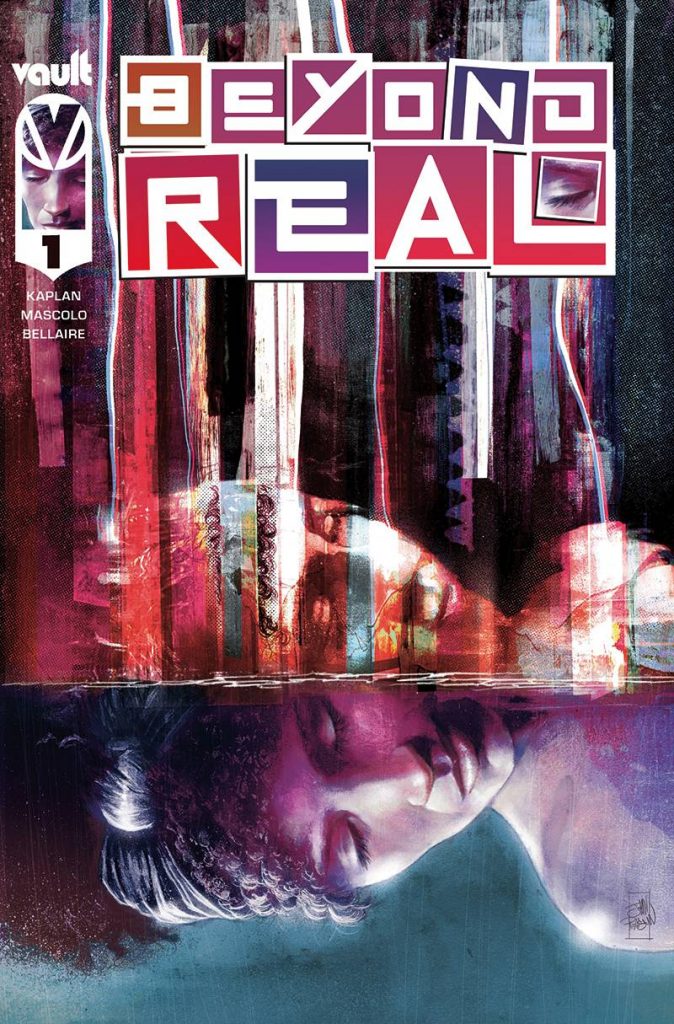

Vault has seen enough, though, announcing that the upcoming Beyond Real #1 from artist Zack Kaplan and a slew of artists that include Jorge Corona and Liana Kangas will be free to shops as well. This wasn’t a one-time thing. It was successful enough they want to do it again, and perhaps again down the line. It’s a fascinating choice, and one I was pretty interested to talk about given its alternate path to finding an audience. How does it pencil out? What problems does it solve? What’s the key to the plan? These were all questions in my head, and to some degree, questions I was able to ask when I recently sat down with Vault’s CEO & Publisher Damian Wassel to get in the weeds about this very topic.

That’s what you can read below, and let me tell you: this is about as inside baseball as you can get. But it’s a good chat about a fascinating approach, and one that seems to be working, and working well. It’s been edited for length and clarity, and it’s also open to non-subscribers. If you enjoy this conversation, please consider subscribing to SKTCHD, as the site and the work I put into it is entirely funded by subscribers.

Unnatural Order #1’s grand plan of being free for comic shops to order has seemingly went well. It generated a reported 137,000 plus in orders, although it seems that it was more like 150,000 plus total copies ordered when finalized. The way David (Dissanayake, Vault’s Vice President of Sales & Marketing) talks about it makes it seem like this plan has allowed you all to see into The Matrix of the direct market, which is why I guess you’re doing it again with Beyond Real #1. Obviously, the order number is great, but what is it about this plan that you think is working?

Damian Wassel: I think we can answer that question with two points. And I think they’re two points that respond to two problems the market faces, and in particular the indie end of the market faces. One of those problems is a problem of scale. It has historically, especially recently, been very hard to launch an indie comic at a scale that enables it to make shelf impact, market impact, or marketing impact. These are very real factors that affect the performance of a book and the perception of the title in the retail landscape. For obvious reasons.

Retailers have had to change how they order in recent years. There are macroeconomic pressures affecting all of us that generate microeconomic pressures which affect the retailers, and it has shifted audience behavior. One of the obvious ways to address those challenges is to put more units in the market. But you can’t just go to retailers and say buy more units. (laughs)

Well, you can.

Damian: You can. It doesn’t necessarily work.

Right.

Damian: But if you can think through it and run the spreadsheets and say, “Alright, if we can hit these numbers and then we see these attrition rates, then at the end of the day we’ll be better off. The retailers will be better off. Everyone will see better performance across the lifetime of this title.” So how do we just hit those numbers? We’d run this conversation time and again internally, and it was like, “How do we just do this?” And then we finally were like, “Well, what if we just say, have as many of the book as you want,” and then we’ll watch the effects be borne out on issues two, three, four, the trade, etc. of this title. That’s the first problem. The first problem was how do we address scale so that we can see sustainability in the title throughout its life.

How do we address that scale issue so that #2, even at prevailing reader retention rates or lower #2 is still hitting numbers that are meaningful. Obviously you’re familiar with typical attrition rates in the market and if we saw double the typical attrition rates that the market delivers, we’d still be doing very well as a result of this initiative. And that’s exciting for us. (laughs) It’s exciting to know that we can hit attrition like that and still see real impact. And look, that’s an answer that speaks to this problem as a problem we all face as independent vendors together, arm in arm. But we don’t do this business arm in arm, sometimes to our detriment, sometimes to our benefit. (laughs) And when we think about this in the adversarial frame rather than the cooperative frame, this gives us a tremendous amount of shelf impact, retailer presence, mindshare. It creates a marketing moment for every title.

It demonstrates to other businesses that we might be doing B2B deals with down the line, be that book market retailers or people interested in developing different rights categories, a scale of performance that is extremely hard to match with the conventional sales model. We think of this as an opportunity to both cooperatively and adversarially address that scale problem.

The other issue that retailers have had to navigate is increasing risk, and I think it’s really easy to lose sight of how seriously they’ve translated into real microeconomic pressures for retailers. The cost of capital is up because interest rates are up. Currently leased commercial real estate has gone up as landlords have tried to cover losses in other areas of their portfolio. This is a strange approach to take, but it’s also typical in the history of real estate leasing. When you see vacancy rates increase, you see rental rates go up on currently leased properties.

Retailers are navigating all these things, and it just means that the cash they have to order and take risks on new titles is reduced. And that’s the trickiest part of being an independent comics publisher. Generally speaking, we all have…call them renewable wells that we can go back to, IP that continues to perform every time you put a new iteration of it in the market. But we’re also constantly debuting new stories, and there is an enormous amount of uncertainty around those which stacks into this risk stack the retailers are already having to manage. And we’ve tried different approaches to mitigate risk and talked to retailers about those different approaches.

Take returnability, for example. I’m not going to name names, but accounts that we really trust, who sort of have a finger on the pulse, have said returnability doesn’t really lead them to order more of a title. It just leads them to feel more comfortable hovering at the ceiling we know we can expect with that publisher. And again, we started asking, “How do we create an ordering environment for them where they’re so de-risked, they’re willing to believe in a title and try to make a hit?” And that’s what we conjured up here. An approach where we can collaboratively try to make hits instead of collaboratively trying to subsist.

You’re trying to thrive, not survive.

Damian: Something like that. Yeah, if Beyoncé were to write a song about it, that’s probably how she’d characterize it. (laughs)

You hit two of my most common touchstones lately, which are risk and attrition. But before we get to those, how long have you been considering this play? Is this something that’s been around for a bit, or is this something that was born with Unnatural Order?

Damian: The honest answer is five years. (David laughs)

I have been thinking about this for ages. There’s been a bit of a “Why now?” question. There’s also been just a bit of a “How do I make this make sense to other people?” question. (laughs) It took me a lot of percolating to reach a point where I thought this was the right move. There are reasons that it makes more sense now than it would’ve made five years ago.

Many of those macroeconomic factors we’ve already talked about make it make more sense now than it did previously.

I also think that just simply put, five years ago you could have made it free, but Vault wouldn’t have had the awareness in the market and the trust in the market to make this meaningful. Retailers would just be like, “Why do I care about this free comic from somebody I don’t know?”

Damian: You said it, so I didn’t have to. (laughs)

I don’t know if this is a hot take. I didn’t see anybody else emphasize it which I find very strange. I think the secret sauce to the whole thing was that they had to be ordered in 25 copy bundles. If you just made it free and they could get three copies, it really wouldn’t lift your ceiling that much. They would still be risk averse because they still have to carry that inventory. The 25 copy bundles ensures that they must take a decent amount, and certainly for a lot of them, much more than they would normally get for a Vault book. Why was that essential to this plan?

Damian: I think you just answered your own question. Do you want me to elaborate? (laughs)

Please. I mean that was just a guess. I don’t work for you! (laughs)

Damian: Let me try to phrase this in a way that doesn’t make me sound like a big jerk. (David laughs)

What we want to do whenever we think about creating a sales tool that we’re going to communicate with a conventional sales value proposition is embed this in an ordering structure that facilitates what is, from our perspective, something that is best for us and the retail environment. Obviously we’re not going to run around telling retailers how to run their business. We try very hard not to do that. That’s why we’re distributor agnostic.

With that said, we like to think about how to set up the offering structures that we put out there that enable the retailers that want to take advantage of them to do business in a way that’s good for us and in a way we think is good for them. Frankly, having three free copies of a thing doesn’t do anyone any good. It doesn’t do us any good and it doesn’t enable them to get customers excited about it.

It doesn’t get you the scale you’re looking for, which is one of the two big pillars. But as I’m sure you’re very aware, retailer response to things like this can sometimes start with extreme aversion. They’re not into it, but then acceptance hits, and then, “Okay, maybe this is not a bad idea.” I’m curious as to what the retail response was for this because it doesn’t really have downside for them besides the fact that they would have to carry a little bit more inventory than they would normally.

Damian: Yeah. You framed out three tiers of retailer acceptance. This is some kind of stages of grief model, but for comics. (laughs)

Pretty much.

Damian: And I think we leapfrogged all three of those and went to stage four or stage four plus, which was extreme enthusiastic acceptance in nearly every case. I mean we did something like 500 retailer outreach calls to walk through this and how we thought that it could work for retailers and could work for us. Other folks on our sales team did the lion’s share of those calls. David (Dissanayake) and I talked to a few of our top accounts, just in terms of volume and also quality of communication. Those things vary from retailer to retailer, and overwhelmingly the answer was immediately, “We see what you’re trying to do for us in the market and we’re 100% behind it.” We had retailers tell us, “Okay, we think we’ll do X, we’ll get back to you.” And then when we actually got the data, they ordered twice as many units as they said they thought they would.

They’ve been very communicative with us about how, if we were to continue this, how we could make it function best for them, for us, and how to help make sure they can deliver the best numbers on #2. We’ve heard from retailers a hundred different ideas about how to incentivize customers to pick up that #1 ranging from some accounts saying we’re just going to put one in literally every customer who has a pull box. We’re going to give one to every customer who buys a new #1 on its release day, or we’re going to give one to any customer who subscribes to two and three.

Or they are going to sell them and are going to make $5 on every one that they sell, but then they are going to earmark those dollars for ordering more from Vault. We’ve had every one of those options put in front of us by a number of different folks, and then others zanier ideas that we wouldn’t have thought of that would take too long to walk through. We got, I think nearly 100% buy-in even some of the more skeptical and vocal players in the retail landscape. They came to us with a, “I don’t necessarily want to endorse this, but I don’t understand how it could be bad,” kind of approach.

This is very unusual. Most of the time when I hear about direct market stuff, it’s not exactly the most collaborative or cooperative world. It sounds like they were so bought in that they were willing to work with you to find answers on all the other problems down the line.

Can I bring up the biggest problems to this plan, at least in my mind?

Damian: Yeah, go for it.

I think you’ve solved half the problem: getting shops to carry Unnatural Order #1. The other half of the other half of the problem is getting readers to buy these or whatever shops end up doing to what they decide to do with their inventory, whether it’s giving it away or something else. It can still be a hard sell even if they’re given away. Are you doing anything to push customers into shops to get the comic, or is it just in the shop’s hands now?

Damian: We’re doing all sorts of things to do that. We do things to do that on a regular basis. We run geo-targeted ads driving people to comic shops in their locations. We cross-promote across our entire catalog to encourage people to pick up the next book. We coordinate with retailers who are interested in doing so to provide them with additional assets. We do conventional marketing pushes. We try to get folks in the key comics podcast environment talking about their work.

There are all those levers that we can pull. At the end of the day, there are a lot of things we can’t do. I think to pull from a different retail example, I would venture to say that Trader Joe’s is better at getting people to buy bananas when they’re on sale than Food Lion is because they do a better job with their own in-store and out of store marketing and that’s the part I can’t force on any retail account. Even if I tried, it’s not a one size fits all approach.

That’s one of the things that’s excellent about the comic book direct market, and it’s one of the things that’s a recurring challenge about the comic book direct market. What has to be done to get a Third Eye customer to buy a thing is probably different than what has to be done to get a Midtown customer to buy a thing. And it’s probably different than what has to be done to get a Coliseum customer to buy a thing. And of course, there’s some overlap. Creating awareness is important. But there are different people in different parts of the country with different buying habits and different times of day that they show up and different things they’re interested in and the stores are arranged differently and all of that.

We are stacking this on top of other tools to help retailers promote the book in store, including in store displays for Vault titles that they can put wherever is convenient for them. And we’ve had a number of retailers ask, “Would it be okay if we did this?” “Could you create this for us?” “Can you create a giant piece of art that I can print as a four by 12-foot window sticker poster that I’m going to stick in the front windows of my shop?” (David laughs) Apparently, there’s a retailer out there as a printer capable of doing this so he can change his own window decorations as he sees fit.

I was going to say, that’s such a specific example, it had to be real.

Damian: Yes. But it’s a combination of opportunity and problem of this retail landscape, which is that I can’t change how any individual retailer runs their business. Nor would I want to. And that means that I can’t hand them all the same bag of tools to solve the problem.

The other half of the other half of the problem is something you already brought up: attrition.

For readers that don’t know attrition, we’re talking about what happens with #2, #3, #4 and beyond. What happens with orders, but also what happens with customers buying it because free or not, shops will decide what they want to do with #2 based off the response to #1. It’s a lot easier to get it in their hands if it’s already free, but you already brought this up, the plan seemingly is to give you a much higher attrition floor. Effectively, if you have a big drop, you’re still probably going to be above where you are with normal #1s for Vault to some degree. How much of this was a play against attrition?

Damian: A lot of it was a play against attrition. I mean the unit economics of new comic series in the current printing landscape, they work fairly well on first issues and they get less charming on second issues and they can start to get troubling come issue four. And we’ve seen different publishers take different approaches to solving this problem. One approach that we’ve seen that I think is likely to be contentious, is the Marvel #1 price point move, right? That’s not to fix the gross margin on #1. #1 generally doesn’t have a problem with gross margin. That’s clearly a move to fix the gross margin on #4 or #3 or wherever they start to get squirrely about their gross margin. So, this is very much a play against attrition.

I think it’s not a super current problem. Our attrition numbers haven’t changed all that much in five years. It’s gotten a little worse recently. It hasn’t gotten dramatically worse. You can’t really fix that problem with conventional marketing, especially not conventional marketing in this day and age. We don’t operate in the kind of environment where a typical sales funnel can do its work. There are too many points of leakage in the marketer’s way of thinking about this. I can put a call to action in there, but I can’t track whether the call to action is working directly. I don’t have the ability to retarget interested customers. I can’t send abandoned cart emails.

None of that works in the direct market. None of those tools can connect with the audience. It’d be awesome if we had the opportunity to do that jointly. There’ve been some software companies that have cropped up and promised that but not delivered that. They’ve delivered other great things. They haven’t delivered those things and so we can’t fix the problem with marketing.

The question became, “Can we fix the problem with math?” (laughs) That’s my background prior to doing this. I was a math teacher and then I was a researcher in philosophy and mathematical economics, and sometimes I just ask, “Is there a scale effect we can benefit from? How do we achieve that scale effect?” Here’s a case where there’s definitely a scale effect. If we can multiply a certain number by 10, then we have a lot more tolerance in numbers that are dependent on that number.

I was going to bring up the price points part of it. Unnatural Order #1 being free would’ve stood out no matter what in the same way as when Image did those 25 cent copies of Saga and the Walking Dead a few years ago stood out. It’s a super low price point. You can’t get lower than free. But at the same time when big releases are arriving with $9.99 first issues or $8.99 first issues, it really stands out. I mean, going back to the promotional part, it’s to the point you got a lot of earned media from this. You don’t have to publicize yourself because it was a big enough deal already. Wasn’t it The Hollywood Reporter where it debuted? You receive coverage because of how different it is.

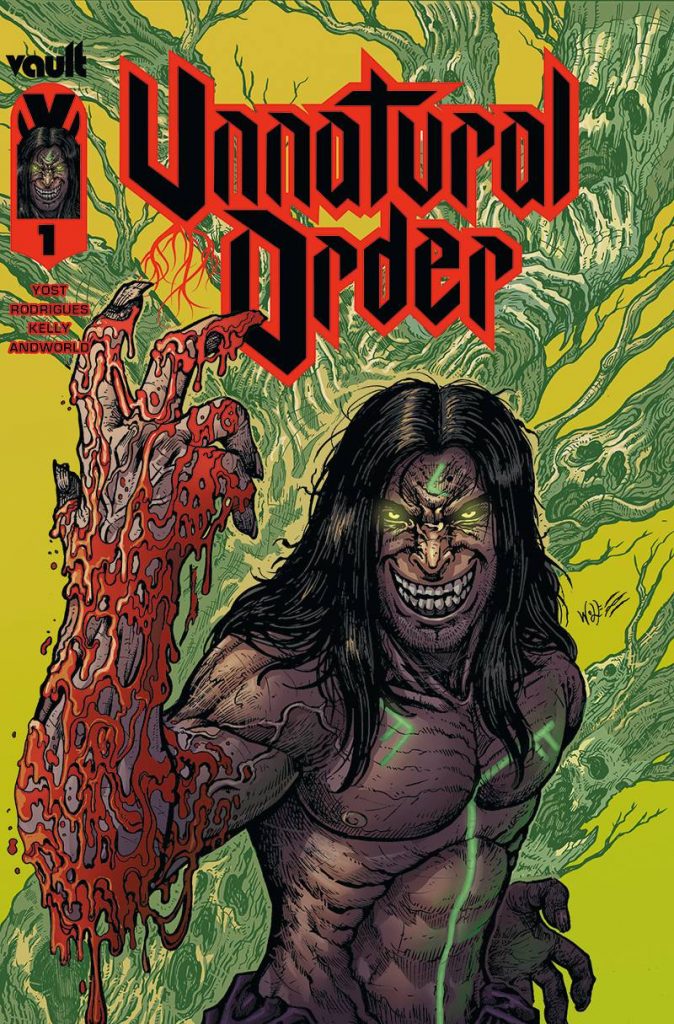

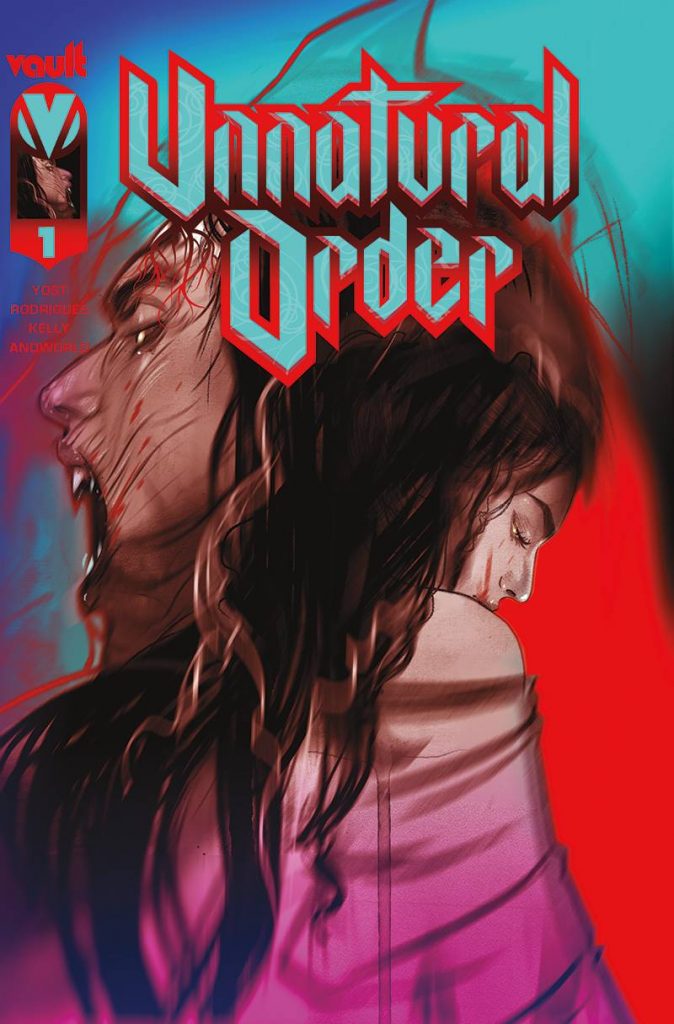

I did want to mention the variants part of this because that’s one side I don’t totally grasp. So, the free comic is the A cover. It’s the main one from Val Rodrigues. There are variants from notable variant artists, including I believe Tula Lotay and Maria Wolf. Those were open order. They were not incentive, but they had a slightly different approach. How does that factor into this?

Damian: The thought there was fairly straightforward. I know that collectors get a lot of flack from certain folks in the comics business. There are reasons that people find collectors troubling. I don’t necessarily agree with all of the reasons. I do understand from a shelf inventory management perspective why that may sometimes feel frustrating for a retailer. I’ve been told they exist, but I’ve never met a collector who is not also a reader of comics. I’ve never met a collector who isn’t also an extreme evangelist for the medium.

Collectors have been big supporters of Vault for many years. We want to make sure that there’s inventory in the market that excites them. The inventory in the market that excites them has to come with some measure of scarcity, otherwise they don’t get excited about it, for obvious reasons. There are a few different ways you can enforce scarcity. One way to do that is with incentive structures. Another way to do that are limited print runs. Those aren’t really ways that help the vendor benefit from the collectible market in any way.

They don’t create financial events of any kind for the vendor. So again, I sort of came at this problem in a mathy way. (laughs) “Which parameter can we move where there’s potential upside for us if these are also exciting titles in the collectible side?” And the answer there was the price point. If we eliminate any other tool for creating scarcity but price point, then the titles will probably be ordered directly proportional to their price. That’s more or less what we saw. A fairly predictable curve based on price. The more expensive titles will be rarer in the market.

I can’t speak to whether the collectors will be proportionately excited as the price point goes up, but what I can speak to there is retailers will be incentivized to create pricing on those that creates margin for them, but we’re also benefiting from that margin. It’s silly to get frustrated about it, but the frustration happens because businesses are run by humans, not computers as of this point in time. (laughs) When you see a title that you’ve tried to structure as an enticing collectible performing really well in the secondary market, and you’ve sold this for standard retail discount off cover price, it stings a little bit every time.

And so, we were also asking ourselves, how do we avoid that sting? And then at the end of the day, we’re giving retailers a copious amount of free inventory. This is an opportunity for them to also purchase product where we do have margin and sort of balance out that program a little bit. It’s an opportunity for them to say, “Okay, they’re taking a big risk. We’re going to de-risk it a little bit here.” And so, all of those factors added up to how we took that approach.

I can’t speak to how this will work in the fullness of time. I don’t know what the numbers are going to look like on Beyond Real, for example. But I think that this has already proven to be a more fruitful, limited cover structure for us than the conventional incentive cover approach has been. And I’m sure you’re aware historically we mixed returnability and incentive covers and that the math on that gets dicey.

Yes, it does. I believe Diamond got rid of it for a minute just because it was so dicey.

So, you have the curve of buying, but also the curve of prices in terms of the variants. Did that help offset the free part?

Damian: Yes. I mean it was a meaningful chunk of revenue from that. That certainly helps offset the free part. That was very much a part of what we were thinking about with this, but it helps offset the free element in a way that is opt-in for retailers. Nobody’s forced to buy any of these. And it’s a way for customers too, because nobody’s forced to come along and buy the variants. We hope that they will. That’s great for the retailer and it’s great for us if they do, but we’re not strong arming anybody into supporting the initiative in that way. And in no way is that tied to how we’ll allow retailers to order the product in the future. And look, we had retailers order median numbers of bundles and go ham on the premium variants.

They know their customers, right?

Damian: And we had retailers order maximal numbers of bundles and barely order the premium variants. And we’re very happy to see both of those show up. This is actually a situation where it was hard for us to identify in the data any kind of typical behavior correlating between how many bundles a retailer ordered and how they structured their incentive orders. There were some retailers who ordered a good number of the free bundles, and then they ordered just one of the most expensive premium variant. They know what they’re after.

A key I’m sure you’re well aware of, but the key for anybody reading this to remember is this battleground has yet to play out. This comic is not out yet. We’ll still see what the results are when it arrives. But in theory, the funny thing about this is it’s one of the rare plans that seems to maximize readability and collectability at the same time for a #1, which is very tough to do because normally they’re kind of in conflict, to some degree.

I mean, think about incentive variants. There’s the 1:1,000 variant where you get a thousand regular comics that you probably are not going to sell so you can sell one really expensive comic on eBay for a big chunk of money to offset that, or at least you hope you do. And that is just a really good way to kill a lot of trees. I don’t know if that’s necessarily a great way to create readership. And it seems like it’s core to the plan that it favors both key markets, readers and collectors. That probably is why you want to do this again with Beyond Real #1. How did you decide to do it again so soon?

Damian: I’m a creature of spreadsheets.

I’m gathering that. (laughs)

Damian: I spreadsheeted this out multiple times and looked at historical ordering data and tried to create some predictive models for what a floor and ceiling could look like for this sales initiative, and then structured a prediction. This would be how many we would have to sell for this to feel like it was worthwhile and to continue doing it. And we put as much elbow grease into communicating this to the retail environment as we’ve ever put into anything.

That may contribute to the outcome, but the outcome was that we substantially outperformed that target, and so in virtue of substantially outperforming that target, we made two tentative conclusions that the retail environment really, really liked it and that we could do it again. And so we figured we would do it again. And look, doing this multiple times comes with some pretty obvious positive externalities. When we have that much product in the world out there on shelves in people’s faces, it’s now a marketing spend too, as it were.

It’s now a brand awareness play. It’s now a shelf space play. It’s now retailers have the inventory, they have no reason to strip cover return it because there’s just nothing there for them to get back. (laughs) They didn’t have anything to spend in the first place, so they’re going to keep pushing it. And look, there are shops in the country that already do that, that don’t return anything and make sure they’ve got shelf copies, 12 issues deep of #1. Those shops, as far as I’m aware, are crushing it because customers come in and they get whatever they want. This is also a push to make sure that availability of product is maintained for a product line.

You brought up the B2B stuff earlier. It helps to have that visibility both in shop and in The Hollywood Reporters of the world. You can now point and say, “137,000 copies. Boom.”

The big question is, how do you make this a sustainable plan? Because one of the tricky parts about this is there’s several places you could get caught up. Like, what happens if Unnatural Order #1 doesn’t move for shops? Or what happens if this becomes the plan rather than a plan? Will it work if it’s the only thing you do? I don’t know, but that is a big question. Is this something that you think will be a constant part of your playbook or is it all situational and you just have to find the right place to deploy it?

Damian: The answer to that is evolving as we evaluate the data. With that said, if this works in what we regard as a baseline, a worst case success, this is something we expect we’ll continue a lot of. If we fall below that worst case success floor, then we have to reevaluate. If we exceed the worst case success floor and we end up in some kind of median or high level success scenario, then this is probably something that candidly we’ll be expected to keep doing. Right? If it works really well for us and really well for the retailers, then we’ve duct taped ourselves to the mast on that one. We can’t walk it back if it’s working.

You wouldn’t want to though.

Damian: Retailers get really upset when you do that. (laughs) Understandably so. For us, we definitely plan to continue using this at key moments. How frequently we’ll use it is going to depend on a number of things. But I’m not going to say much more about this at this point because we’ll be pushing more out about it soon. We’ve got a whopper of a 2024 coming in terms of who we’re working with and what’s on the slate. There are a lot of opportunities where I think this can be extremely impactful for us, for the retailers, for the creators as we move into 2024. And the timing on this was non-accidental. We were thinking about ways to differentiate ourselves from other players in the landscape as we move into what I think is one of our most promising years of catalog yet.

Free #1s is definitely a good way to differentiate yourself. I have one last question though. You brought up an important word. Creators. I just interviewed Christopher Yost about Unnatural Order. It’s going to be up by the time this goes up. He seemed very excited about the plan. I doubt he would be that excited if he wasn’t insulated from risk. Is that a core part of this plan? You want to make sure that the creators you work with are taken care of regardless of the results of your mad science?

Damian: I think Yost thought about the risk element a lot more for his co-creator Val than he did for himself. We made it clear to Chris and Val, and every other creator that we’ve talked to about this, that their page rates aren’t affected by the performance of this initiative in any way.

And we’ve had lots of creators come to us in the wake of the Unnatural Order announcement and say, “Can we do this with my book, too? I don’t care what that means for the backend. I am really excited about the impact. I want that market presence. I want that level of excitement around the title that I’m creating.”

Ultimately, as I mentioned earlier, the goal here is to create something that is better from a gross margin perspective at the end of an arc, after the subsequent release of a trade, than the model that we have all historically been assuming is the only way to do it. The goal is to create a better bottom line for the title in the long run, but in no case will there be a worse bottom line for a creator.

I do think that part of the reason why creators are intrigued by it, besides the fact that anytime you see six-digit order numbers, you’re probably pretty excited about that, is it goes back to your two points. The scale and the risk. Particularly the risk. It’s very, very difficult to be given a shot in the current state of the direct market. This gives your book a shot to get in people’s hands, and that’s a big deal.

Damian: You asked earlier how long I’ve been thinking about this, and I said the answer was five years. And among the things I’ve kicked around in that five-year window are trying to evaluate how this could be good for everybody and really think through the angles on that and try to think through as well, suppose that we end up in a below success scenario. Does this make this worse for anybody? And the reality is no, right? (laughs)

If you imagine that you’ve got two titles in the comic book direct market, one title that’s performing at the upper end of typical for an indie comic and one title that is performing like Unnatural Order, and they both have typical attrition curves, or say the second one even has a more than typical attrition curve. If we run those out over time and we end up in a place where we’re talking about a book that is marginally profitable.

Say you look back at that. Which one is better overall for the creator, the one that had this huge media impact and huge reader access impact or the one that operated at typical independent comic scale? Which one was better for the retailer? Which one was better for us? The answer is the latter approach. And so, we decided to give it a shot to see if we could prove that out.

If you enjoy this conversation, please consider subscribing to SKTCHD, as the site and the work I put into it is entirely funded by subscribers.

For reasons we’ll talk about soon.↩