Bringing Dirtbag Rapture to Life

Let’s get really, really, really into the weeds on how comics come together, with a current Oni series as our focus.

Once upon a time, comics felt like magic to me.

Each Wednesday like clockwork, comics just appeared in my local comic book shop for me to read. And that would happen again and again, into infinity as far as I knew. They were willed into this world through some means, I thought, all for the enjoyment of fans like myself.

That was when I was a kid. Thankfully, my understanding and appreciation of the process of making comics has expanded since then. I now know that it isn’t magic that turns an idea into a staple-bound story in a comic shop on a Wednesday, 1 but hard work, collaboration, and, quite often, well-established processes related to the production and distribution of comic books. While I suspect most fans know that these days, 2 a comic’s journey from genesis to a physical object in a reader’s hands is largely understood in broad strokes rather than with any specificity. Yes, people make these comics. But what of the details along the way? The nitty gritty elements that didn’t just happen, but helped shape the tale that was being told?

Those might not be as fully known. For that reason, exploring each step of a comic’s path became something of great interest to me. It might not just be a fun story, I thought, but a useful one for readers who aren’t fully aware of just how arduous and complicated the experience can be.

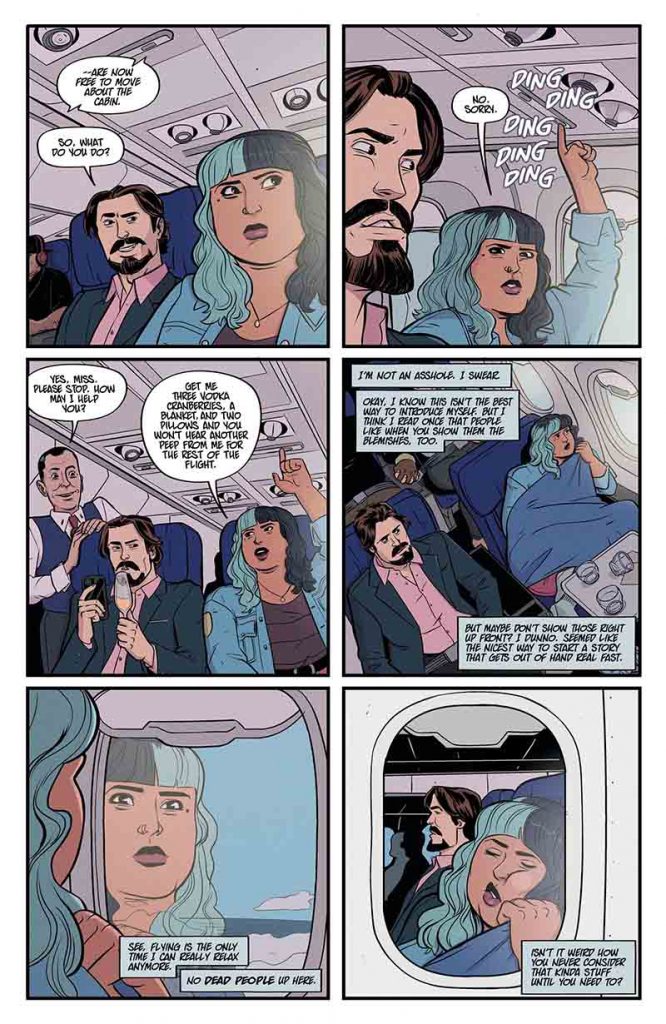

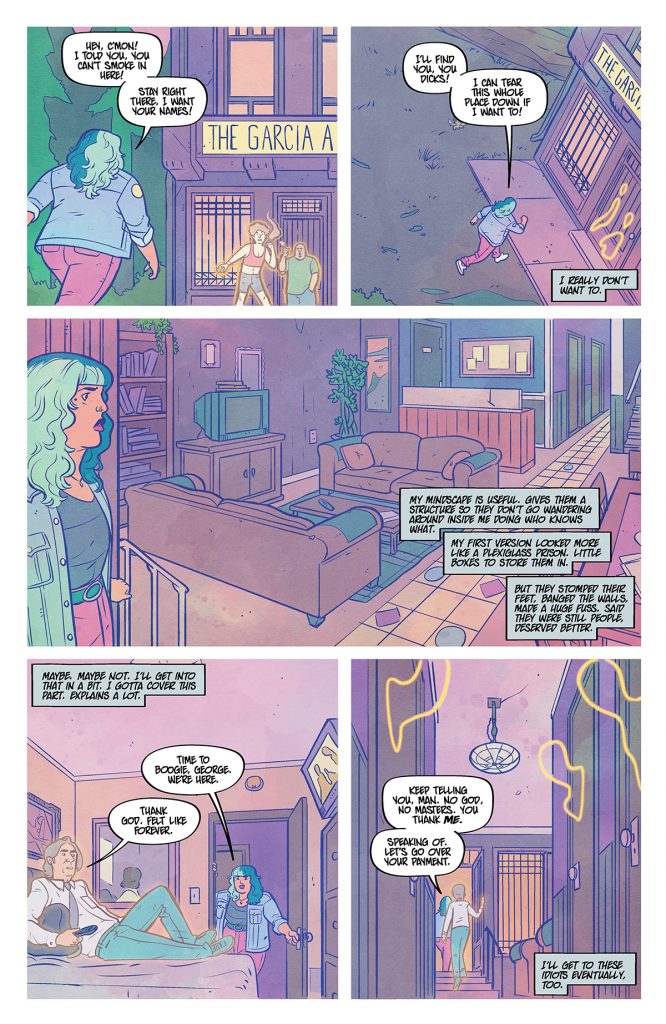

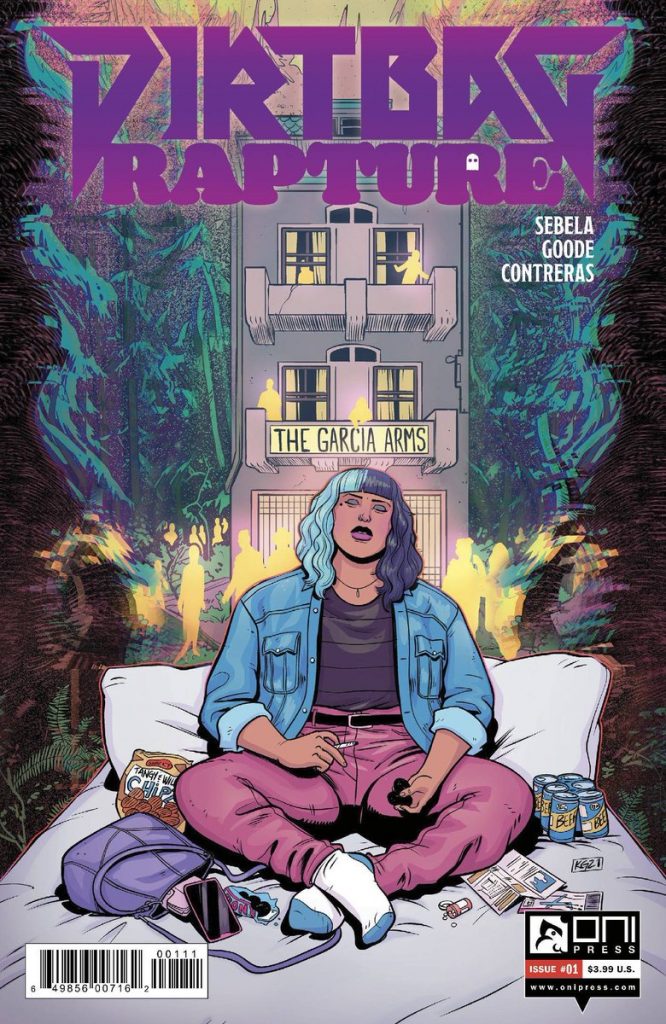

With that in mind, I talked with people behind one of my favorite new titles from 2021 – Dirtbag Rapture by writer Christopher Sebela, artist Kendall Goode, colorist Gab Contreras, and letterer Jim Campbell, a mini-series about a woman named Kat whose near-death experience allows her to communicate and engage with ghosts, putting her in the middle of a long conflict between angels and demons – over the last month and a half to explore the act of making a comic, from concept and creation to processes and production.

We’re going to be getting into the weeds on bringing this series and, in particular, the first issue to life. The hope is that with this, we’ll all better understand what it takes to create a great comic like Dirtbag Rapture, and how it isn’t magic that brings us our faves each Wednesday, but a group of talented individuals, a ton of work, and a whole lot of time.

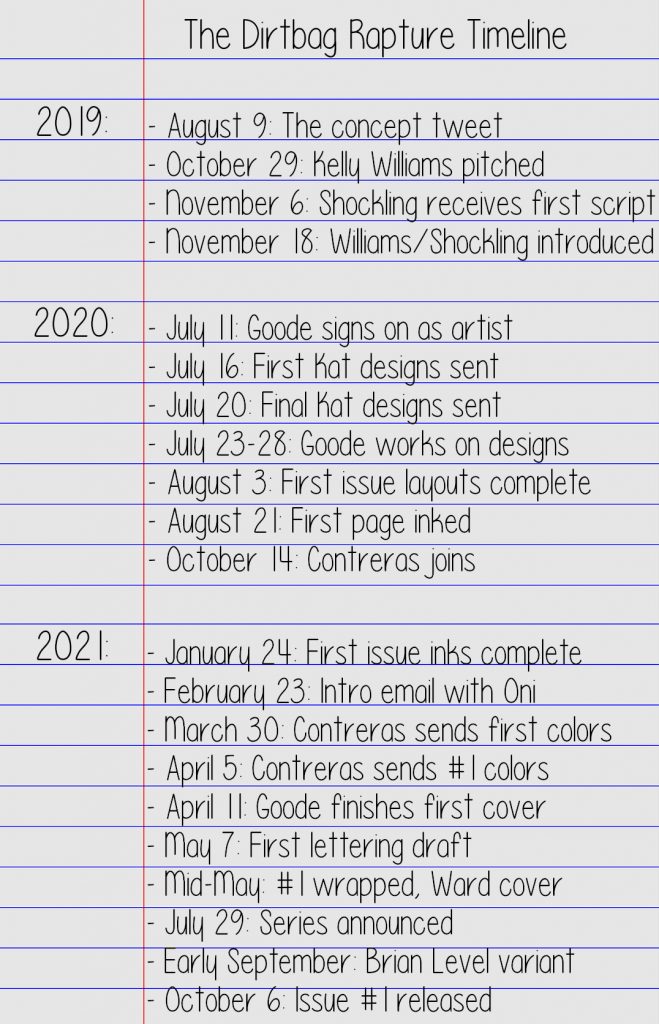

We love to romanticize the origins of ideas. It’s understandable. To the readers of stories, coming up with an iconic concept is mystifying and beyond comprehension, simply because it’s something we don’t do. And sure, sometimes they come to a storyteller in a grand, unforgettable moment. But in my conversations with creators over the years, the majority start in the most ordinary of ways. Take Dirtbag Rapture as an example. It all started with a joke tweet Sebela sent off while at a coffee shop back on August 9th, 2019.

Now, most tweets are fired off in haste and forgotten even more quickly, unless we’re cursed with the experience of going viral. Something about this one stuck with Sebela, though.

“I made the tweet,” Sebela said. “And then I remember leaving the coffee shop and walking down the street and thinking, ‘That’s a really good idea.’”

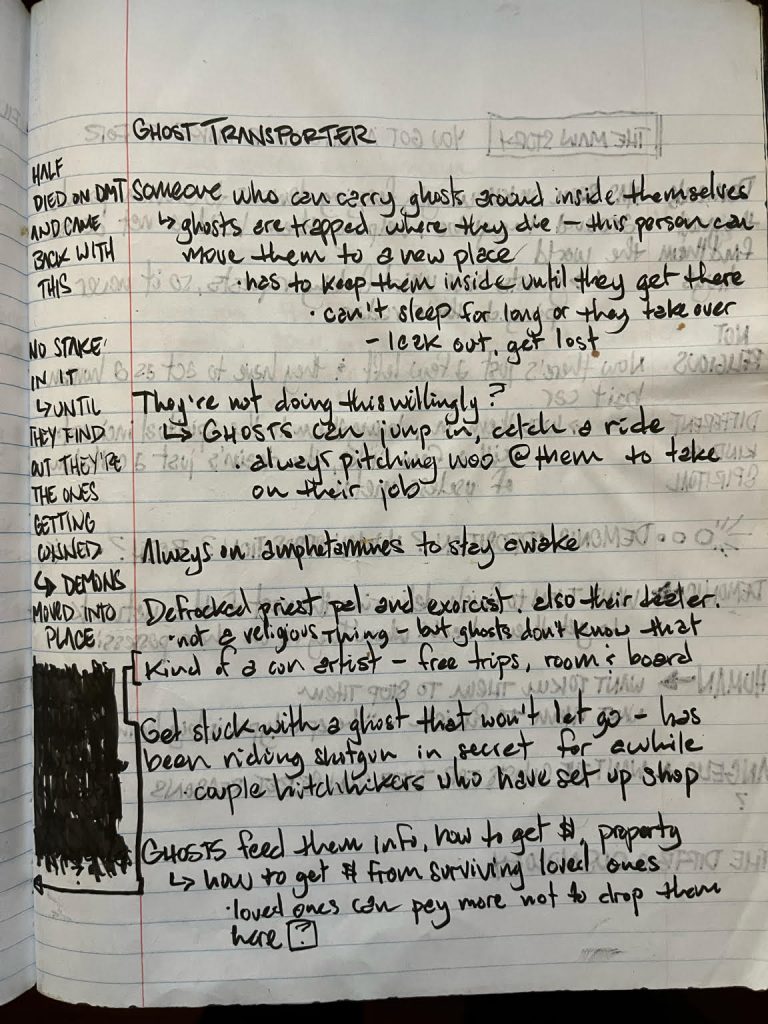

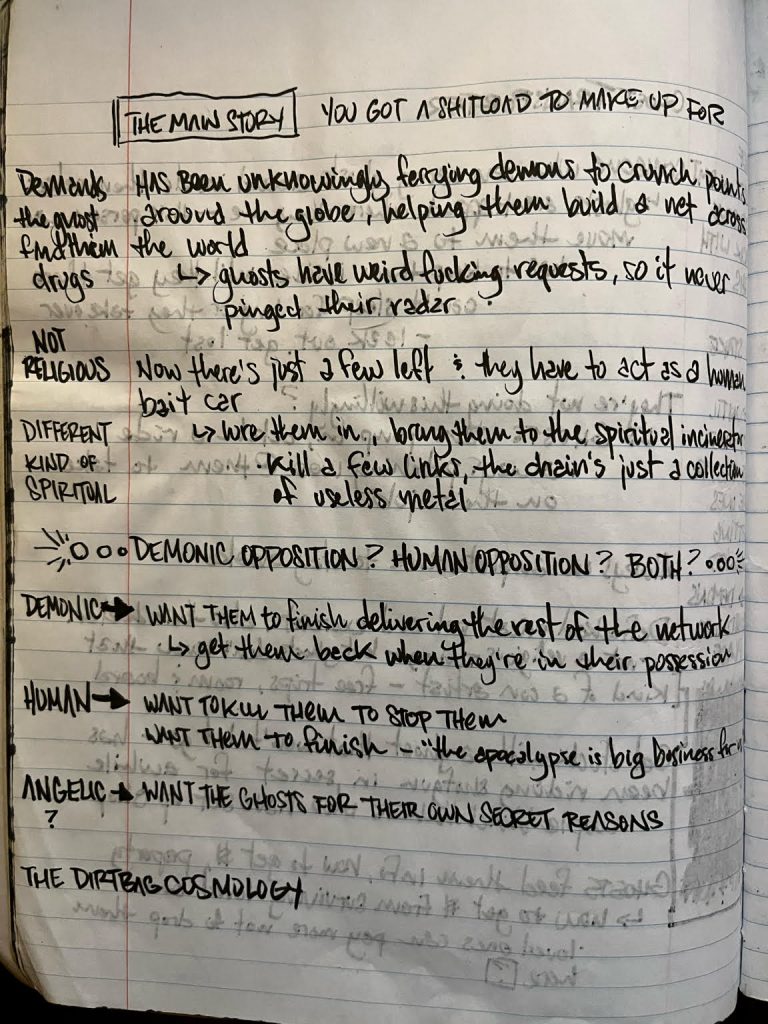

The writer followed his usual process for an idea that sinks its teeth into him: he moved it into his Woodshed notebook. This notebook is a “proving ground” for premises that enter his brain. The idea behind it is simple. He gives himself a page, front and back, to test the concept. If something meatier comes from it, he elevates the idea to its own notebook.

“If I can’t find anything interesting in 60 lines of notebook, then it’s probably not very good,” Sebela said.

Dirtbag Rapture’s notebook entry starts with the words “ghost transporter,” but by the back half of its test, the scribe had built out the conflict between demons and angels that’s at the core of the story. He even had the roots of the comic’s title in there. Originally, the series was called “Dirtbag Cosmology,” but he later decided to tweak it when he asked himself, “Who the fuck knows what a cosmology is?” The word “rapture” did show up soon after, though. 3 That was enough. The title eventually known as Dirtbag Rapture got its own notebook.

Things moved quickly from there. By early November, Sebela had contacted two potential collaborators to work on the project. The first was artist Kelly Williams. Sebela sent Williams the pitch on October 29th, 2019. The artist was into it, so step one was done. With the project’s notebook shaping up nicely and Williams onboard, the writer wrapped up the first script. On November 6th, 2019 – or just little under three months after the tweet that inspired it – Sebela sent a full script for Dirtbag Rapture #1 to his friend and “first sounding board,” Andrea Shockling.

“I just needed somebody to tell me I wasn’t crazy and that this was actually something good,” Sebela told me. “She gave me notes two days later. She was the first one to really confirm that this was an actual good idea.”

From there, Shockling was introduced to Williams on November 18th, and shortly thereafter, the team began to work on pitch pages. Those were coming together quickly, as the team wanted to nail down the pitch before involving publishers and other collaborators. A big thing for Sebela is he likes to have the first five to seven pages finalized to use for a pitch. The reason for that is that “you’re already ahead of the game” if and when a publisher says yes. The team was on its way to the next step. Things were looking good.

If you’ve read Dirtbag Rapture, or remember the credits I listed before, you probably have questions in your head about those names. That’s for good reason: neither Williams or Shockling worked on the final release. Shockling couldn’t stick with the book, but she had a real impact on the title’s early days. Her contributions are ones Sebela wants to highlight eventually, as he hopes to get her credited when the trade drops. As for Williams, the artist had an opportunity with Mad Cave Studios pop up in the middle of 2020, 4 which meant he would be tied up for the next year or so. Given Dirtbag Rapture’s momentum, Williams dropped off so Sebela could find another artist.

Goode was high on Sebela’s list of potential collaborators. More than that, the writer thought the artist had the right sensibilities for Dirtbag Rapture. At this point, Sebela knew he believed in the project and “had all this extra money” thanks to staying home throughout the pandemic. So instead of just asking Goode about pitch pages, he made a bold decision about the path the pair could take if the artist signed up.

“I was like, ‘Let’s just do the whole first issue and then we’ll find somebody who wants to put it out,’” Sebela told me.

Per Goode, Sebela sent the pitch and first script over on July 11th. Goode found a lot to like. The artist enjoyed Sebela’s work, thought the concept stood out, and was totally hooked by the end of the first script. 5 He said it read “so clearly in my mind,” as if it was “a movie happening in my head.” This was rare for Goode, at least relative to the usual pitches he gets.

It certainly helped that the project offered both instant action and immediate payment. Being able to jump straight into drawing the first issue without Kickstarting it or finding a publisher appealed to Goode. He was onboard pretty much immediately.

While they were eager to get into the issue itself, the first step was building the world. And it all started with the title’s lead, Kat. Interestingly, the character had already been designed once by Williams. Goode didn’t want to know anything about that, though, preferring to go in blind and work off Sebela’s perspective on the character. The artist didn’t want anything about the origins of the work to be murky, so he decided early on “to create this on my own,” avoiding all of Williams’ initial visuals.

Goode said Sebela mostly offered character insights, leaving the design to him. The one real visual suggestion the writer made was that he didn’t want the character to look like a “typical” lead – Sebela specifically said he thought “she should be bigger” – which fit Goode’s desire to not just draw “idealized” versions of people. Goode got to work after that, with his first take pretty much matching what we see in the book, save for the artist’s early plan to give her curly hair. 6 Sebela remembers seeing that first design – which Goode sent on July 16th, just five days after initial outreach, before being finalized on the 20th – and thinking, “(Goode) completely gets it.” While he liked what Williams came up with, this was the Kat he wanted, and it wouldn’t have happened without having to begin again with Goode.

“As frustrating as false starts and comics can be, it’s nice sometimes to have them to give you a chance to reconsider the choices you made before,” Sebela said. “I think it definitely paid off here.”

After Kat was finalized, Goode got to work with the rest over the rest of July. Much of those early days were about “drumming up ideas.” Some of that was building out major details, like the dreamscape in Kat’s head where ghosts literally take residence in an almost metaphysical hotel called The Garcia Arms, or how the angels and demons from the book looked. Other aspects were smaller, like Goode’s decision to depict characters possessed by an angel or demon as “sweaty,” both to aid readers in understanding what was going on and to underline the impact of possession on a host. Regardless of the significance, this design work led to rebounding energy between the two creators. As Goode told me, “I think (Sebela) liked the designs enough that when he was writing, he went off of those ideas.”

While some of the ideas were created before diving into the first issue, the artist told me “a lot of the design just kind of happens on the page.” Goode found answers as he worked on the first issue, a process he said took longer than he hoped for because he was “dragging (his) feet a little bit” for reasons he couldn’t quite explain. 7 While he finished layouts for the first issue on August 3rd, 2020, he didn’t wrap inks until January 24th of 2021. He was concerned during that stretch that Sebela was frustrated about how slowly the project was coming together, but the writer later told him that the process on Dirtbag Rapture was actually a lot quicker than usual.

Sometimes overthinking things happens, even with comic creators.

The next person to enter the picture was colorist Gab Contreras. Sebela knows where his strengths lie, so he let Goode take the lead in determining their collaborator on that front. Another artist recommended Contreras, a Peruvian colorist whose work stood out because of her simple yet effective approach and the unique look to her work. This wasn’t to get Contreras started immediately, though. Per Goode, “Chris wanted to make sure we had a colorist ready to bring on the book” to ensure a quick start once they had found a publisher. With that in mind, Sebela reached out to Contreras on October 14th, 2020.

Conteras told me it was just a pitch at the time, only moving on to full production months later. But she accepted it the same day. She liked both the team behind it and the “spooky and funny pitch.” It was an easy sell for the colorist.

Two became three. Now, Dirtbag Rapture just needed a home. With a fully inked first issue in hand and discussions already happening with Oni, it was a similarly quick pitch for the publisher. Editor Jasmine Amiri, who initially co-edited it with her fellow editor Zack Soto before he stepped off the title, 8 found it appealing from the jump.

“It’s just such a unique, interesting book,” Amiri said. “I think a big part of it is the main character. She’s just somebody I would love to see more of in comics just across the board. Also, the concept is bonkers, especially when it comes to life and death and ghosts and angels and demons and all this stuff. It’s amazing.”

Amiri loved the creative team, and was particularly thrilled to team with Goode again after working on a rushed Maze Runner adaptation with the artist before. She wanted to see what he was capable of in a better situation. The team was hard not to love for any editor, if only because they were pretty far along “compared to where most projects are when we first start them,” Amiri said. With the first issue scripted and inked, everyone was able to skip several steps in the usual process. Amiri and Soto’s big tasks were digging into the outline of the series Sebela put together before meeting the rest of the team.

That introduction happened on February 23rd, as Goode and Contreras met the Oni team via email. There was still one more member of the team to sign up, though. The book didn’t have a letterer. Sebela briefly tried lettering the project back when Williams was the artist, but reality struck during the attempt. He said he realized, “Boy, I really suck at this” and decided against it. Sebela turned to Oni, and Amiri came to the rescue. Or, more specifically, one of her most frequent collaborators did.

“Honestly, Jim (Campbell) is my go-to. He’s on probably 90% of my books,” Amiri told me of Dirtbag Rapture’s letterer. “I’ve put him on so many different types of books and it doesn’t matter if it’s horror or a slice of life romance, he’s just always on top of the style.”

The appeal for Campbell was multifaceted. He had wanted to work with Sebela again after teaming up on We(l)come Back at BOOM! before, and the letterer knows and trusts that Amiri would never lead him astray. Seeing the work Goode and Contreras were doing only made that easier for him. He was in.

With the team together, it was time to finalize that first issue. Again, they had a massive head start, as it was already written and inked. But there’s still a process to be followed. The first was establishing how they’ll communicate. In short, the entire team – creative and editorial – was on a massive email thread together. Amiri said that isn’t necessarily typical or atypical. It just fit the nature of the team. Sebela, Goode and Conteras came in together and Campbell was added on. As she said, “it just made sense to have everybody talking” so everyone could build off notes to one another. Amiri emphasized how important communication is to the overall process of making a comic great.

“So much of (making comics) is just creative conversations, whether you’re talking with a writer about the story or the art team about what they want something to look like or how they’re going to design a certain character,” Amiri said.

It also aids the project management process and ensures everyone is both happy and having fun. As she noted, even that aspect was easier than usual thanks to the project’s advanced nature – a lot of that was due to Sebela, who tried to give the whole team “as much information right up front” so they were all on the same page – but the team was always sharing entertaining details with one another, like Goode and Contreras hiding the It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia cast in the background. That thread was where much of the communication took place.

Not all of it, though. Contreras is big on collaboration during the comic making process, saying, “If I have the chance, I always tend to have close communication with the artists to get extra feedback during my coloring process.” She and Goode worked closely throughout, except their communication took place via Discord. The colorist would send the artist pages for feedback over chat, just to get on the same page about her choices. Once they agreed, Contreras would drop the pages in the email thread with editorial feedback coming from there. But the pair always communicated first, even if it was important to Goode to “let Gab be the artist for her part.”

“I’m not going to art direct a colorist,” Goode said. “She’s done the work. She knows how to color.”

To assist in her process, Goode sent Contreras colored designs of the cast as guides, as well as “a reference folder with images of some objects and locations,” according to the colorist. From there, Contreras worked off the script and the inked pages, determining the palette and mood for the story, as well as figuring out how to differentiate the mindscape scenes and how the ghosts would look. Communication helped there, as she said she “received some good feedback from everyone on the team,” ensuring “we were all happy with the finished result.”

It came together quickly too. Contreras initially sent colored pages to Goode through Discord on March 30th, 2021, before finishing issue #1 a week later on April 5th.

In a lot of ways, her job and Campbell’s aren’t altogether different. Campbell described his approach as “gauging the tone of the story and the look of the art” to determine a style that meshes well, which sounds quite a bit like Contreras’ process. And instead of communicating primarily with the line artist before going to the group, he worked directly with Amiri, a method he described as “par for the course.”

There was one other key creative element: the covers. Oni debuts come with both an A cover and a variant, or B cover. The former was by Goode, something he wrapped on April 11th. He wanted it to be “an element of the story and of Kat,” as he endeavored to combine key aspects of the title like the mindscape and The Garcia Arms into the image. It’s a good one, both as an impactful piece and one that’s reflective of the story overall.

Variants are a core piece of the direct market puzzle. They “really help with sales” according to Amiri. And if you get the right artist, they can fit the vibe as well. Initially, Christopher Cooper, someone Sebela recruited, was going to provide the variant. But he had to drop out for personal reasons. Once that happened, the team had to move quick because of where the book was. Soto already had a pitch in with Malachi Ward so he checked in with the cartoonist about providing a piece. He turned out a stone cold killer of a cover by the middle of May. It was a perfect, unexpected solution to the variant problem, even if Amiri’s dream of turning “it into one of those blacklight weed posters” didn’t come true. 9

The team was thrilled about the process of putting the first issue together with Oni. Sebela said they didn’t even balk at each issue being 24 pages, something he suggested most publishers wouldn’t support. It was what he needed “to tell the story correctly” and the team wanted to help him do that however they could. That story is a microcosm of the overall process. The team had a vision, and Amiri and the rest of Oni supported that vision throughout. Amiri said her biggest notes were on colors, particularly in regards to some of the more fantastical elements. But even with those, “Gab did such a great job,” the editor noted.

“They were really helpful with both guiding us and not getting in the way,” Goode said. “It was a really good collaboration.”

“This is one of those gem projects that come around every now and then where everything goes so smoothly,” Amiri said. “Everyone is just firing on all cylinders.

“It was such a dream and just incredibly easy to work on.”

The first issue wrapped when Campbell closed letters in mid-May 2021, slightly under three months after the ball started rolling with Oni. There’s not much left to do from there besides, you know, actually releasing the comic.

The way a direct market oriented, single issue series 10 like Dirtbag Rapture works is it’s announced and solicited for orders for comic shops three months before release. Math seemed likely to play a big part in when a title is announced, as you figure out a release date and then effectively subtract three months from that. But the process behind deciding these dates was an unknown. According to Sebela, it’s one that was largely up to Oni. 11 As he said, “They call the shots as far as that stuff goes, which I’m fine with.”

Amiri said there really isn’t “a set formula” for how and when something is announced. It was also more in Oni publicist Tara Lehmann’s wheelhouse. Lehmann described the process as having “a few factors,” with the biggest being “whether how we announce a project will be to the benefit of the creator, the title, and the readership” and how that announcement fits with the overall promotional cycle. Another key factor is how production is pacing. Announce too early and delays will hit because the work isn’t complete. Conversations with a title’s team are important for that reason, even if it’s more confirmation than anything. After considering all the factors, Oni went back to the creative team and said they were thinking October 6th for release. The team was comfortable with that. Everything was set, so the announcement went out on July 29th.

From there, the creative team did two things mainly: kept working on the rest of the series while promoting the title’s coming release, however they could. That mostly meant posting on varying social media platforms. Of course, Goode was correct when he said, “I can only do so much because social media is a game you can’t win,” but they still boosted it throughout. Sebela endeavored to try “to find ways to talk about it that weren’t obnoxious,” something he described as “tricky.” That’s part of the reason he likes working with a publisher like Oni.

“One of the benefits of going with a publisher is a lot of that stuff gets taken off your shoulders, which I’m always grateful to let go of,” Sebela said. “Because I’m still not very good at it.”

The writer said Oni came to him with a marketing plan that worked for him from the jump. 12 That approach, per Lehmann, was to highlight the work of the creative team to their existing readerships within the direct market, before looking “outside in the more mainstream space for readers who may have had tangential interests to the theme, story, and style of the series.” Lehmann added, “We always take the creative team’s view and vision into account while promoting,” but in this case, the team was thrilled for Oni to handle marketing the book.

The team at Oni is also in charge of taking the finished comic and supporting elements like covers and fusing it all together to make a finished comic for printing and distribution. That means getting a designer to create a logo – that was Dylan Todd, in this case – creating the inside front cover with the credits, developing all the backmatter in the comic, and then proofing it internally until everyone is satisfied. Once that happens, Amiri “puts in a request with the Oni production team to process all of the files” before “they assemble everything” to create a proof of the first issue. Another round of edits from the editors on the book and the managing editor come, and once the proof is approved, it’s sent to the printer.

“And then a month later, a book is on our desk,” Amiri said.

October 6th hits, and Dirtbag Rapture #1 is released both in comic shops and digitally. At that point, Sebela was almost done with scripting the whole series and the team was nearly wrapped with issue #3. While release day is still a work day, everyone agreed that you keep an eye out for the response a bit more when the first issue drops. Contreras and Campbell both believe that it’s rewarding to see positive comments about the title after all the work, with the latter saying it’s “gratifying” to “learn that people ‘out there’ in the real world are enjoying it.”

Amiri was eager to see the response as well. She said she was “just on Twitter all day long searching Dirtbag Rapture and seeing what people said about it.” Interestingly, she said she does that mostly for single issues, as they have a quick turnaround time in production. Collections and graphic novels have “such a long gap” that she tends to forget when they’re released.

Time is a funny part of the whole experience. It can warp your relationship with the work, like it does for Goode. The artist described release day as “a weird overlap” of timing. People were talking about issue #1 while he was already done with issue #3. Seeing his work from eight or ten months previous released in the wild can be a “disconnect” after mentally moving on from the work. It’s a good feeling, but a strange one.

As for Sebela, he told me release days are “not nearly as crippling as they used to be.” Earlier in his career, he was “completely useless” on them due to constantly browsing Twitter and ComicBookRoundup’s collection of reviews. These days, he’s found a better balance. He’s still “glued to social media,” especially with first issues, and doesn’t “get a lot done that day.” But he’s gotten to a point where the highs bring him joy without the lows weighing him down.

“I just sort of take what comes to us,” the writer said.

That could be the motto of Dirtbag Rapture as a whole. Despite being mostly developed and released during a global pandemic, with giant, unexpected roadblocks entering the picture throughout, most of the operation was smooth sailing. Sebela described the experience as “rare.” Most of the time you have “this sort of hooky concept,” he told me, it doesn’t become a fully fleshed out story quite so easily. He knows that all too well. He’s currently dealing with an idea he loves that has yet to escape the Woodshed notebook.

That’s why he says Dirtbag Rapture is “definitely an exception more than a rule,” making this look at the comic making process just one of many possible versions of how things could go down. It isn’t this easy quite often. But it could be with the right idea and the right team, as everyone involved with Dirtbag Rapture discovered over the past couple years.

Thanks for reading this longform feature. Pieces like this take a lot of time and effort, all of which are funded by subscribers. Want to read more pieces like this in the future? Consider subscribing to the site to support the work and to read more features going forward.

Or at least not exclusively magic.↩

Heavy emphasis on most. Some still act as if there is no human element to the process of making comics.↩

Sebela remembers he was set on “Dirtbag Rapture” pretty early because he talked about it over one of the last regular lunches he had with writer Matt Fraction before the pandemic hit.↩

This seems to be Bountiful Garden with writer Ivy Noel Weird.↩

Which is a great twist I don’t want to reveal, but it’s understandable that it did the job for Goode.↩

He decided that going with straight hair would be a lot less painful in the future.↩

I’ll explain it for him: it was 2020! We were all dragging our feet!↩

Co-editing is unusual for an Oni project, but they both loved it so they agreed to team up.↩

There was a third cover from artist Brian Level that entered the picture in early September. That one didn’t come up in conversations, but it definitely existed (and, oddly, was labeled as the D cover rather than C).↩

By the way, there was a brief discussion about making it into a graphic novel. Oni thought it fit better as a single issue series, per Sebela.↩

Which is pretty standard across all publishers, the writer shared.↩

Even if the one idea he loved had to be abandoned, which was getting Dirtbag Rapture branded rolling papers sent to comic shops.↩