So Long, Kaijumax, and Thanks for All the Megafauna

My beloved ends today. Let’s look at it one more time, with insight from its creator.

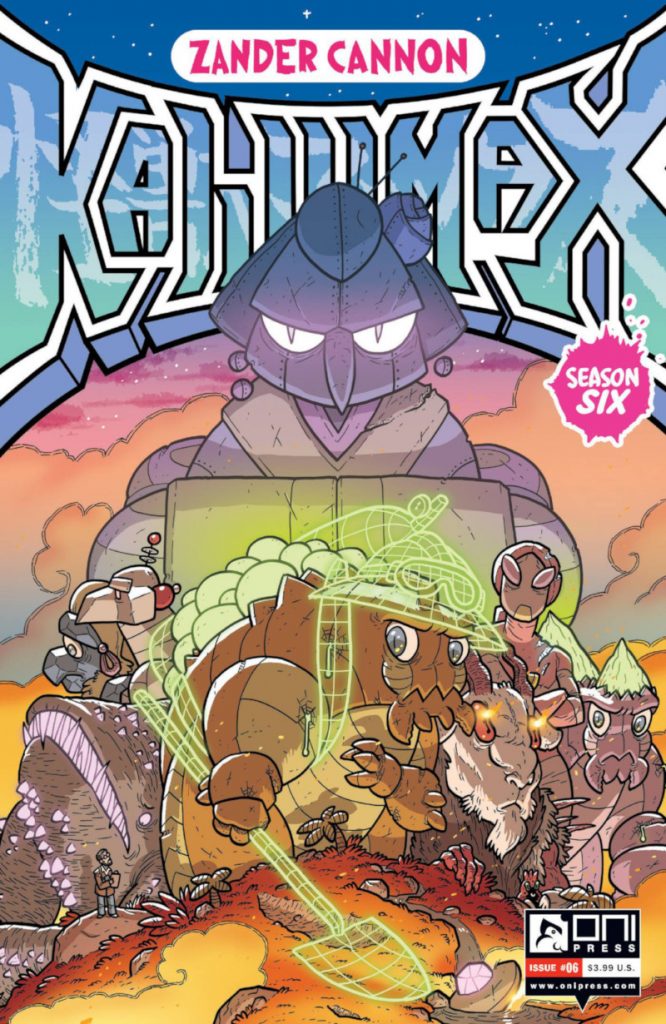

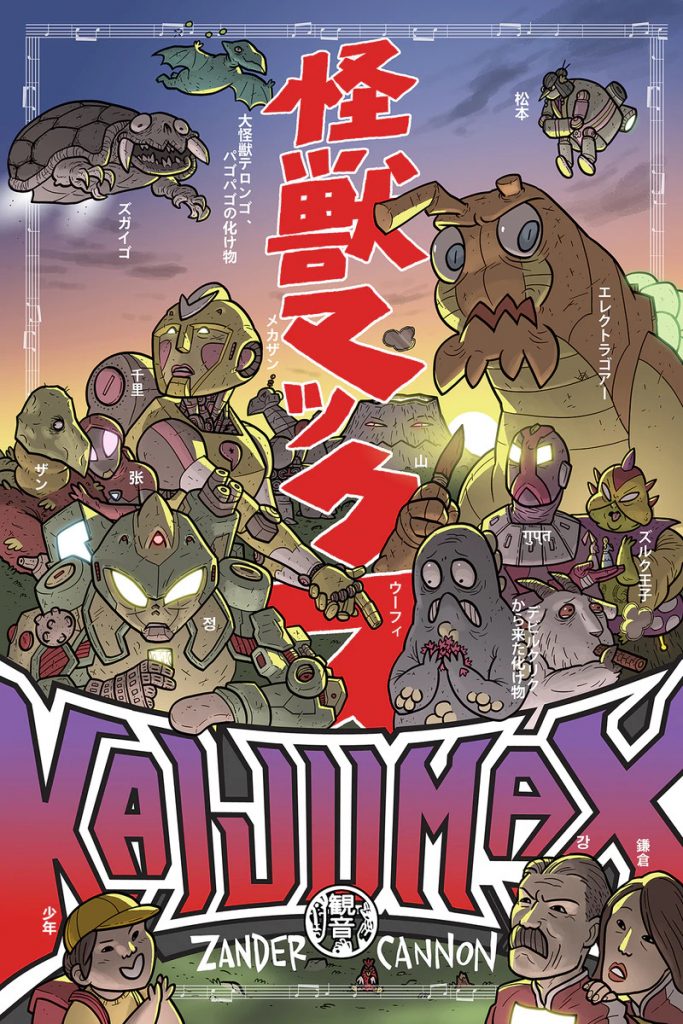

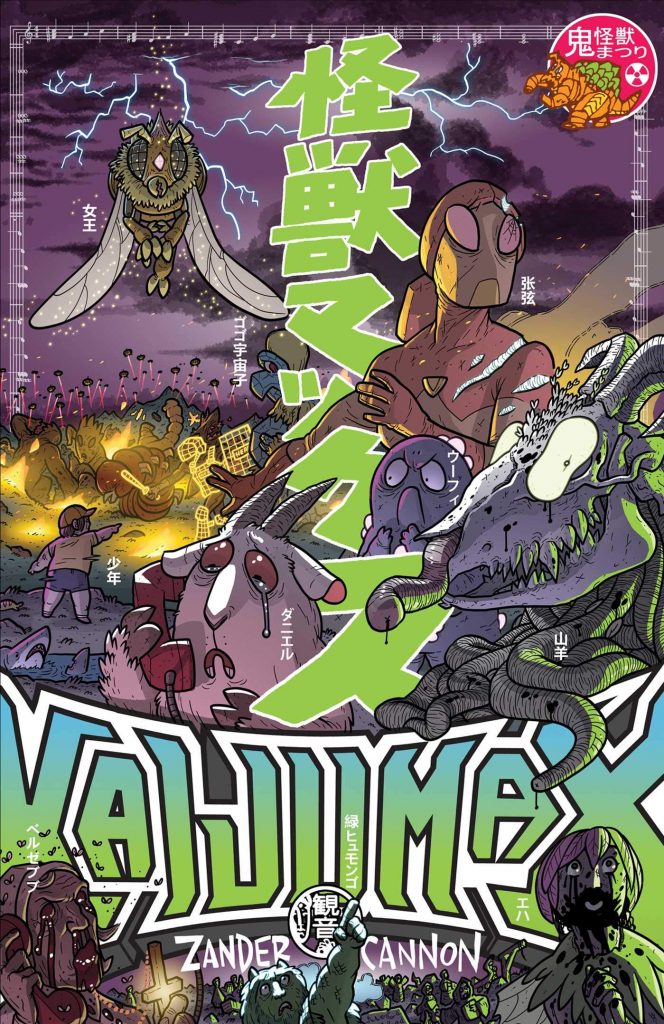

A new issue of cartoonist Zander Cannon’s magnum opus, Kaijumax — his Oni Press series that explores the lives of those who reside (and work) in a supermax prison for kaiju 1 — arrives in comic shops today, but this one is a bit different. It’s the finale, bringing the tale to its long planned conclusion. This would normally be where I’d tell you why this heartbreaking work of staggering genius (and kaiju/prison movie references) is worth a multi-feature celebration, but you’ve heard plenty from me already about what makes the series special. Perhaps too much, which I say knowing full well that there’s an entire feature still to come. But it isn’t just me that thinks the world of this series. Others had thoughts about why Kaijumax is so incredible before we get into the meat of today’s celebration.

“I was already a huge fan of Zander’s but seeing him tackling kaiju (something else I’m a huge fan of) was like peanut butter and chocolate! Two great things that are even better together,” cartoonist Chris Samnee said. “I fell in love with the art and the character design— but the world building is second to none. I’m sad to see it ending but so excited to see how he wraps it all up.”

“Everything?” cartoonist Ryan Browne answered when I asked him about what made the series and Cannon’s efforts special. “The connections he made between prison and Kaiju tropes are truly otherworldly.”

“The magic of Zander’s storytelling in Kaijumax is that he is able to juggle the absurd and the hilarious, but also level the reader with some devastating emotional turns that are entirely earned from a pure character level,” Oni Press’ EVP of Creative, Charlie Chu, told me. “For me, this book has been everything I love about comics.” 2

To like Kaijumax is to love Kaijumax; you’re either all in or all out. Unfortunately, as noted earlier, everyone is now all out. The series concluded with the sixth and final issue to its sixth and final season. I can confirm that it’s everything I wanted, somehow delivering both on that volume’s key arcs while giving readers satisfying conclusions for each of their favorites. That’s a tough line to walk, but one Cannon deftly balances.

Which is nothing new for the cartoonist. Over the six seasons, 36 issues, and seven years of the Oni Press series, Cannon has managed an astonishing balancing act, always finding a way to deliver a story that’s hardened yet hopeful, satirical yet serious, grounded yet goofy. It can make you think, mad, cry, and laugh in the same issue, all while investing you in its immense cast of archetypal kaiju and prison guards, even if sometimes you’re mostly invested in their demise. 3 It’s a remarkable achievement, and one I’m sad to say goodbye to.

Now that it’s finished, I wanted to give Kaijumax a proper sendoff. It is a remarkable comic, but behind the pages and panels some of us loved, there was Cannon, tirelessly working to bring an astonishing, absurd series to life. As the door closes on Kaijumax, let’s look back on its own story, with insight from Cannon on how it started, evolved, and concluded, becoming the best ongoing series of the past decade in the process. 4

Kaijumax began as a fusion of references as much as anything, growing from Cannon’s love of kaiju and prison movies as well as his consideration of what a marriage of those two might look like. To the cartoonist, it seemed as if it could be a potent pairing, and one he’d revel in. This wouldn’t just be him playing the hits, either. Cannon’s well of potential references ran deep, ranging from the most famous tokusatsu and prison works to insights he learned listening to related podcasts. He plumbed the depths to build up the idea and this world. 5

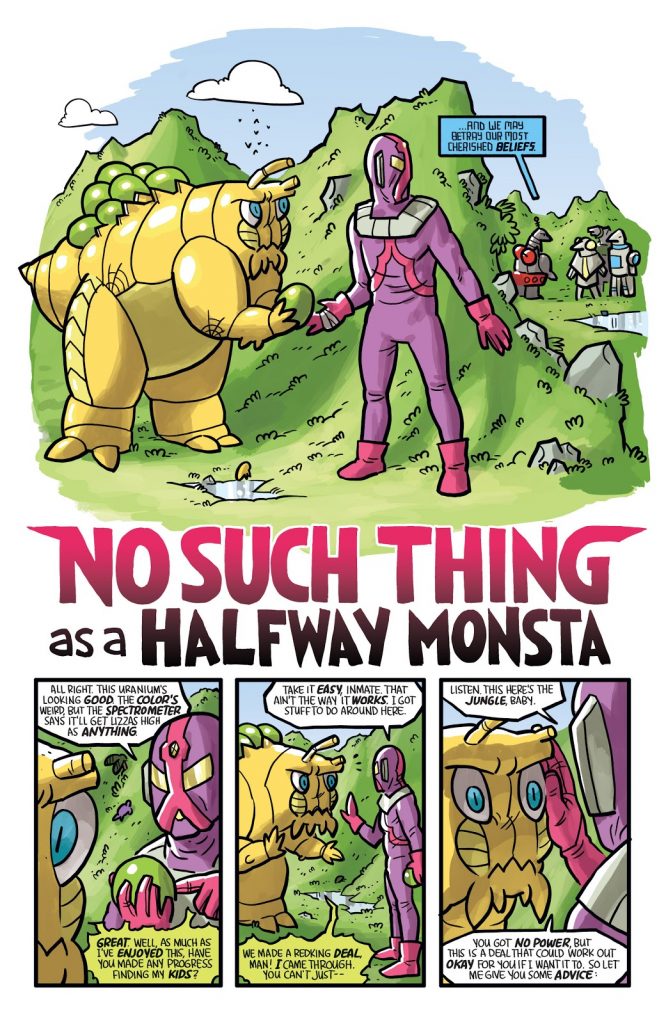

Series lead Electrogor was an ode to Godzilla, guards were typically Ultraman or Voltron/Power Ranger analogs, groups in the prison were often organized by origin stories, 6 there was a particularly famous joke from the first season in which inmates worked out by pushing over fake buildings, the bottom of the sea housed Lovecraftian parallels, etc. etc. Those are just a few examples off the top, but you get it. Cannon described these references as “a foundation” from which the story was built from. It was just a starting point, but one Cannon found to be a rich sandbox to play in as its sole creator, save for Jason Fischer providing color assists.

Looking at the series now, it’s impossible to imagine Kaijumax any other way. This exploration of prison life with kaiju making up its population and Ultraman-like super people acting as the guards is inseparable from all facets of Cannon’s talents as a cartoonist. His cartoony art style defined it, cutting some of the more intense beats of the series while delivering much of the empathy we have for the cast. But Cannon drawing it on top of writing it wasn’t originally part of the plan. The Kaijumax we know and love almost wasn’t a thing, at least not in the same way. That’s because Cannon wasn’t meant to draw it: Browne was.

Cannon pitched Browne about tackling the series at New York Comic Con in 2013 or 2014, with the artist going so far as designing characters and drawing pitch pages. 7 That version of the project was even approved by Oni. It seemed as if it was going to happen. The only problem was, Browne’s solo series God Hates Astronauts was picked up by Image at roughly the same time. Browne described it as a “tough choice” to move on from Kaijumax, but one that “certainly worked out for both of us.”

That’s an incredible What If…?, but one that seems to have played out perfectly, even if it might not have seemed like it at the time. When Browne moved on, Cannon admitted he thought Kaijumax was dead. Who could he get to draw it? That was when Oni came back and asked, “Why don’t you draw it?” He was skeptical at first, especially considering that he’d have to pay people to fulfill other roles on the book. Given its niche nature, that might be a drag on Kaijumax’s feasibility. But then he had a thought: maybe he could just do it all himself!

It was a lot of work for one person, especially considering that Kaijumax had a robust plan even when Browne was onboard. Cannon told me the series was designed to be “six seasons from the start.” The idea was he would do five or six issues before closing the season with a double sized special. Like with many things related to Kaijumax, that plan evolved. It shifted into a more straightforward six issue season, hold the double sized finales, presumably in part to prevent his eventual and unfortunate early demise.

The composition of those seasons also changed dramatically. Originally, the first season was meant to be a fusion of the events of the first two seasons, something that quickly stopped when the cartoonist realized, “Oh, there’s no way I could cram all that stuff in there.” The women’s prison storyline was supposed to be season three – Cannon even revealed that plan in the letters column! – and it originally took more from the 1970s film Caged Heat before it morphed into the more Orange is the New Black-like ensemble piece we read in season four. Certain beats moved from one season to another, if only to ensure they had the necessary space to breathe and become what they needed to become. Being the title’s only creator had its perks.

The beautiful thing about how Cannon structured the series, plot wise, was it gave him incredible flexibility to follow what spoke to him as a storyteller. A great example of that was the season four storyline of an inmate named Go-Go Space Baby, in which she had to give up the child she had in the prison for adoption. The baby was adopted by a “nice space superhero couple” 8 who lived in a galactic suburb called the Nebula of the Eternal Sunrise, perhaps never to be seen again. But Cannon knew there was more there, if he decided he wanted to go down that path. The storyline came back in the sixth season, and it proved to be one of its most heartbreaking, poignant aspects. That was his process for much of the series, at least outside the core storylines.

“I’d set it up and it was there if I wanted to use it, but I didn’t think about it until I was like, ‘What should issue #4 be?’” Cannon told me. “It’s nice to have options.”

That structural flexibility allowed for Cannon to work in whichever beats resonated with him the most, save for the main storylines. It resulted in a comic that was unpredictable, both for its readers and its creator at times, and a richer experience because of it.

Evolution was a constant theme for the creation of the series, something that fit its cast of monsters quite nicely. While that certainly manifests itself elsewhere, perhaps no aspect of the series shifted more than its tone. That’s not to say the early days of the series are unrecognizable to what it eventually became. It just naturally progressed from how Cannon originally envisioned it. It maintained its satirical nature, but the cartoonist “thought it was going to be a pitch-black humor book.”

“I did not really anticipate there was going to be a lot of sentimentality to it. I thought it was going to be, ‘Let’s jump in here, 50 million jokes and then get out.’ I thought it was going to be starker, harsher, in the realm of Rick and Morty where it would avoid all sentimentality,” Cannon said. “It probably would’ve been something that people would’ve described as edgelordy.”

There were multiple reasons this didn’t happen. For one, that very idea is antithetical to who Cannon is as a person. He told me as soon as he started working on the series – even when Browne was on it – he realized, “That’s not me.” While he still wanted to put together a series that was a cynical take on the prison industrial complex, he didn’t want it to be mired in cruelty or to lack a “counterbalanced moral arc for the characters.”

“I just wouldn’t enjoy it,” Cannon said. “I don’t think anybody else would either, or at least the people that I would want to enjoy it wouldn’t enjoy it.

The tone evolved because of that and his lack of desire to do something that was “a list of half-baked jokes.” While he wanted humor to be a part of it, “jokes will get you through six issues, no problem…but that’s about it.” He had to create stakes. To do that, he dug into the cast and concept, finding a fertile ground of emotion. That’s the space he prefers to operate in anyways. He shared that his writing tends to be “melancholy and emotional” naturally. But in this case, he viewed it as a necessary counteragent to the “grimness and cynicism of the process.” That this sentimentality was infused into a “cynical mashup” between monster and prison movies made it all the better, considering neither of those are particularly sentimental, as Cannon told me. That tension between sentiment and concept gave the title part of its singular flavor.

Some of that change in tone emerged simple because of how the world itself turned during the title’s seven years. In an alternate universe where things played out differently, maybe more of that black comedy would have made its way into the series. But the series “wasn’t exactly calibrated for the apocalypse,” Cannon shared. At least not at first.

“I think that because the world was falling apart, I felt like I wanted to give people a character to love, a moment to feel, or to have a moment of catharsis,” Cannon said. “I felt like that was important.”

It didn’t help that certain audiences embraced some of the more cynical or cruel aspects of the first season. 9 From that point on, Cannon said he felt as if he needed to be transparent about the type of story he wanted to tell and what he wanted it to represent.

“I do not like having any edgelordy fans at all,” Cannon said. “This was going to be a very much more sentimental, much less cruel comic than I was originally intending because I felt like I needed to make my position very clear.”

Even so, the series wasn’t for everyone, both by design and by nature. Early on, Cannon believed people understood the series was a mature readers series. But when some of the harsher beats from those early days hit, some readers turned on it hard. 10 The cartoonist thought it was a fair response. He even admitted that if he would change anything, it’d be how cruel the first season was at times. 11 But he was still surprised by how angry — and direct with that anger — people got.

It’s understandable to be taken aback by some of those first season beats – particularly Electrogor’s interactions with Zonn in the first season – but you’d be missing a lot of greatness by not continuing onwards. More than that, the tone shifts considerably, especially after season two. I’d even describe Kaijumax as a hopeful series overall, one that drifts considerably towards sincerity throughout its run. Cannon agreed with that idea, before noting that it still does have a lot of “grim stuff in it.”

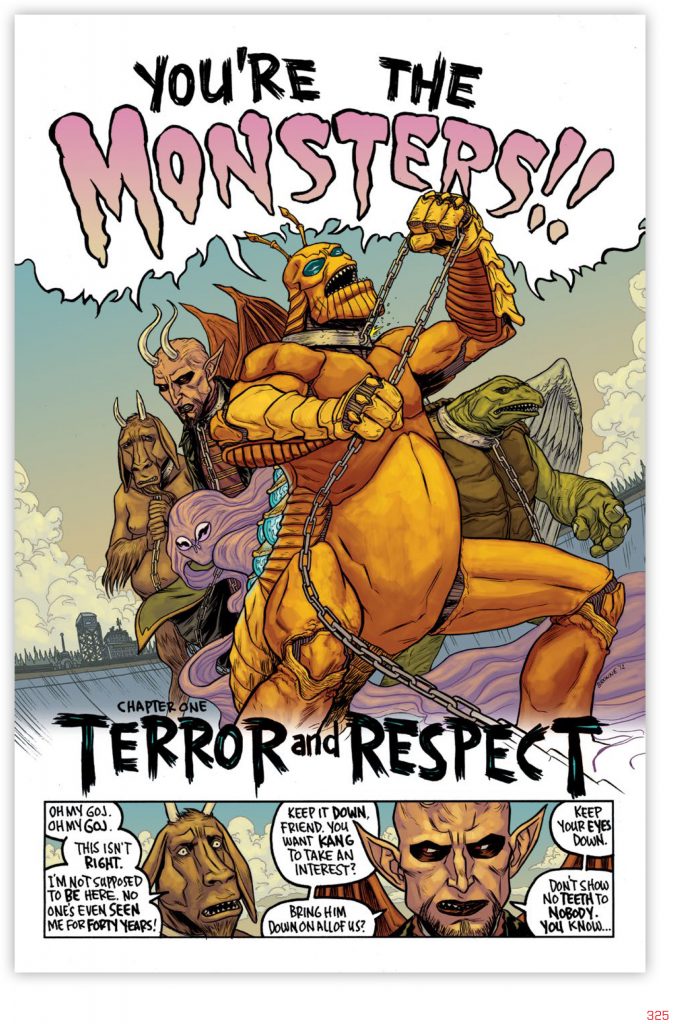

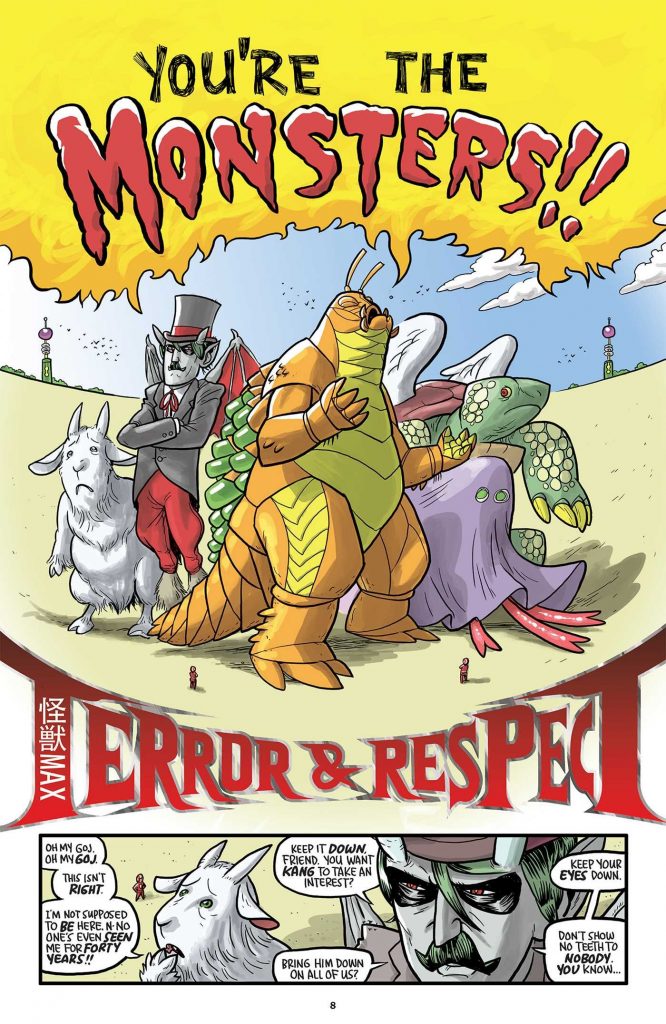

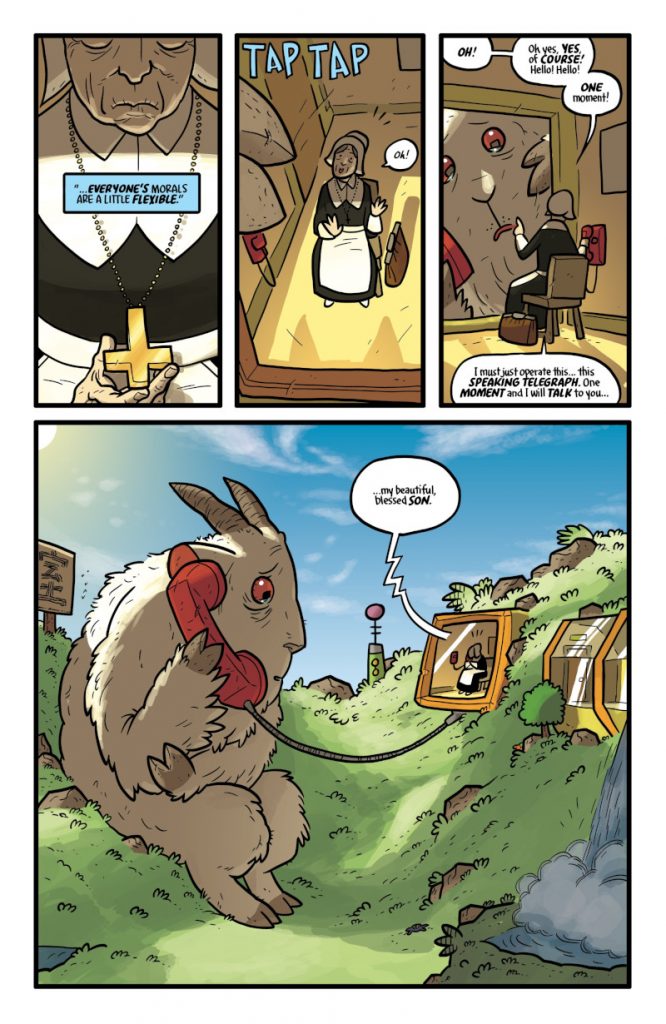

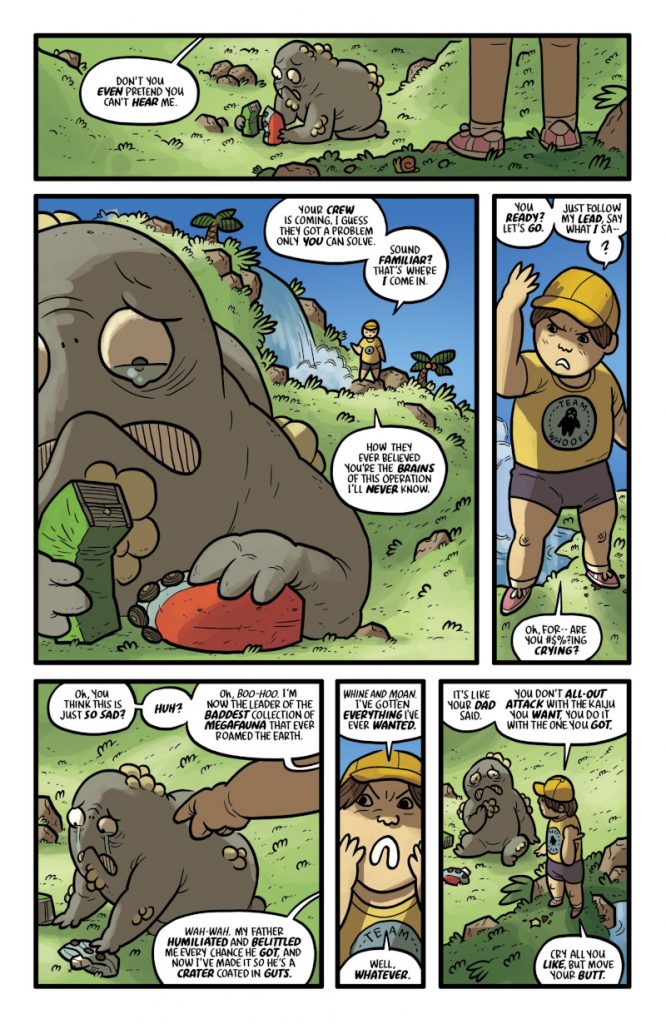

Much of that hopefulness came from the cast itself. The bulk of the ensemble, but particularly a core group of inmates like Whoofy – a fusion of Minya from Son of Godzilla and, eventually, Shin Godzilla – and the Satanic goat creature The Creature from Devil’s Creek (or Daniel), 12 emphasize the complexity of the situations prisoners find themselves in and how not everything is as black and white as it might seem. Sometimes they’re simply trying to escape their upbringing. Other times their experiences may be a lot more complicated than they might seem. 13 If Cannon succeeds at one thing in this series, it’s connecting readers with Kaijumax’s cast, investing us in their lives and well-being.

The level of success he achieved in that regard even surprised Cannon. The cartoonist told me he was shocked by how often people would tell him they really loved or hated characters. 14 Cannon’s been working in comics for decades now, both on for-hire work and in creating his own comics. His usual experience is one of indifference, where people say, “Yeah, it’s pretty good” and move on. He expected Kaijumax and its cast to “sort of blow away in the wind once it was out.” That was not the case.

“Having people suddenly care about something that you do, you would think that that would’ve happened to me already,” Cannon shared. “But it hadn’t really. I was completely surprised by all of that.”

This was important, because Kaijumax’s lead character constantly shifts. While its perceived lead is Electrogor, the aforementioned Godzilla proxy, that isn’t exactly true. I would argue that save for seasons one and two, each season had a different main character – if each had one at all. It’s a true ensemble, with Daniel, a former guard turned inmate named Zhang, a downtrodden, former addict and top kaiju always on the verge of relapse named Dokkeunbi (or Sharkmon), and Whoofy taking the de facto lead spots over the final four seasons, respectively. Everyone gets their moments, even if you don’t always want them to. 15

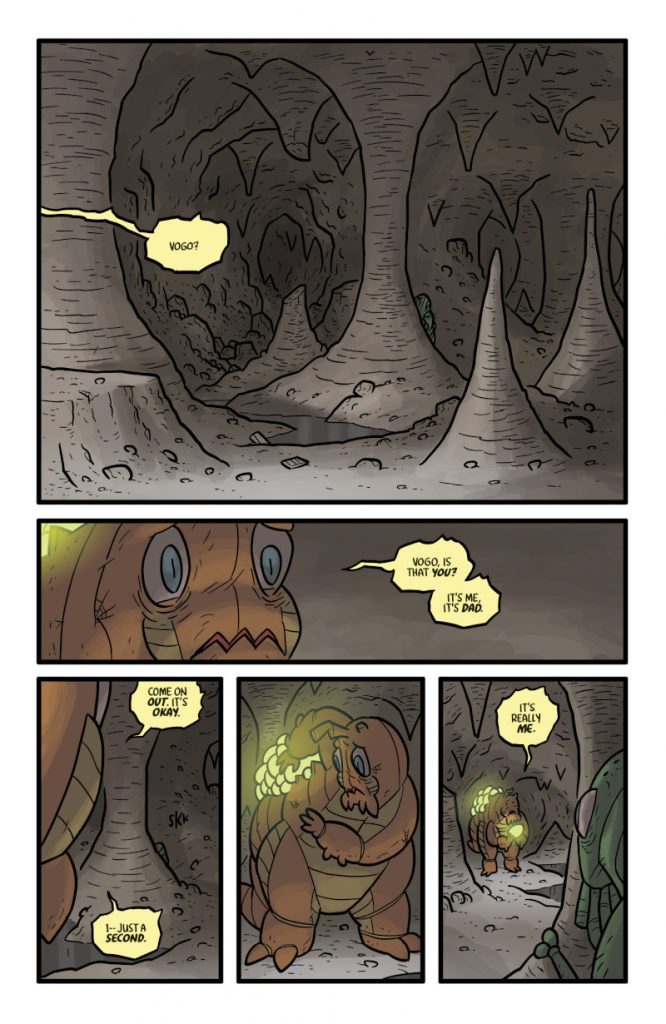

Cannon’s art was another superpower when it came to achieving Kaijumax’s delicate tonal balance. What once almost wasn’t part of the series at all became a defining element of it. His style acted alternately as the sugar that helped some of the darkness go down a bit easier but also as an accentuation to the empathy he created in the story. I even suggested to Cannon that the tears he would draw — with their “Mignola drop” at the end, as he put it, and their impossible to miss nature — were the defining visual of Kaijumax.

You sort of just wanted to climb into the comic and hug the cast, telling them everything was going to be okay, because of how Cannon brought them to life. It was difficult to not feel for these characters when they went through tough times. I’m not a goat whose dad is literally Satan, but I could see myself in Daniel when he struggled. Cannon’s art forged the bonds we as readers had with the cast, while acting as a relatively cheerful counterbalance to how grim the story could get.

“I could push it a little bit grimmer with an art style that looked like Saturday morning cartoons,” Cannon said.

Proving that everything is a double-edged sword, Cannon said his art style was often an obstacle he had to overcome with some readers. Given how particular direct market readers can be about visuals, it created another layer of “not for everybody” to Kaijumax. But readers who bounced really missed out on some incredible growth by Cannon as a cartoonist. Comparing the first season to even seasons three or four shows an artist who developed his abilities immensely in the process of making a whole lot of comic pages. While the storytelling and character acting remains on point throughout, albeit sharpened with additional reps and the passage of time, the cartoonist clearly finds some answers on the coloring side as the series progresses.

The mood and atmosphere Cannon imbues the series with, especially in the later seasons, is astonishing. His colors give his natural, cartoony art style heft and weight to balance the whole endeavor out. Cannon’s ability to bring characters to life and infuse them with emotion is always there. But as his coloring improves, it grounds the story even more. Despite its divisive nature, I’d argue that Cannon’s art was one of Kaijumax’s greatest strengths, and necessary for the entire series to work as well as it did.

Kaijumax culminated in a final season that proved to be one of its best, and a finale that was a stone-cold classic if there ever was one. 16 The overall story of this volume was about an array of the inmates getting involved in a work-release program when a multi-pronged alien invasion strikes Earth, as they’re given the ability to reduce their prison terms in exchange for collecting spaceships and digging trenches around cities, amongst other things.

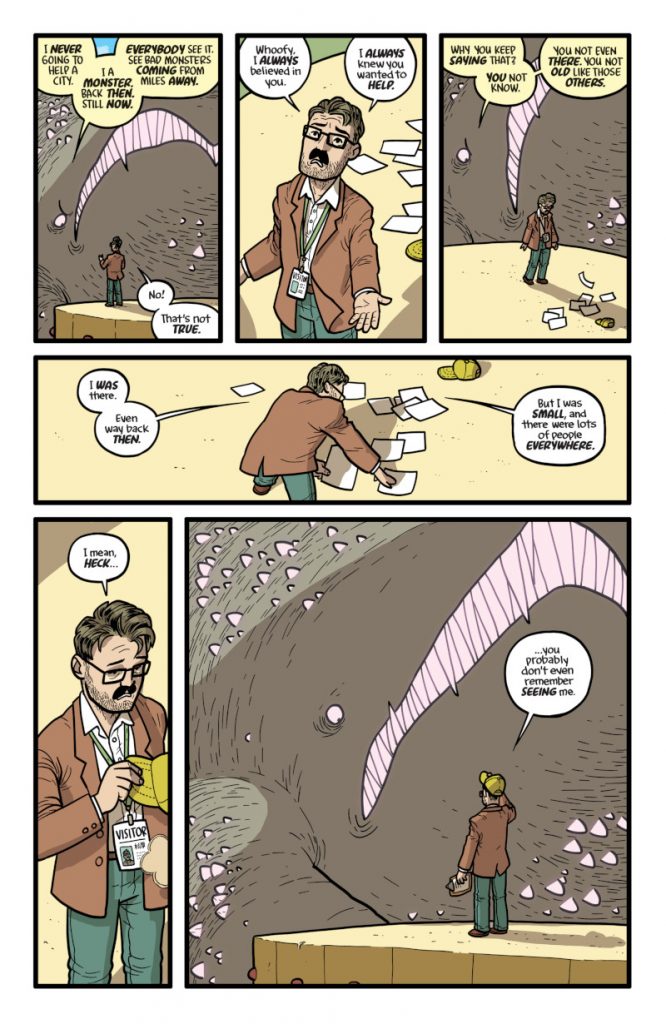

While it is an ensemble season, its big crescendo focuses on Whoofy, a character haunted by a little boy whose death he felt he played a part in when his father rampaged through Chiba, their home city in Japan. That relationship cripples Whoofy, no matter how strong he is, if only because the little boy is a reminder that no matter what he does, he can’t help; he can only hurt.

Originally, the little boy was going to simply be a figment of Whoofy’s imagination, Cannon told me. But like with many ideas in the series, it evolved. Cannon wondered to himself, “what would he be” if this little boy didn’t actually die? That’s where the idea of those affected by kaiju destruction visiting the prison came in: the little boy grew up to be an adult man who helped people find closure after being haunted by those experiences. When faced with the invasion, this character returns, eventually offering the same to Whoofy when the kaiju discovers the man’s true identity, curing the character of something that had long haunted him in the process.

That reveal launches Whoofy into action, as the title’s de facto King of the Monsters nearly single-handedly stops the invasion — with a hand from Warden Kang, who sends Whoofy into space in a callback to a much more harmful beat from the very first issue — and finds absolution as a newly peaceful version of the imaginary little boy is there for Whoofy as he dies at the bottom of the ocean. It’s a beautiful, poignant, heartbreaking moment…and one that almost didn’t play out that way at all! That entire storyline with the real version of the little boy was meant to take place in season five. Cannon just ran out of room! Season six was a pressure cooker because, as Cannon told me, “There was no season to push things to” when it came to the rest of the plot lines he wanted to dive into.

“I had to do the thing that I have never been able to do, which is wrap up all the storylines without cheating and kicking them down the road,” Cannon said.

Like with other substantial changes to the series, it’s impossible to imagine it any other way. Whoofy’s storyline in season six proved to be one of the strongest from the entire series. The sincerity of that character’s final scene even inspired the cartoonist to change the name of the final season. Originally he wanted to called it “Alien versus Prisoner,” an idea he found to be “pretty funny.” 17 Instead, he changed it to “For All Mankind,” a reference to the final conversation between Whoofy and the little boy, saying, “it was too emotional of a season to give it a dorky name like that.”

The rest of the final issue proves to be a tour of goodbyes for our favorites, albeit handled more deftly than that sounds. Cannon even asked certain people who they would like to see in the end, 18 using that list and his own favorites as a guide to everyone he needed to give a sendoff too. As he concluded the final appearance of each cast member, he’d even say out loud, “That’s a series wrap for…” whichever character he was saying goodbye to.

He saved his own favorite for last, as the briefly deceased Ding Wing is resurrected in the final page, reborn not as Giant Monster Terongo, Terror of Pago Pago – as he always asserts is his real name – but as the Protector of Pago Pago. Part of that final beat was in reference to how fleeting the perceived nature of kaiju can be in movies. Sometimes they’re good, like when they accidentally destroy an American aircraft carrier as Ding Wing did, and sometimes they’re bad, with circumstances mostly deciding. Part of it was just giving one of his faves a glow up in the end. For this reader, it also acted as a tacit understanding that things can get better for these characters – even if it’s not always for the best reasons.

There was a lot for Cannon to accomplish in this finale. While his immediate response to completing the series was feeling stunned – “like somebody hit me in the forehead with a baseball bat” – simply because it took a constant part of the last seven years of his life away, there was also fear mixed in. The cartoonist worried, “Did I stick the landing?” I’m moderately biased as an endless supporter, but I’d emphatically argue that he did.

In all ways a creator could succeed, I’d say Zander Cannon found success in the finale of Kaijumax and the six seasons it was a part of. Whether you’re talking about improving his own skills – Cannon told me he learned a lot about each aspect of his work, from writing and drawing to the basic idea of story craft – or discovering what he wants from his comics going forward, Cannon thrived. It’s a banner achievement, in every way a story like this can be.

I’d even describe Kaijumax as a comic book miracle. The history of the medium is dotted with niche, high quality works with no tether to major properties that never find an audience and are forgotten as quickly as they arrive. Cannon thought that might prove to be the case with this series. He originally believed it would be “a gag” that “was going to be probably six issues long – or less.” And sure, it was never a monster hit. But Kaijumax ultimately fulfilled Cannon’s original six season plan, finding enough of an audience to make it all the way.

“It showed me that the type of thing that I wanted to do — dumb ass mashups, absurd over the top storylines, sentimental bull crap — could find a home and a readership that made it financially worthwhile,” Cannon told me.

In the end, Kaijumax wasn’t just the best ongoing series of the past decade. It was living proof of just how remarkable comics truly can be. This series, as depicted by Cannon and Cannon alone, couldn’t have been anything else. It had to be a comic book, and one made by a singular cartoonist. More than that, it started as and evolved into something unlike anything I’d ever read before in the medium, a truly rare feat. Sure, that might have meant Kaijumax wasn’t for everyone. But if that results in it meaning everything to someone, then that’s a tradeoff many storytellers would likely take.

Think Godzilla meets Oz, or perhaps Orange is the New Black if that HBO series from the 1990s doesn’t bring anything to mind.↩

You might be thinking, “Of course someone from Oni would tout a comic they’re publishing.” That might be true, but I know Charlie’s love runs deep. I’ve said before that he’s the only person who loves Kaijumax as much as I do, but I’m sure someone out there has us beat.↩

Shouts to Zonn and Hellmoth. You all sucked until the end.↩

Before you move on, there will be spoilers for the finale in the concluding section this article, so keep that in mind!↩

If you really want to see how deep these references get, Cannon walks readers through most of them in the footnotes of the hardcovers from the series. I love the series and I picked up on approximately 2% of them.↩

i.e. There was a cryptid gang of kaiju, there was a crew of “Legendaries,” etc.↩

You can see more of those in the first Kaijumax hardcover.↩

Who also said “low-key racist things,” as Cannon noted.↩

Think 4chan.↩

This led to a very clear indicator on the cover that it was a mature readers comic.↩

He said early stories were much more influenced by Oz than it was in the end.↩

Or, even better yet, “my son Daniel” as I refer to him.↩

This is not always the case. Sometimes villains can just be bad and do not deserve to be brought back from the brink, as Cannon noted. Shouts again to Zonn and Hellmoth.↩

Celebrating the hatred of characters might seem weird, but passion is passion. Most creators I know simply want readers to feel something. Cannon thrived at that.↩

Cannon shared that the title’s editor, Zack Soto, was invested in a character named Matsumoto not getting a redemption arc, if only because she was often a vile person. Cannon defied his editor and crushed it in the process.↩

Here’s another reminder: if you haven’t read the finale, we’re going to dig in now. Consider this your spoiler warning.↩

I completely agree with his suggestion that it was funny.↩

Including myself.↩