The Creator-Owned Ideal: Looking at the Story Behind Chew as it Begins Its End

I’ve been writing about comics for a long time now. It started with the early days of Multiversity Comics in May of 2009, and if you were actively reading comics or following the industry at the time, you know things were a lot different even then. Uncanny X-Men was on its first – and only – volume after 48 years. Digital comics were in their infancy, as ComiXology was less than two years old and pretty much the only game in town. Direct market revenues were around $25 million that month. In short, comic books were in a staggeringly different place.

One constant since then has been a comic that started the month after I did, and for me, it exists as a bellwether of what was to come for comics. It was an oddity to say the least, and it was something completely ignored by yours truly the week it came out. In fact, it took the former editor-in-chief of Multiversity returning from vacation and being so impassioned by the book’s quality (and the fact we ignored it in our reviews) that he basically forced me to review the title’s first issue.

“How did you not review Chew?” he asked out of frustration.

You have to realize, John Layman and Rob Guillory’s long running Image Comics series arrived in a time where it was easy to slip by. The comics internet was a much more narrowly focused place, and Image was different as well. Now the favored nation of comic publishers, Image at the time only had a 3.78% market share in terms of overall units (they’re normally between 9 and 10% these days), and the arrival of new titles from the “i” wasn’t awaited with as bated of breath. Sure, The Walking Dead was its top book even then, but it was selling two thirds less an issue than it is now. Not only that, but Chew was a comic about a cop that received psychic impressions from what he ate dealing with life after a bird flu that killed millions, and it was by two creators I’d never heard of. It wasn’t the type of comic that generated hype then, at least in part because it sounded weird as hell.

Still, I read the comic, and it was amazing. I was foolish for missing it.

Fast forward seven years and I’m running my own site, Uncanny X-Men is in its fourth volume, ComiXology counts its users in the hundreds of millions, the market is nearly double where it was then, and Chew? It’s won Eisner and Harvey Awards, been a New York Times best seller and has collected editions in eleven languages. While there have been bigger hits, to me, it’s the creator-owned ideal, and a comic that represents the hopes and dreams of what telling your own stories could accomplish better than anything else. And next month, it begins its final arc, leading to its 60th issue – which should arrive by the end of this year – bringing the story to a close.

To celebrate the book’s upcoming beginning of the end, I’ll be looking at the story behind the comic with the help of Layman, Guillory and a couple others, as well as digging into what its overall impact was.

The Story Behind Chew

Even without being aware of him, many comic readers had experienced books that John Layman had worked on well before Chew. Two of my favorite comics ever are Planetary and The Authority, and Layman edited part of the former title from Warren Ellis and John Cassaday and took over the latter when Mark Millar and Frank Quitely arrived.

While he saw success as an editor, his goal was to write, and DC/Wildstorm – the publisher of the aforementioned books he edited – didn’t want editors writing, per Layman. So he struck out into freelance, leading to work on a volume of Gambit and Stephen Colbert’s Tek Jansen amongst other credits. That period for him was up and down for him, bringing both some level of success and lean times his way. He was going through the latter when an opportunity came for him outside of comics, and one that changed the game.

“At the time, my wife worked in journalism, the newspaper was dying, and we just had a kid. Meanwhile, I was recommended for a video game gig from a friend of mine who worked at Nintendo. Activision wanted to hire him and he said it was a conflict of interest but, ‘hey, why don’t you hire my comic book buddy.’ And they were like, ‘oh, comic books are cool, let’s check him out.’” Layman said. “So I wrote a video game job, and it paid something like ten times more than a comic book job did, if not 15 or 20 times. Just crazy money. And one gig after another fell out of the sky.”

“I couldn’t get work for peanuts in comics, but I was getting this crazy video game money.”

One of the games he was offered was a doozy, and it even tied into his true love: comics. A company called Cryptic came to Layman with a big offer. They wanted him to be their in-house studio writer for a massively multi-player online game they were developing for Marvel, with superstar writer Brian Michael Bendis being the idea man behind it. It required a move, but it paid a lot and, Layman thought, it might be a good way to get a foot back in the door at Marvel. So he took the gig.

At the same time, there was this story that was gnawing at him. His cannibal bird flu comedy that he’d been thinking about for a while. Every few years there’s a new apocalypse on the horizon – Zika virus is the fear du jour, for example – and Layman wanted to tap into that in a Saturday Night Live sort of way. But the idea wasn’t fully developed. He had a cannibal cop, the idea the cop would eat things to get psychic impressions, chicken being illegal due to a devastating outbreak of bird flu and a woman whose writing about food allows you to taste it, but that was about it, shared Layman. Then, he had an epiphany: this idea was all about food.

“Suddenly it became a rich universe,” Layman said. “I don’t think I made that conscious connection until after I pitched it to everyone.”

Layman was convinced of the idea, but others around him were less optimistic.

“I’d walk in and William Christensen from Avatar would be like, ‘you aren’t still pitching that idiotic cannibal book.’ Some of my pro buddies were like, ‘this is suicide.’” Layman shared.

Writer B. Clay Moore (Hawaiian Dick, the upcoming Savage at Valiant), was one of the pros he had talked to. He loved the idea, but was skeptical it’d connect with readers.

“When John described the premise of Chew to me, I told him he should absolutely do the book, because there was value in creating an original concept,” Moore said. “I also told him no one would read the book, and that it would never sell.”

Moore shared that Layman knew this as well, which Layman was open about.

“I even did it as suicide. It’s like, well, you know what, you guys are saying it’s not going to sell, and I don’t really care. I’m going to do it,” he said. “It was almost my last gasp of comics.”

You may be wondering why the video game jobs are part of this story. They provided an essential element to Chew getting off the ground: bankroll. After he had gotten the job with Cryptic, a video game check came in for around $15,000 that he didn’t expect. It gave him what he needed to fund Chew, as publishers he had pitched it to had routinely turned it down, including Vertigo Comics multiple times. He had always hoped to have a page rate, but with this surprise income, he was able to go the DIY route.

“Nobody would give me the time of day on this Chew pitch. (I decided) I’m just going to fund it. I’m going to do five issues and be able to say I disappeared from comics for a while, but here’s this kind of cool indie thing I did that hopefully got good reviews and hopefully people liked it,” Layman said. “Chew was supposed to be this thing to get me other work.”

At that point – which Layman estimated to be around April or May of 2007 – he began his search for the last essential element of the comic: an artist. His search didn’t just provide him with an eventual partner; it even lined him up with a publisher in Image.

“At the time, I had a budget and I was going to hire people. So I was calling around to all of my friends saying, ‘hey, I’ve got some money, do you know anyone who would be good for this?’” he said. “I didn’t actually call Eric (Stephenson, Image’s publisher) to pitch. I called him up (because) we knew each other. He took my call and I’m like, ‘hey man, I’ve got this bird flu cannibal cop comedy thing I’m developing. I’ve got a budget and I’m looking for an artist. Do you know anybody?’”

“And he’s like, ‘well, no, but if you find somebody, let me know because I like the concept.’ And suddenly, that changed everything.”

“The most immediate appeal of Chew was just how different it was, to the point that I didn’t quite know what to make of it when John first made his pitch,” shared Stephenson. “There wasn’t anything even close to Chew in the marketplace at that point, and I think that was one of the earliest examples of getting something so unique that it seemed foolish not to at least give it a try.”

“John’s passion for the project was key, too, because he essentially told me that he knew it might not work long-term, but that he had to at least do the first arc to get it out of his system,” he added. “It wasn’t just another job: it was something he had to see through.”

For Image, the appeal was built on how unique it was. Stephenson touted the book as something “as uncompromising as The Walking Dead, without treading similar ground.” At the time – and even now to a degree – the market was filled with comics that felt cut from the same cloth, and Stephenson liked that Chew eschewed any known formulas.

“The best books work because they’re scratching an itch people didn’t even know they had before picking up the first issue, you know?” said Stephenson.

This was obviously huge for the potential for the book, but it also provided Layman with a) an extra perk for potential artists, as the book already had a home, and b) the ability to make Image the bad cop in case they didn’t like the person he eventually chose as the artist.

Meanwhile, Rob Guillory was just starting to make his way in comics. He’d lined up some small jobs after seven years of attending conventions and showcasing his work to anyone and everyone, but he was already entering a potential endgame if things didn’t pan out.

“In July 2008, my wife and I worked out a five-year plan. Basically, I’d quit my well-paying non-comics job to pursue comics full-time, and she would float us with her well-paying sales job. But if at the end of five years I had nothing to show for it, I’d get a ‘real’ job, pursue comics as a side project, and we’d start our family,” Guillory said. “So at the time, I was all in, really. I figured if I was meant to do this comic thing, something would present itself.”

“And literally six days after I quit my job, as I was packing to head out to SDCC, I got my first email from John Layman.”

Layman was connected with Guillory through Brandon Jerwa, a fellow comic writer who was working with the artist on a book at TokyoPop.

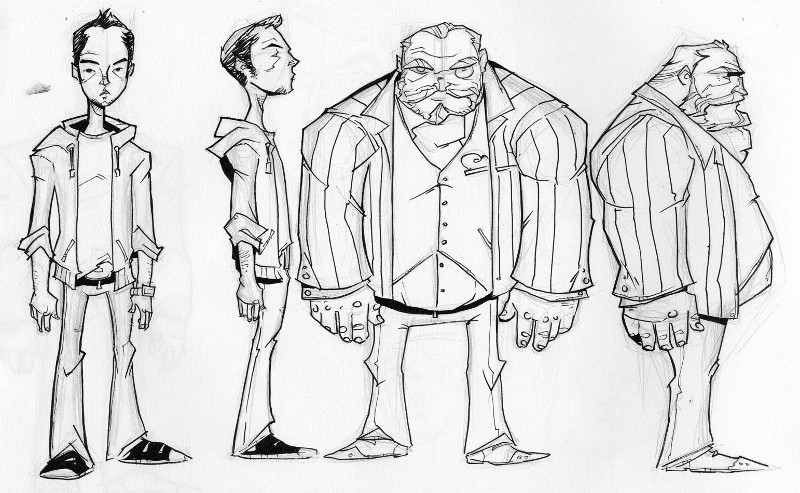

“(Jerwa) told me he had a manga artist, and I was like, ‘oh god, that’s the last thing I want.’ But he’s like, ‘look at his website, he has some kind of cartoony, animated stuff.’” Layman said. “And after that I was like, ‘oh yeah, this is pretty cool.’”

Layman gave Guillory a shot, and almost immediately, disaster struck.

“I had told him I pitched it to Vertigo, and he drew it in this kind of Vertigo style, and then I came back and was like, ‘no, no, no.’” Layman said. “According to (Rob), his whole life he was told, ‘draw it like this, draw it like that.’ So he was trying to ape a Vertigo style. But I wanted kind of a fun book that wouldn’t repel you, and when I describe it, even now, it sounds gross. So I have to couch it with ‘but it’s a comedy.’”

“So I wanted someone you could immediately see and know that this is supposed to be a fun book.”

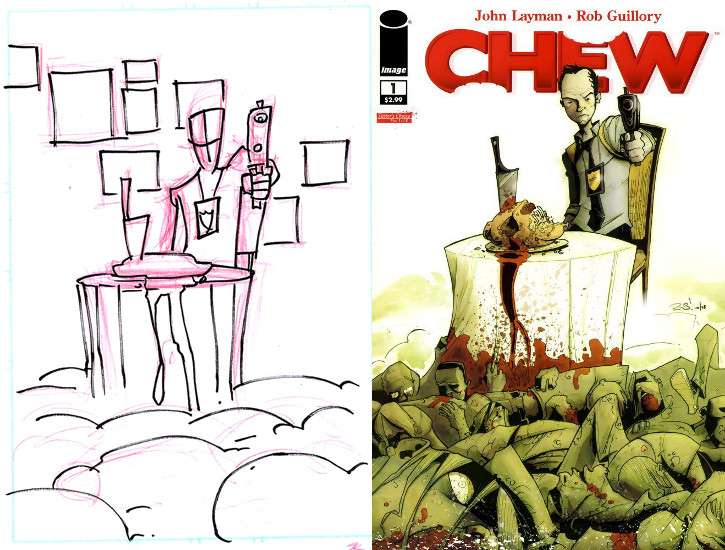

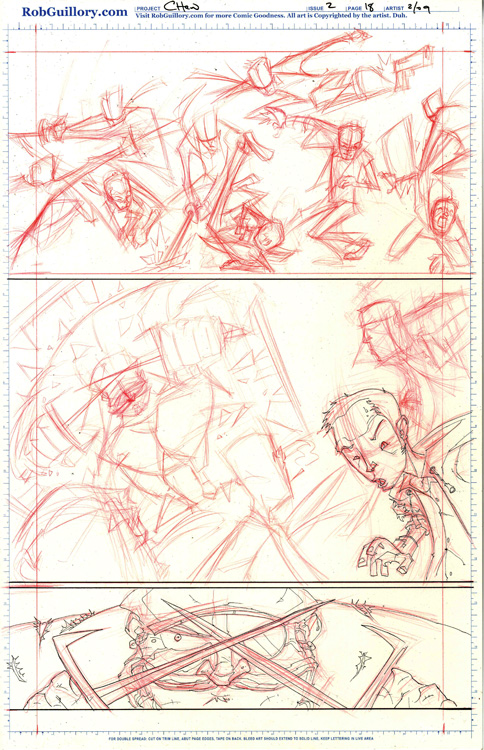

Guillory’s first efforts – which you can actually see in the back of the first Omnivore edition – nearly convinced Layman he wasn’t the right fit. But a conversation led to the duo unlocking what was needed to make it work.

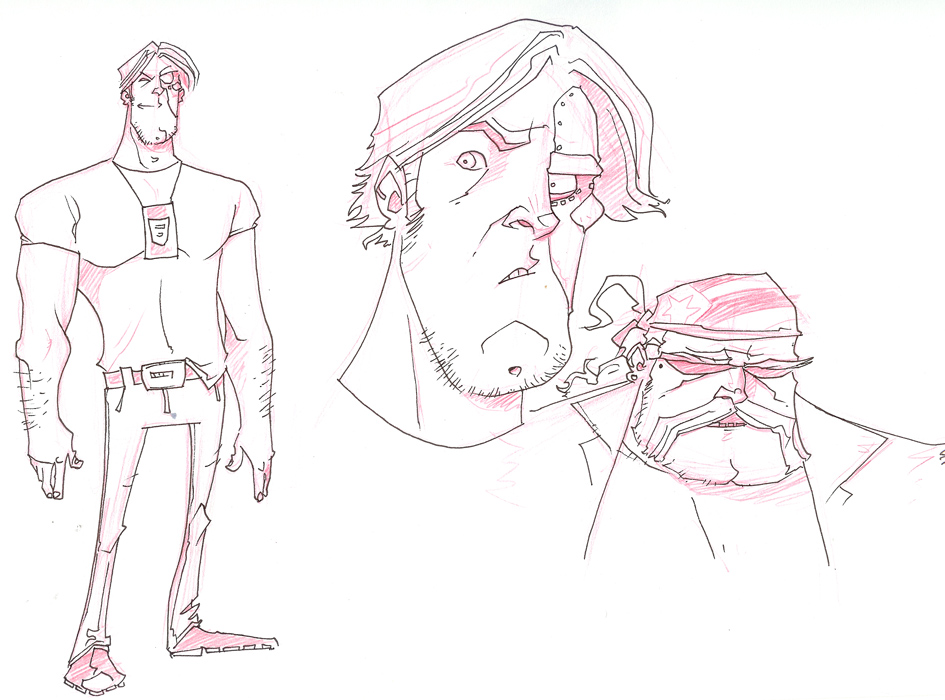

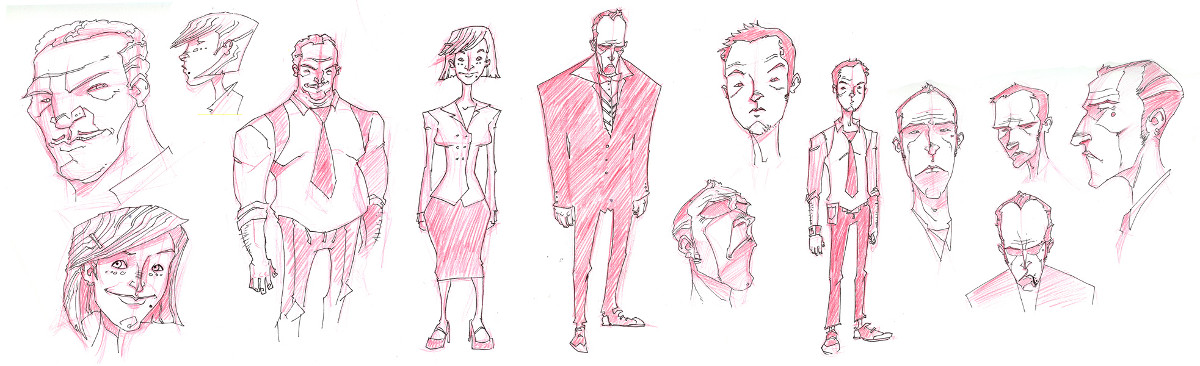

“Honestly, I didn’t ‘get’ Chew at first. I didn’t get the tone he was going for,” Guillory said. “Ironically, the tone he was wanting was exactly what I specialize in, but at the time I had a hard time believing someone wanted to pay me to basically goof around on the page – which is what I do.”

“I had a very specific paradigm for what comics could be, and I’d never really been exposed to a genre-bending book quite like Chew. Don’t get me wrong, Chew is absolutely my kind of comic, but up to that point, not many people wanted to hire me because they weren’t sure a book with my goofy art sensibilities would sell,” he added. “In the end, Layman just told me ‘do what you do,’ and I did, not thinking other people would actually buy it.”

“Fortunately, I was wrong.”

“Rob was important, I think, because he has such a distinctive style,” Stephenson said. “There needed to be something a little quirky about the artwork for Chew to work, I think, and that’s a big part of Rob’s charm. He has his own approach — there’s no mistaking his work for someone else — and I think that helped make the world of Chew its own thing.”

One of the most interesting things about Chew’s beginnings is how both Layman and Guillory were in rare positions to make an outlandish book like this succeed. I said it earlier and I’ll say it again – Chew is a weird as hell book – but for it to work, it needed a pair of creators who would be willing to commit to the idea in a way most would be fearful of. Whether it’s a conscious decision or not is uncertain, many people who create stories in a variety of mediums chase ideas that have a higher potential for success over what they themselves are connected to. Layman even shared many suggested he just make a superhero comic simply because that’s what the market wanted then. But because of Guillory’s five-year plan, Layman’s video game money, Image’s hands off nature, and the fit of the three together, they were able to just do what they wanted to do and see where the chips fell at the end.

“I’d never taken on anything like it, but I had nothing to lose,” Guillory said. “I saw the opportunity, and I was determined to make it work.”

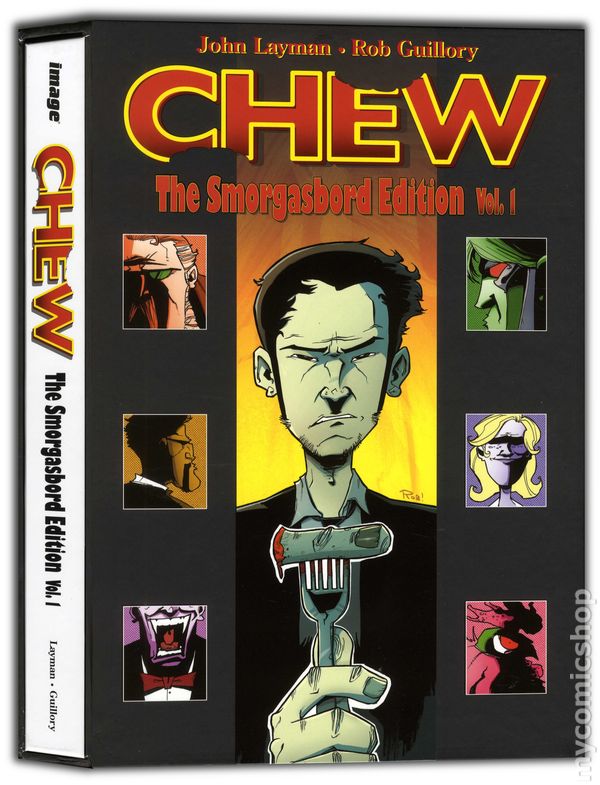

And work it did. From the start, the book connected with readers and retailers. Even Layman described it as “this kind of freak hit,” and as noted earlier on, the book’s seen a level of success few titles can really match. Its first year, it won the Best New Series Award at the Eisners and Harveys while Guillory was named Best New Talent at the Harvey Awards. The next year, it won Best Continuing Series at the Eisner Awards, and it has sold innumerable copies of its bevy of releases. When it’s all said and done, the book will have released 60 issues (not counting four different specials they’ve done), 12 trade paperbacks, six hardcovers and three gigantic compendiums they call “smorgasbord” editions. It’s currently in eleven languages, and in France, Germany, Italy and Spain, there are already ten editions out. It’s big in France in particular – Guillory once shared he thinks it’s because of their love of food – and there, it has an even better title: Tony Chu, Detective Cannibal.

I asked both creators about the success of the book, and that’s something they take a lot of pride in.

“There have been a couple moments where I’ve stepped back and thought. ‘Is this real?’” Guillory shared. “In a lot of ways, I still feel young in comic industry years, though I’ve got almost eight years of Chew under my belt. But for the most part, I don’t have the time to stop and soak in it too much.”

“When I wrap the last issue in October, one of my goals is to read the whole series. It should be a fairly emotional thing, I expect.”

“It doesn’t do the gangbusters that it did, but now there is more of it, so it’s like death by a thousand paper cuts, but the paper is money,” Layman said. “So we’re still making good money even though we’re not as hot, and frankly, I like it better now that the heat is off us and we’re not the darling. “

They’re hoping the book could find even more success later on – Layman noted that there’s a whole new audience out there of readers who wait until the end of a story to binge read it – but as mentioned before, it’s incredible for many reasons they’ve reached the heights they have. Beyond the fact that it’s such a strange book – Layman admitted, “no one quite understood it or knew what to make of it, including myself” – they had a unique wrinkle to deal with for a book that’s going to ultimately run 60 issues: its artist had never even drawn one complete issue to that point.

“Figuring out how to do pencils, inks and colors on a monthly-ish book was by far the hardest part,” Guillory said. “Before Chew #1, I’d never finished a complete issue of a thing. It was always a four-pager in an anthology here, or an eight-pager there. I’d never carried a book visually before, so that was tricky.”

“Early on, I just learned to make it as good as I could, then let it ride. I think every artist learns to strike that balance between ‘this art isn’t perfect’ and ‘yeah, but I can live with it because the deadline.’” he added. “So that was tricky. I doubt I could have kept my sanity without the great color assistants I’ve had over the years – Taylor Wells, Steven Struble and Lisa Gonzales.”

After about three issues, though, Guillory found a comfort level that allowed him to embrace his own art and cut loose in a way that fit him best. And after working together for so long, their process is as well oiled as any in comics.

“After 60 issues, we’ve developed a serious shorthand. I generally know what he’s going for, and he knows what I’m bringing to the table. If there’s something special he wants me to try out, or some new trick I want to play with, it only takes a phone call to get on the same page,” Guillory said. “It’s a great dynamic.”

Layman shared that early on, he was meticulous about each and every detail of the book. He’s not just writing the book, but lettering and providing production work on it as well. Early on he’d “agonize over errors,” but now it’s old hat to him. He admitted it’s easy enough for him these days that one of the issues was pasted up when he was drunk after a day at a comic convention in India.

“So many times because I’ve done a lot of international travel, I’ll end up in my hotel in the wee hours of the night putting a book together. It’s really gotten second hand,” Layman said.

And after seven years, that’s helped them maintain a position as not just a great comic, but also a consistently released one. While they’ve had slowdowns in their release schedule from time to time, it’s always for personal and inescapable concerns (example: Guillory’s about to have his third child over Chew’s lifespan). When the whole thing comes to a close, the book will be seven and a half years old and they’ll have released 64 issues when you include the specials. It’s an incredible level of consistency that has helped with their success – after all, few things are a greater kiss of death in comics than delays.

They garner less attention these days, but that’s because their book is now a graybeard of the comic industry. Check a sales chart: Chew is one of the highest numbered titles out there. That’s okay with the pair, as the title continues to thrive despite limited press and their awards pipeline drying up. That doesn’t mean their influence isn’t still felt, though, especially as the book comes closer to its conclusion.

The Legacy of Chew

I’ve held a theory over much of the lifetime of my writing career, and it’s probably not a widely held one. It’s that Layman and Guillory’s Chew is quietly one of the most influential comics of the past ten years.

You may scoff at that idea, and that’s fine. But the month Chew debuted, the top selling Image titles were two Robert Kirkman books, Spawn, a Witchblade title, something created by actor Milo Ventimiglia and a crossover I’ve never even heard of featuring some Top Cow superteams, the Mighty Avengers and the Thunderbolts. It wasn’t just Image that was different; everything in comics was different. Then, this totally ridiculous comic about a cannibal cop dealing with a chicken fearing world arrived, and it was a success. It didn’t light the world on fire – it has never been a top 100 seller, let alone a top 10 one – but it was and is a profitable endeavor, something that generated accolades and awards, and above all, a great comic even after seven years. Not only that, it came from two lesser-known creators.

To manipulate an Anton Ego line from Ratatouille, “not every comic can become a big success, but a successful comic can be anything.” Chew was proof of that. It showed everyone in the industry that comics don’t have to be one thing to succeed: they can be whatever you imagine, if done well. While it wasn’t responsible for the creation of the creator-owned giants of today, it’s easy to look at Chew as proof of concept that you don’t need a gigantic TV deal to find success as someone who makes comics for themselves.

I asked Stephenson about Chew’s influence, and he had similar thoughts.

“There’s no way I could have asked John to pitch a book like Chew. It had to come from him, and from Rob, and that’s the beauty of the best creator-owned work. John and Rob have been incredibly successful doing exactly what they want to do, telling their story exactly they way they want to tell it, and at their own pace,” Stephenson said. “In a lot of ways, I think Chew was the book that showed other writers and artists they could do literally whatever they wanted and have a shot at success.”

While Layman was hesitant to echo my sentiment, Guillory shared he’s heard people talk about this idea before. He thinks they were “at the right place when the stars aligned” when it comes to Image taking off, but he did agree with one point I made.

“If Chew can take credit for anything, I think its success probably inspired other creators and publishers to try their wildest ideas,” Guillory said. “The lesson is: if Chew can succeed, anything’s possible.”

The biggest difference Chew has made, though, has been in the lives of its creators. While both admit they’d like to think they’d still be in comics to some capacity without Chew, it’s hard for either of them to imagine what their lives would be like without it. Layman shared he’d probably have a non-comics job, but he’d probably still be trying to make comics work and worrying about every detail of emails from editors.

“It is fair to say that Chew has completely changed my life at this point,” Layman said. “I’ve seen the world and now I have a degree of financial security, and granted, my wife still has a job – she’s actually phased into a great one – but the idea that I’m going to take three months off (after Chew) and creatively recharge…not a lot of people can do that.”

“I’m cognizant of how crazy lucky I am.”

Layman’s diligently working on the final scripts, even though he’s known how the series was going to end from the very beginning. He’s excited to take a break from comics, but there’s plenty of work to do – characters to kill, threads to tie up, and a fittingly “Sopranos-esque ending” to deliver.

While writers have the bandwidth to tackle multiple projects, Guillory’s been in a mostly exclusive marriage with Chew for the past eight years. Because of that, he’s going to miss his collaborator above all.

“I’ll miss the back and forth with Layman the most. Of course, we’ll still be friends after this, and I still plan to bug him from time to time, but there’s nothing quite like a creative collaborator,” Guillory said. “It’s like he and I have been in the middle of this ongoing conversation that’s lasted eight years. That’s insane. So I’ll miss that, until our next work together.”

“And of course, I’ll miss the characters, but I have the feeling that I’ll be drawing Poyo until my dying day.”

The biggest thing for Guillory, though, is just how much Chew has changed his life, partially because of how his personal life has paralleled what’s been going on with him professionally.

“When I began Chew, I was 26. My wife and I had only been married a bit over a year. And career-wise, I was a newbie to the industry,” he said. “Eight years later, I’m 34, and we’ve been married for almost a decade. We’ve had all three of our kids over the course of Chew’s run. And even more personally, I became a Christian over the course of Chew, and I have more peace and joy in my life than I’ve ever had.”

“And of course, career-wise, Chew has opened up opportunities at just about every major comic publisher, so I feel like I’ve got an open field before me. I really can’t express how game changing this book has been for me,” he added. “It’s enabled me to provide a life for my family that I could not have fathomed, and it’s taken me places I hadn’t dreamed of going. It’s opened doors, professionally and personally.”

“In a lot of ways, Chew set the table for whatever comes next. And I guess when you come down to it; it’s just fitting to end on a food pun, right?”

Chew begins its end next month with issue #56, and whatever happens in the remaining five issues, its impact will continue to be felt by the readers that enjoyed it, the creators it inspired, the publisher it worked with, and most of all, the two men it changed everything for.

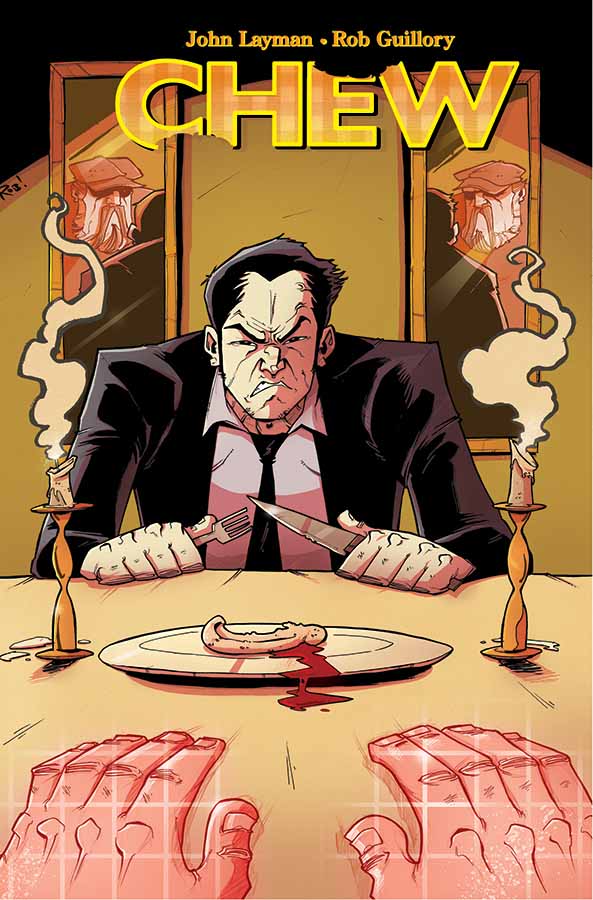

Header art from the cover to Chew #15, with art by Rob Guillory. Haven’t read Chew yet? Visit the book’s page on the Image site to get caught up in print or digital.