Comics as Memes: An Exploration of the Potent Memeability of Comics

If there was some sort of way to magically track the most widely viewed comic moments from the past decade, the list would almost certainly be comprised of a motley crew of titles, and one that would at least initially confound the average comic fan. You’d browse the list and meet it with a quizzical face, as beats from Batman or Saga or My Hero Academia or Raina Telgemeier are absent. 1 Instead, you discover random Marvel comics like 2008’s The Incredible Hercules #122 and 2015’s Spider-Man and the X-Men #2, a relatively ancient DC title like World’s Finest #153, or webcomics like “On Fire” and Nancy comprising the bulk of it.

“What’s up with that?” your brain might wonder.

“Why are those so well known?”

The answer is simple: each of them contains a panel – or panels – that became a notable meme. Respectively, they were:

- Fred Van Lente, Greg Pak and Clayton Henry’s Incredible Hercules #122 was home to the “Cool story, bro” thumbs up

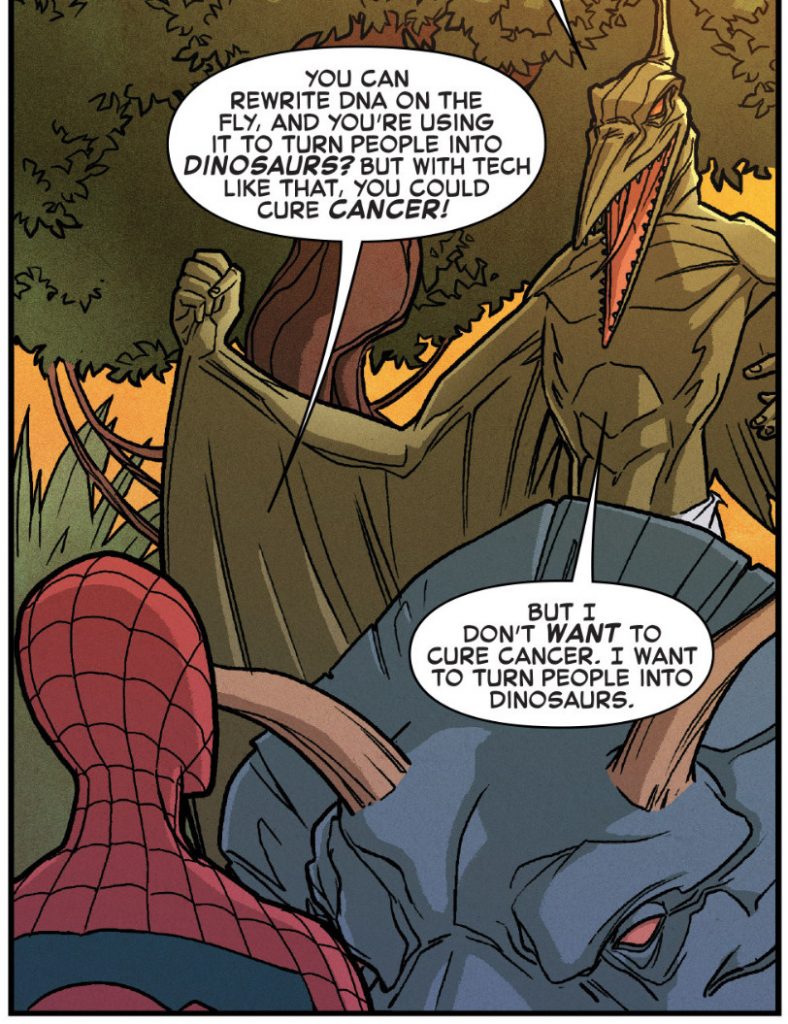

- Elliott Kalan and Marco Failla’s Spider-Man and the X-Men #2 houses the beat where Sauron tells Spider-Man he doesn’t want to cure cancer, he wants to make dinosaurs

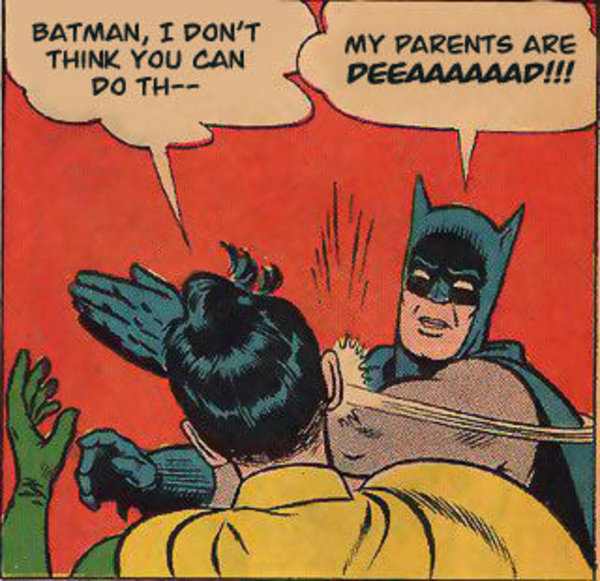

- Edmond Hamilton and Curt Swan’s World’s Finest #153 is where the “My parents are deaaad!” meme originated from

- Olivia Jaimes’ Nancy strips gave rise to the glory of “Sluggo is lit”

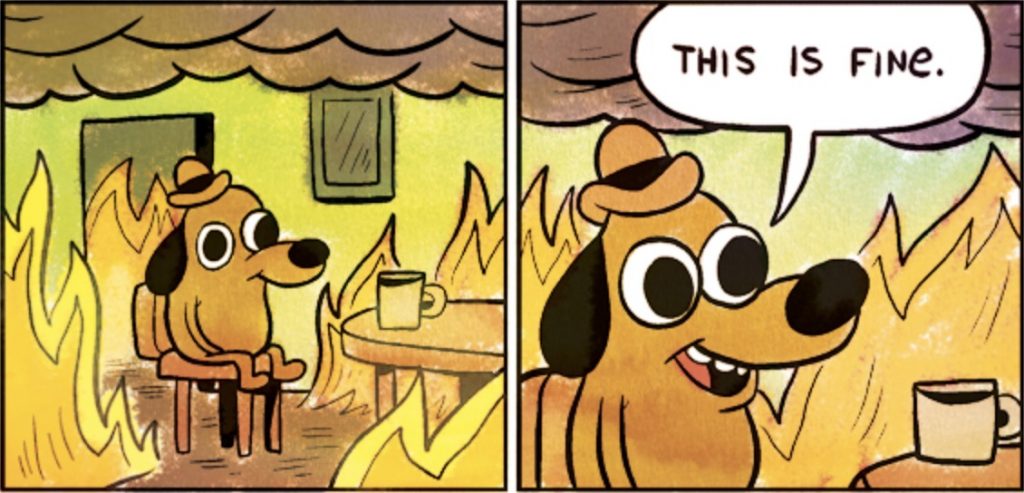

- Lastly is arguably the most famous comic meme of them all, as KC Green’s “On Fire” is where the “This is Fine” dog came from

While the average reader of this article likely has read, at most, one or two of these original comics, I’d wager every single one of you has seen the memes they spawned many, many times over. They’ve become inescapable at times, popping up when you least expect them. And that stems from the fact that memes are, for better or worse, one of the dominant forms of communication today. But what are they exactly? Blake Bowyer, the Digital Director of Integrated Accounts at Nike 2 shared that while the term originates from Richard Dawkins’ 1976 book The Selfish Gene – in which the term was defined as a “unit of culture,” which is still a strong fit today – he believes “the best way to think about memes is as a form of communication or a vehicle for a message – from everything to a joke to a political position.”

The standard meme format is a combination or juxtaposition of words and pictures. And what is a comic if not a form of communication comprised of words and pictures as well? Of course, that’s where it’s important to note something: not all memes are comics in a traditional sense, nor are all comics memes. While there is a ton of overlap, it’s a bit more nuanced than any one-for-one connection. As KC Green himself told me, “I think the language is definitely blurry for people outside of the comics circle. I don’t think they’re completely wrong, but it’s not 100% right either.” But there is undeniably a connection there, and the obvious parallels between the two – both methods of communication in a way, both built off words and pictures – make comics arguably one of the greatest sources to fulfill the internet’s undying thirst for memes.

“They’re short, making them easy to digest while just scrolling – people will be more likely to share (a comic) than a meme with a wall of text on it,” Kyle Stratis of Danqex – a meme valuation and trading platform – told me of the meme power of comics. “They also are easy to edit, allowing people to subvert the original comic or allow it to mutate without altering the art, which may give the now-template comic new life.

“It seems convoluted, but comics are actually uniquely positioned as a shareable piece of content because of their structure and editability.”

Stratis makes an interesting point with the editability of the comic form. While some creators would (understandably) bristle about that, the malleability of comics is an important part of their relative meme friendliness. That happened with the aforementioned World’s Finest #153. You likely are familiar with the meme version of the above panel, but that’s not what the characters actually originally said. Its initial form was relatively milquetoast and odd, but once the internet got its mitts on it, this panel became something transcendent in its life as an oft modified meme structure. While the “My Parents are Deaaaaad!!!” flavor is the most well known variety, it’s regularly altered, shifting its meaning and impact each time. And while Stratis was speaking to the text of comics in particular, it can be the images instead at times, as Dan Walsh’s momentous and haunting comic strip variant Garfield Minus Garfield proved.

Elliott Kalan, who wrote the aforementioned Spider-Man and the X-Men #2, believes another reason comics make excellent memes is “there’s something really portable about individual panels.”

“They mean something specific in the progression of the story, but the right panel isolated from the larger story can have all kinds of other meanings and metaphors projected onto it,” Kalan said. “In an image-based culture like ours has become, where people respond to the emotional punch of an image much better than they respond to a block of text, a comic book panel is essentially a readymade meme that can be drafted into service to get across what feeling or idea you want to communicate.”

“And the irony inherent in knowing that it was created for a different purpose than you’re using it for adds a layer of humor that makes the whole thing more charming and attractive,” Kalan added. “So in this way, Sauron being selfishly honest about his goals becomes shorthand for any powerful person throwing resources at a dubious hobby instead of helping other people — and the humor of comparing a real person and a pterodactyl-man makes it go down easier than just saying, ‘Elon Musk is being selfish,’ or whatever.

“It’s like someone took Roy Lichtenstein’s method — to take someone else’s comic book work and separate it from its original context — and actually found a real use for it besides just making Roy Lichtenstein money.”

Green believes it’s because “comics can capture a vague feeling in most people’s heart who may not have the real understanding of what or why it’s there,” saying the medium acts as a universal language even for those who don’t traditionally read them. That’s a big part of the reason he believes “On Fire” connected with people as well as it did, as he described the strip as purposefully “vague.”

“It was a way to capture the feeling of continuing on even in the face of overwhelming dread for life, yours or otherwise,” Green shared. “That’s something I always like to boil down and capture to its essence and, well, I guess I found it.”

The interesting thing about this now ubiquitous beat – “This is Fine” might be one of the most lasting and eternally useful memes we have – is that in the moment of its creation, it didn’t feel like anything altogether special to its creator. There was no magical, aha moment upon finishing it. In fact, Green described it as “business as usual!”

“It was just ‘Wednesday’s comic’ in my mind. It seemed almost overly simple to me, which is why I did the ‘fancy’ or ‘different’ coloring job on it, making it look all pixel-y looking,” Green said. “I remember a friend saying it was their favorite at the time, but I didn’t really see it (being) used more and more ‘til about a year after it came out.”

That’s fairly standard for the moment of meme creation in comic form. When I asked Fred Van Lente, the co-writer of Incredible Hercules #122, about the famous “cool story, bro” moment, he first explained everything that went into it, because the moment very much is spawned from the plot of the story. The comic was a funny one, but this moment becoming its own thing was, at least initially, more a product of true comics collaboration than any deliberate focus on elevating the famed thumbs up itself.

“Greg (Pak, his co-writer) actually wrote this bit, but–and I remember this distinctly–he made it the last panel on the page,” Van Lente told me. “My big contribution is I saw the potential here so I bumped it to the top of the next page, so you got it as a surprise on the page turn. And Clayton (Henry, the line artist of the issue), who is really one of the best at acting of anyone I’ve ever worked with in comics, obviously saw exactly what we were going for and totally nailed it.

“This definitely was a team effort, though the initial idea was absolutely Greg’s.”

It took the team to nail the moment, although again, it was still a part of a larger whole. And at the time, it wasn’t that big of a deal. It was part of a well-liked run, not a standalone segment, short of the occasional review touting it, more than likely. It took time for that moment to become a classic meme. But when it hit, it hit hard.

“It wasn’t until I saw the meme crop up in forum postings that I realized that the panel was something people were re-appropriating and it had this life of its own,” Van Lente said. “I’d be surprised if even a tenth of the people using the meme know its origins.”

That’s the fascinating and tricky part of comics as memes, of course. These isolated moments often do very little for the comics and creators themselves. Take Kalan, for example. That Sauron moment has been shared thousands upon thousands of times, with views of that panel almost certainly totaling in the millions. But Kalan – despite his position as the current head writer of Mystery Science Theater 3000 and former role as the head writer for The Daily Show with Jon Stewart – described himself as “a pretty minor comics writer,” saying that moment from Spider-Man and the X-Men #2 “is 99% of what people talk about if they’re talking about my work at all.” The connection between comics and memes is real, but it’s often one way in terms of which medium gains from it.

But that isn’t a universal truth. Creators can benefit from the fame of their comics turned memes. Green told me “This is Fine” “absolutely” made a difference in his life, as his monetization of that idea gave him previously unimaginable amounts of creative freedom.

“It’s made it so I can continue to float on and be a weird creator with a comic called ‘Fuck-Off™’ now or continue with my esoteric Pinocchio retelling,” Green said. “I always had ups and downs when it comes to where the money comes from next, always a yearly ‘big project’ that will likely empty me out come tax time, but ‘This is Fine’ and the Kickstarter for the plush have helped me (be) able to not worry so much and figure (out) where I want to go next.

“Being free enough to try something different is something I have ‘This is Fine’ to thank for.”

Of course, with great power comes great responsibility. And unfortunately for comic creators turned unexpected meme creators looking to actually own what they did in a way that benefits them, that means dealing with a whole lot of knockoff merchandise. That’s something Green describes as “more of an annoyance than something that’s really hindering (him) in any way,” and it has ended up working to his advantage. Off-brand merch has become the de facto research and design unit for his own store. He said one of the best ways of “combating bootleg merch is to make” his own version of it. Negatives become positives, annoyances become advantages. You gotta love it.

It’s not just these comics that have succeeded thanks to the meme-friendly nature of comics, of course. While some of these fit into some rather nebulous gray areas of “are they really a meme?” because they’re really just comics, efforts like Hannah Blumenreich’s Spidey-Zine, Lucy Knisley’s Linney strips, and Kate Beaton’s slice of life comics on Twitter fit the mold of this whole idea in their own way. While they aren’t technically memes, shortform comics that are social media friendly fit within the same ultra-shareable space memes do, capitalizing on the same mechanics in perhaps a different way. And when they work, and work well, they can earn you gigs, publishing deals, and legions of fans. That’s impactful. It might be apples and oranges, but we’re in the same ballpark, if you don’t mind me mixing idioms.

All of this makes me wonder whether or not there is something untapped and worth digging into when it comes to the connective tissue comics and memes share. After all, meme marketing is very much a thing, and has been for quite some time. 3 As Bowyer told me, “Thinking about memes as a form of communication, any medium like memes can be effective as marketing if done properly.”

“Memes are a unique language of the internet, which is broken into communities – from large (e.g., Facebook) to niche (e.g., a sneakers subreddit). Brands can use memes as a way to relate and speak to those communities in relevant ways,” Bowyer added. “This is done at varying levels of success and can, of course, lead to brands overengineering or trying too hard.”

Meme marketing is something that is regularly happens each and every day, whether you’re talking about a brand participating in some unholy creation like the broom challenge or desperately trying to stay hip with memes they don’t quite understand. That can be a double-edged sword, of course. Failure at playing that game is a one way ticket to being ridiculed on the “How Do You Do, Fellow Kids?” subreddit, 4 as Stratis noted to me.

But each double-edged sword comes with a good side, as well. There can be value there, as a comic or really anything becoming a meme can benefit its source material, if you play your cards right. Bowyer cited Baby Yoda and Old Town Road’s memeability playing a part in the success of The Mandalorian and Lil Nas X, with other easy examples including Bird Box and Untitled Goose Game. They can aid in discoverability and drive engagement. Stratis personally vouched for the idea, as he said memes exposed him “to comics, entertainers, etc. that (he) otherwise wouldn’t have heard of.” Because of that, creations being converted into memes can be hugely impactful for creators. Just look at Green, whose life changed because “On Fire” morphed into what many know as the “This is Fine” meme. Being meme friendly can lead to gains for comic creators.

But can that help comics? That’s the tricky part. Green’s financial success with “This is Fine” largely came from selling merchandise, not comics. And crucially, his comic was free to begin with. I tend to believe that webcomics are the most likely to benefit from meme marketing, if only because they’re free to access, making them inherently easier to discover and share. As Stratis said, they’re “basically created for sharing,” which then “democratizes that creation,” enhancing the discoverability of the comic in the process. Print comics are naturally more difficult to share, they cost money, and memes are often less predictive of the content that will surround a notable panel like famed Marvel moments like “cool story, bro” or the Sauron beat. There’s more of a distance there. 5

But this is where the importance really reveals itself: while it’s true much of Green’s gains were because of merchandise, it did fund his current and future comic work. And that’s an essential consideration. Comic-related gains are still gains for the creator, if they own it. If it’s something you own as a creator, you can tap into the heat your comic accidentally (or intentionally) created. That’s important.

The other complicated part of tapping into a larger market for your work by blending your comic into meme culture is the trickiness of intentionally making memes. While Bowyer described memes as “mostly intentional” – which I largely agree with in typical circumstances – comics can make strange bedfellows with memes in one specific way. Comics are mostly designed as narratives or reflections of something you’re trying to convey as a storyteller. By trying to force a meme-like experience into your work, you might fail at your primary objective. There’s a tension there, and its why a lot of the co-mingling between the two can feel cheap or forced. Just look through Instagram at cat meme comics, sometime. They try so hard to be a meme their success as comics often crumbles. Beyond that, it’s inherently unpredictable, as Green shared.

“Intentionally trying to make a ‘meme’ would almost always fail in my eyes, (because) you can’t control what people glom onto online,” Green said. “You can’t guess what’s gonna go viral or what people would give a shit about. Leaning into it just seems disingenuous to me, and I bet most people can feel that too.”

That’s not to say there isn’t opportunity at the intersection of comics and memes. Obviously there’s monetary value that can come from it, or perhaps even more importantly to some, real opportunities for discoverability. But one other marvelous, underappreciated value of this idea is – if you assume that, roughly speaking, there’s a significant overlap between how memes and comics work – that the ubiquitous nature of memes means huge swaths of people already understand the language of comics without necessarily reading them.

I’ve had several people say to me, “How do you even read comics?” and that’s a perfectly legitimate question. For some, the medium doesn’t even make sense as a storytelling form. That’s a massive roadblock, and probably – hopefully! – part of the reason Marvel is releasing a comic that is literally called “How to Read Comics the Marvel Way.” 6 More people might read comics if they understood them, and memes are almost a Rosetta Stone for the comic medium, a familiar form that translates the language for many to see. That’s where I think there is enormous potential value, even if I don’t totally know how to connect those ideas.

Regardless of value, the marriage of memes and comics is a fascinating, fruitful combination, and one that beautifully highlights the medium and form. Is it an idyllic, comics romantic-friendly fusion? Probably not, as purists might argue the former devalues or even invalidates the latter. But it’s an unstoppable pairing, with comics forming an eternally sustainable supply of material for lovers of memes. It’s going to be a connection for a long, long time, whether we want it to be or not. And while it normally works where memes gain from comics, perhaps that connective tissue could work the other way as well, helping comics find a larger audience and creators monetize their work. That would be a very fine thing indeed.

Okay, you might find a few of those too.↩

Also the former Group Director (EVP) of Digital Marketing Strategy & Planning at Golin, a Chicago based PR Agency.↩

The earliest mention I could find was in a 2009 AdAge article.↩

Which itself is named after a meme derived from 30 Rock that is largely used to make fun of brands and older generations awkwardly trying to fit in.↩

Interesting tidbit: print comics like World’s Finest #153 have seen upticks in secondary market interest because of the notable memes they contain.↩

Written by master of the meme arts Christopher Hastings, no less.↩