Does Marvel have an Event Problem?

Every comics publisher reacted to the coronavirus pandemic in slightly different ways, both from a content standpoint and when it comes to retailer incentives. It’s a crazy time, so for many publishers – most notably DC, but also houses like BOOM!, Vault and beyond – it’s the perfect opportunity to try out new approaches and aggressive strategies in hopes of helping shops and/or sculpting a better position within the market for themselves. Responses naturally have varied, but they’re trying to find solutions to these new problems in a time that’s desperate for them. That’s commendable.

Like those publishers, Marvel has been looking for answers, but unlike its peers, they’ve doubled down on the tried and true rather than pursuing the new. Just this past week, Al Ewing, Dan Slott, and Valerio Schiti launched Empyre, its latest mega event designed to connect the universe via two of the publisher’s largest franchises in The Avengers and Fantastic Four. Then, in September, the X-Line will unite for the enormous, 24-part “X of Swords” epic, a crossover designed to be a rising tide that lifts all ships. 1 Lastly, King in Black arrives, as Donny Cates and Ryan Stegman are crafting a follow up to 2019’s Absolute Carnage storyline that elevates their larger Venom opus from an event with a lower-case e to one with an upper case everything.

And you know what? That makes sense in the wake of the pandemic. While it’s exciting to see innovation in a time of great disruption, there have been stories across many industries about how nostalgia has been a driver for consumer behavior during this crisis. 2 And in conversations with retailers, it has largely been the most nostalgic of all comic genres – superheroes – that have led the way for customers after the pandemic gap. Combine that with how essential long-term planning is for Marvel – its retreats are typically designed to plot the line out in at least 18-month segments – and it all adds up. It was the plan before, and naturally, it would be after.

But is it the right plan?

I don’t ask that to be coy, either. It’s honestly difficult to tell, especially when you consider that the prevailing theory about how events are bulletproof line leaders that positively impact the titles around them might not be quite as true as it once was. Marvel has long been infatuated with the idea of events as unbeatable sales tools, but are these uber-crossovers as valuable as they once were for the House of Ideas? Or are they yet another concept that the publisher has nearly squeezed the life out of, 3 making its 2020 plan questionable, at best? That’s what we’ll be looking at today, as we try to determine whether or not Marvel has turned one of its best solutions into a problem of its own.

Depending on what you call an “event” – and for the purposes of this exercise, I’m focusing on true line-wide (or at least close to line-wide) stories that have a broad impact, rather than including every crossover and vigorously hyped limited series – the modern era for that breed of story arrived in 2005 with Brian Michael Bendis and Olivier Coipel’s House of M. With apologies to Maximum Security, it was this fusion of Astonishing X-Men and New Avengers that found Marvel getting back into the event game with gusto, as it was the first in a seemingly endless wave of these kinds of titles.

It’s hard to say what triggered Marvel’s return to that path. It would have seemed counter to the publisher’s plans in-between its filing for bankruptcy and the arrival of that series. Before then, Marvel was going for accessibility above all, and events – stories that fuse disparate elements of a broader universe – are largely believed to exist in opposition to that idea. The one story I’ve heard that adds up is that it was then-Manager, Sales Administration and Publishing and current SVP of Sales and Marketing David Gabriel pushing it. This idea makes sense, as Gabriel joined the company in 2003 and was behind Marvel returning to variant covers that very same year. Whatever the reason, it was a move that worked, as the 2000s saw a troika of high selling, high impact blockbusters in House of M, Civil War, and Secret Invasion 4 leading the way in sales and forming a through line for the larger Marvel saga.

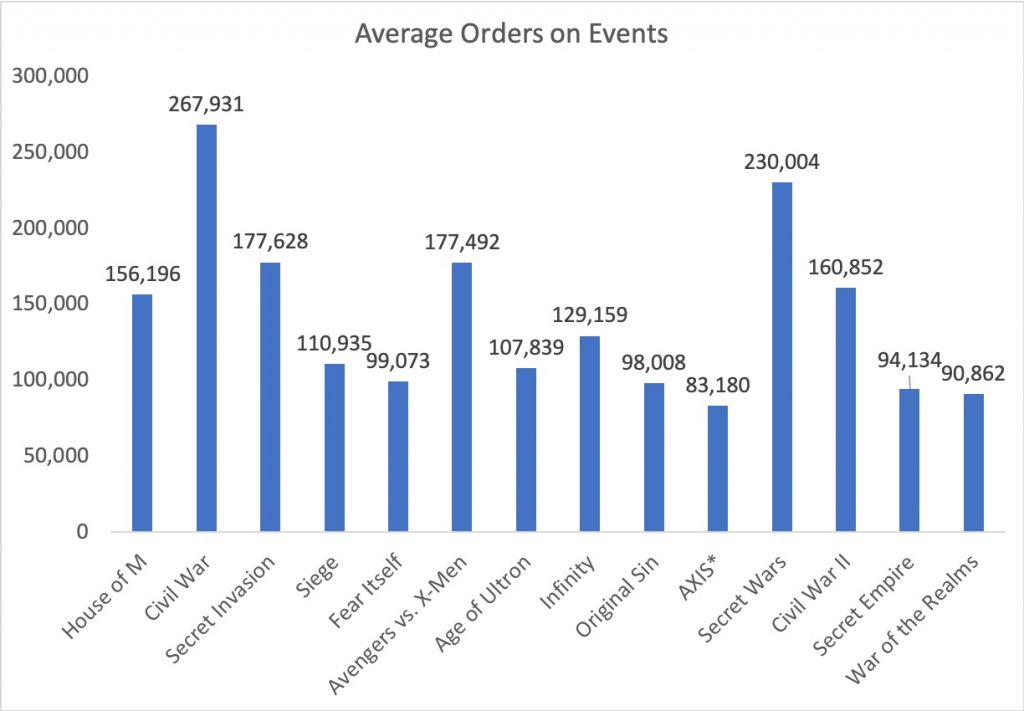

The heat was there, which Marvel clearly noticed, as deployment of events rapidly accelerated in the 2010s. They quickly went from specialized, impactful stories that happened every year and a half or so to line constants, with new ones popping up every half year for a lengthy stretch during that decade. We’ll get to the “why” behind that move here in a minute, but that punishing frequency led to diminishing returns, as shops decreased orders seemingly due to events just not having the same juice they once had with readers. To showcase that, here’s a chart with average orders on events, starting with House of M and ending with War of the Realms. 5

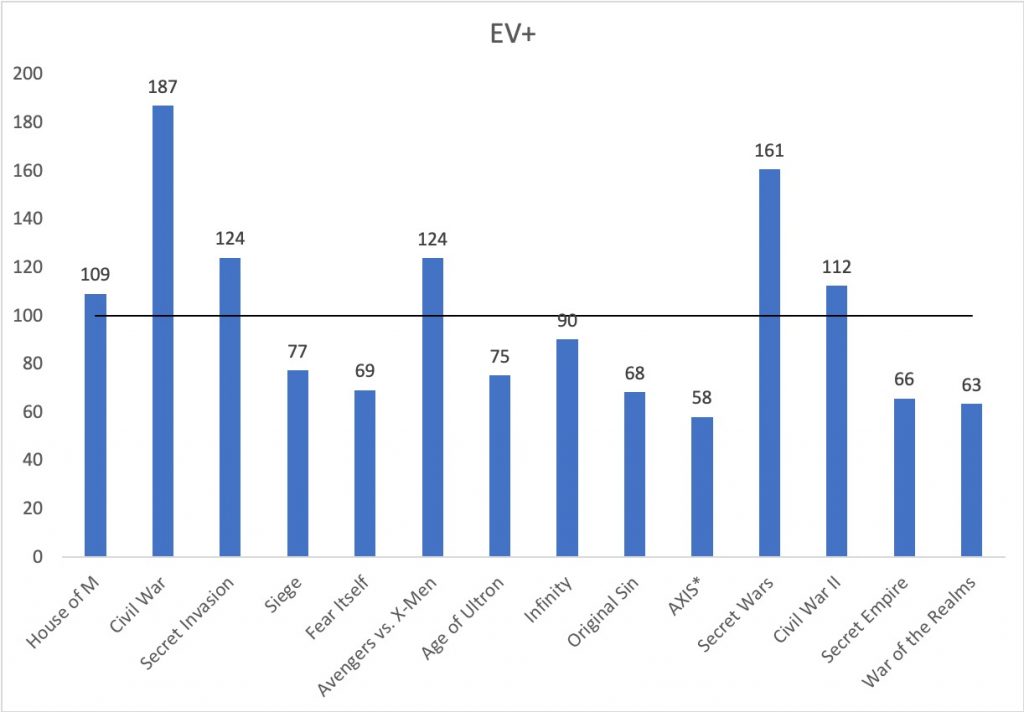

That says…something! It shows you the general shape and levels of interest in these titles, which is good. The problem with this chart, however, is it doesn’t contextualize for average performance, and I wanted to do that to ensure these numbers are easy to understand. So I’m going to steal a move out of my usual playbook of creating comic stats based off baseball ones. I’m calling this one Event+, or EV+ for short, with this being a bit easier to understand from a contextual standpoint. All you need to know to grasp this statistic is that 100 equals average, 6 and each digit upwards represents how much higher than average it is, while each digit downwards is the opposite. So 145 equals 45% better than average, and 90 equals 10% below average. Got it?

Here’s the chart.

Now that’s interesting. The first three events in the modern Marvel event era all performed at higher than average levels, with Civil War being far and away the strongest performer of the lot. Since then, only three of the 11 events have performed at better than average levels. Even worse, four of the last six make up the worst performing events of the lot, with AXIS lagging far behind everything else. That means only slightly more than a quarter of Marvel events are performing up to the publisher’s usual standards for events – even if they’re still doing well enough relative to, say, a random issue of Fantastic Four or Deadpool – with performance only worsening as time continues to pass.

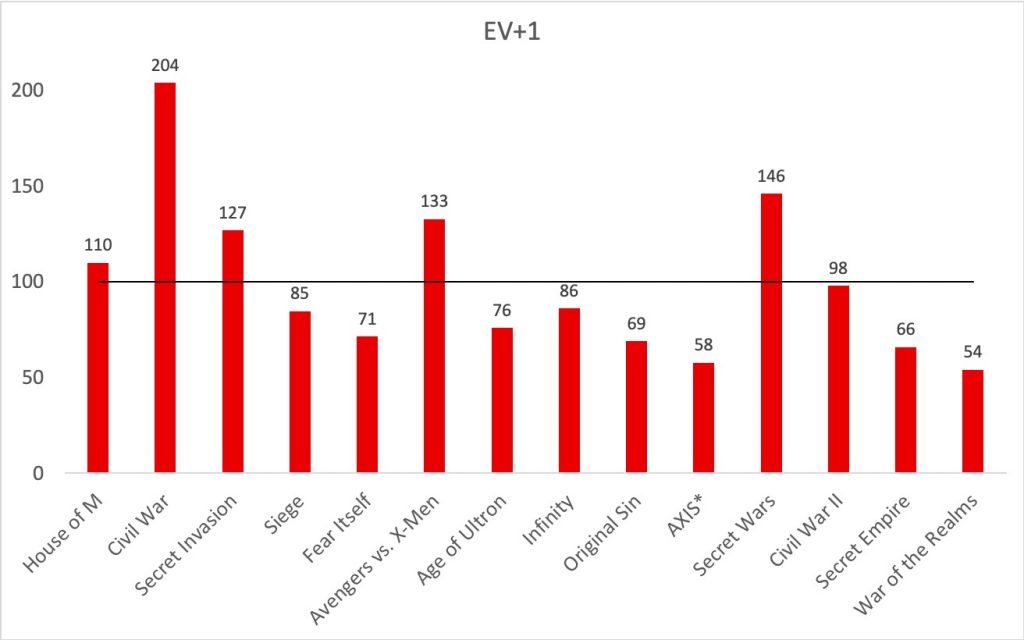

I wanted to make one more adjustment here, though, as one thing Marvel has done since that dip started appearing is it has front loaded incentives far more than before. While each issue of an event has a bevy of variant options, amongst other perks for shops, event #1s need a 90s Cable level of pouches to organize all the accessories they offer retailers. Those offerings create a bit of an inequity off the top, or at the very least an unrealistic view of average orders for these titles. Removing the first issues might reveal more predictive numbers. So what happens if we subtract them from the equation, then? Let’s look at that with another stat I’m calling EV+1, which, as you might have guessed, represents events after number one.

With that change, Civil War II drops out as an above average performer – its first issue was an outrageous outlier relative to the rest of the series – and we’re left with just two of the 11 events from the 2010s performing average or better. This change also leads to War of the Realms taking the bottom spot from AXIS, with it being ordered at just over half the levels of your average Marvel event. That illustrates the drop off Marvel events have seen over the years, as does this curious factoid: before Fear Itself, zero issues from any Marvel event finished outside the top five in monthly orders; since then, nearly 39% of issues have, with every non-#1 issue of War of the Realms even landing outside of the top ten. 7 That’s still solid performance, of course, and to a degree, the first Civil War was so successful it breaks this scale. But this information shows how merely existing isn’t a chart topping guarantee for Marvel events anymore.

They clearly know that. Gabriel told retailers in 2017 that after Secret Empire, Marvel was taking a break from events for at least 18 months, citing scheduling overlaps leading to readers being confused and tuning out altogether. To the publisher’s credit, they did just that. It was 24 months between the launch of Secret Empire and War of the Realms. They recognized the negative impact their aggressive release schedule had on events, and then they did something about it. That might make you believe they learned their lesson, but then again, Marvel’s rolling out two line-wide events and X of Swords just in 2020.

So maybe they didn’t.

That’s a lot of insinuation that events are broken at Marvel with little discussion as to “why” they are in retrograde. So why is that happening? Here’s where I do a magic trick. I’m going to guess the two words you’re thinking, at least in regards to the reasoning behind this. Ready?

“Event fatigue.”

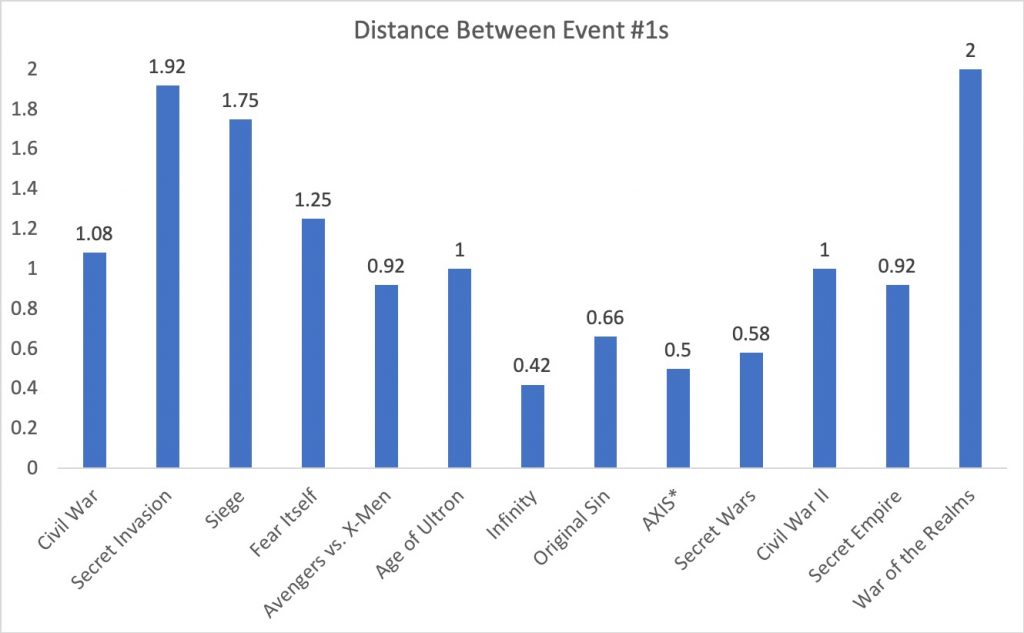

Was I right? Yes? No? Well, even if I wasn’t, the thought has probably crossed your mind over the span of this article because it is a commonly stated phrase in regards to this subject. And hey, I get it! Just look at this chart showcasing how Marvel’s rate of release shifted for events post House of M to see what I mean.

This chart tracks the length of time between the first issues of Marvel events. Those numbers are in years, and they highlight something I noted before: Marvel went from an at most yearly rate for event launches to nearly two events a year – with several of them overlapping – for a decent portion of the 2010s. And the wild thing is this doesn’t even include all of the secondary events or more narrowly focused ones, like your Chaos Wars, World War Hulks, Messiah Complexes, and beyond.

The case for event fatigue is, simply stated, nothing is important if everything is. It’s hard for these titles to feel like the game changers they’re meant to be when not even a calendar year passes between each story that promises to change the Marvel universe forever. The hype loses its luster when the event you’re reading has ads for the next crossover within it.

And yet, I don’t personally believe event fatigue is the problem people say it is, and a Marvel event is my evidence of that: Jonathan Hickman and Esad Ribic’s Secret Wars. It was the last release in that chain of twice-yearly events, and if event fatigue was the defining factor some might suggest it to be, you would think it would have been shredded by the frequency of gigantic stories that preceded it.

But it wasn’t. In fact, Secret Wars was by far the highest ordered event of the 2010s for Marvel, even discounting it for the massive number its first issue was ordered at and considering the harmful delays the tail end of the series went through. Using conventional logic, the deck was stacked against Secret Wars. But it flourished all the same.

If you look at Secret Wars, though, it’s easy to see how it separated itself from the pack. It was clear to any reader that this event was “important” and would result in real change, especially considering Marvel replaced its line with in-Secret Wars continuity for the bulk of its run. It had a broad focus, rebuilding the Marvel universe into a new Battleworld while incorporating a diverse mix of characters, even if it did have a Fantastic Four/Illuminati lean at the top. It grew organically from the story that preceded it, with that being Hickman’s extended run on Avengers and New Avengers. And lastly – crucially! – it was a very good comic, with a hot creative team doing its thing to the absolute max.

Now consider those four ideas: importance; broad focus; coming naturally from other stories; and quality. Then think of the other events from the 2010s. Then ask yourself how many of those events earn checkmarks for all four of those categories, or hell, even two of them? Your answer likely depends on subjective beliefs, but it’s inarguably a rather short list.

Conversations with retailers reflected this premise, as most agreed that Marvel’s events lack juice these days, with the dominant reasons reflecting those key points. Sometimes they’re too narrow, with War of the Realms effectively being a supersized Thor arc and Secret Empire stemming from Captain America’s two famous words. They lack real consequence, as stories like Age of Ultron and AXIS having effectively zero long-term impact. They often are undercooked with good artists facing compressed deadlines, leading to comics of frequently mixed quality. And in regards to importance, I wanted to share a funny coincidence that came up in my chats. When I broached this subject with shops, two separate retailers asked me some variation of “do you even remember what Civil War II was about?” The answer was “no” for each of us. 8

All this leads to my real “why.” I don’t think orders on events are down because the frequency of events is leading to event fatigue; 9 I believe they’re down because the frequency is leading to mediocre comics that serve little purpose beyond tying into movie releases and goosing Marvel’s bottom line. 10 It isn’t the readers tiring. It’s the concept, as it exists simply because it must, not because there’s something worth telling necessarily. Because of its obsessive, recurring belief that events should define its line, whether the story is there or not, Marvel has diminished the potency of this breed of story and made both readers and retailers question whether these titles are worth the hype at all.

That’s a problem.

On the surface, you could read all of this as Marvel is overcommitted to an underperforming idea. That they’re such believers in the promise of events that they think any iteration of one – regardless of fit or value – will work. But we now have a decade of evidence that proves this isn’t necessarily true, even if events are still solid performers, just not relative to what they once were. 11 Those peaks are still potentially there, though. These bigger stories can still thrive if they’re given real focus, weight, organic feel, and a creative team with a big idea in its back pocket. Secret Wars proves that, as do House of X and Powers of X, even if those aren’t an event in the sense we’re discussing. 12

Unfortunately, that’s all too rarely the plan at the House of Ideas. It seems clear that outside of the post-Secret Empire gap, events are a rigid part of Marvel’s overall structure, the milestone everything else is built around. And hey, sometimes that leads to greatness and sensational sales. Most of the time, unfortunately, it leads to stories that feel forced and ones that lack enthusiasm amongst readers. 13 With that in mind, it’s not a question at all: coming into 2020, Marvel was absolutely facing an event problem. Its actions and approach were resulting in reduced performance and excitement in a type of story that was once its bread and butter.

That made its decision to commit so wholeheartedly to events this year a questionable one, at least initially. Just a couple weeks ago, shops were universally reporting to me that Empyre had zero interest – one shop described its heat amongst customers as “ice cold” – and that was before King in Black was even announced, ensuring that readers were looking to tomorrow before today even arrived. If I told retailers in January that Marvel was going to publish three event-sized books in 2020, they likely wouldn’t have even responded. They would have went straight to their Marvel reps with a flurry of obscenities.

But that was before the pandemic, and it was in a much different consumer environment. Now? We have a last second twist. While shops were unified in agreement that before this year, Marvel had burned a lot of bridges with its events, the pandemic and the corresponding discontinuation of new single-issue comic releases for about two months has led to unexpected behavior from readers. Empyre, once projected as dead on arrival, was a solid to above average performer for the bulk of the shops I spoke to, albeit with some outliers in the mix. 14

The reasons for that were varied, but there were two dominant stories from shops. First, the pandemic resulted in a paring down of Marvel’s line, particularly when it came to Empyre tie-ins, making it a much more manageable read. Excising a slew of tie-in titles made the whole thing feel more approachable to readers. Second, that gap in releases led to a desperate thirst amongst comic fans for new material, with a repeated emphasis on meat and potatoes superhero titles being the most desired menu item. There’s nothing more meat and potatoes then an event, especially one that was considerably streamlined. 15 That resulted in several shops selling out or at least getting close to it, which is impressive work considering the frigid buildup, even if orders were lower on Empyre than they usually are for an event.

So again, that’s where things get weird. In any other year, I’d say Marvel is 100% facing an event problem, but my read on it after talking with shops is that the pandemic gap has led to a reset of sorts for consumers. In a time of incredible uncertainty and anxiety, readers – like Marvel – have retreated to the tried and true, finding comfort in the nostalgic trappings of these giant crossovers.

That makes this whole premise tricky. There’s almost a “before coronavirus” and “after coronavirus” 16 effect going on that destroys the value of comparisons. The direct market is just operating from a completely different paradigm than it was before, and bizarrely, the post-pandemic gap era very well may be more event positive than the one that preceded it. Events – even ones with little hype – are seemingly connecting with readers, at least amongst the shops I spoke to.

Is that sustainable? Will those good feelings last through the weekly Empyre – especially considering the first issue itself was met with a resounding thumbs down from those I spoke to, with one shop straight up telling me it was “bad” – 24 issues of X of Swords and what will assuredly be a deluge of King in Black and King in Black-adjacent releases? Who knows, to be honest. I’d have bet against it just last week. Now? I’m not betting on anything. The pandemic has made the prediction game effectively useless.

What I will say is this: while I think Marvel needs to drastically rethink the way it uses events going forward, as they’re clearly not as effective as they once were, in the wild, wild west that is 2020, going event heavy very well may have been the right play. These are the kinds of comics that get people talking and, crucially, get people committed to buying, if only out of their fear of missing out. Strangely, Marvel’s event filled plan may have been saved by the pandemic, serving as just what readers wanted during a time of great uncertainty. Again, is that sustainable? Maybe not.

But sustainability is a concern for an ordinary year. When the name of the game is survival, even something that may not be what it once was for Marvel like events can be the right solution for retailers problems.

Well, as long as they have an “X” in the name.↩

Even oft forgotten collectables like sports cards and memorabilia has seen considerable lift amidst this.↩

Like variants, for example.↩

World War Hulk doesn’t count in my structuring, as it was more a localized event extending from “Planet Hulk.”↩

As per usual, all sales data comes from Comichron. Also, in the situations where an event had a zero issue, those were omitted for consistency reasons, as shops almost universally ordered those far lower than #1s.↩

With the line through the center of the graph representing 100.↩

You might have noticed the asterisk on AXIS. That’s there because its first issue came in at #5 in orders from shops, an idea that was a virtual impossibility before it happened.↩

I will admit, though, that one of the shops and I eventually pieced it together during our conversation.↩

If that was truly the cause, you’d think Forever Evil would have been a monster at DC given that it was the New 52’s only real event comic, with a three year gap on each side of it. Instead, it was a forgettable, underperforming event with no lasting impact.↩

For a similar premise, look to the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Amongst the four Avengers movies, Age of Ultron was by far the worst performer, and it wasn’t because Marvel enthusiasm had dipped. I’d argue it was because it was by far the worst of the four.↩

Even something as middling, event-wise, as War of the Realms or AXIS is a relative monster in the direct market.↩

It also shows that hiring Jonathan Hickman for these kinds of big stories is a pretty good plan!↩

Unless you consider anger “enthusiasm,” in which case Secret Empire generated considerable enthusiasm.↩

While that perspective didn’t come from a representative sample of shops, it’s still interesting on an anecdotal basis.↩

Bizarrely, this same phenomenon is, I’d wager, at least part of the reason X of Swords swelled to its considerable size. Marvel is doubling down on what works to combat a time of great uncertainty, and while Empyre‘s hype was sketchy, at best, the Hickman-era X-Men line is still en fuego.↩

Or, more realistically, “during coronavirus.”↩