SKTCHDxTiny Onion: Part Ten, A Halloween Horror Chat

As you likely know, today is Halloween.

As you also likely know, James Tynion IV? He’s fairly good, and prolific as well, at telling horror stories in comics!

Is it any surprise that we waited to run this month’s SKTCHDxTiny Onion conversation — one about his personal history with and love of horror, and how he approaches the genre in his varying comics, most specifically in his latest books Universal Monsters: Dracula and The Deviant — for the holiday most closely associated with scary stories of all varieties? I’m sure it isn’t. But that’s what we have in store for you today, and it’s a fantastic conversation with one of the true masters of horror in comics.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity, and is open to non-subscribers. If you enjoy it, consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more like it, and make sure to subscribe to Tynion’s The Empire of the Tiny Onion newsletter over on Substack while you’re at it.

Also, if you missed any of our previous conversations from this year long interview series with Tynion, you can read them at the links below:

- Part One, The 2023 State of the Union

- Part Two, How to Build a Comic

- Part Three, Dealing with a Changing Market

- Part Four, Planting a W0rldtr33

- Part Five, Thinking Globally

- Part Six, On the Power and Perils of Variant Covers

- Part Seven, Prioritizing Yourself

- Part Eight, Crafting a Debut

- Part Nine, Collaborating and Collaborators

It’s October. Spooky season. Halloween time. In fact, this chat will run on Halloween itself. With that in mind, we’re going to be talking about horror this month, which makes sense because that’s the genre you’ve become known for above all, I’d say. That’s where I want to start. Why horror? What made that genre such a focus for you as a writer?

James: It’s been a deep fascination my entire life. I didn’t start watching horror movies very young, but I started being fascinated by horror imagery very early on. I was drawing skeletons. I loved Nightmare Before Christmas. All of that. But my early engagement with the horror genre was walking down the aisle of Blockbuster and not making eye contact with any of the covers of the videos on the shelf, because if I looked at the covers, then I would have these really bad nightmares.

But then late in high school, I started realizing that the stories I was making up in my head were actually scarier than the actual movies. I started becoming fascinated by that fact, and I started writing down the stories that were in my head. So, that interaction with horror is where the impulse for me to write stories comes from and in processing my fears through fiction, both about myself and the world around me is the lens through which I know how to write.

So, without even thinking about it, you just kind of started processing your fears from the start through story. Then next thing you know, it was just happening naturally. In a weird way, horror set you on a path to becoming a writer at all.

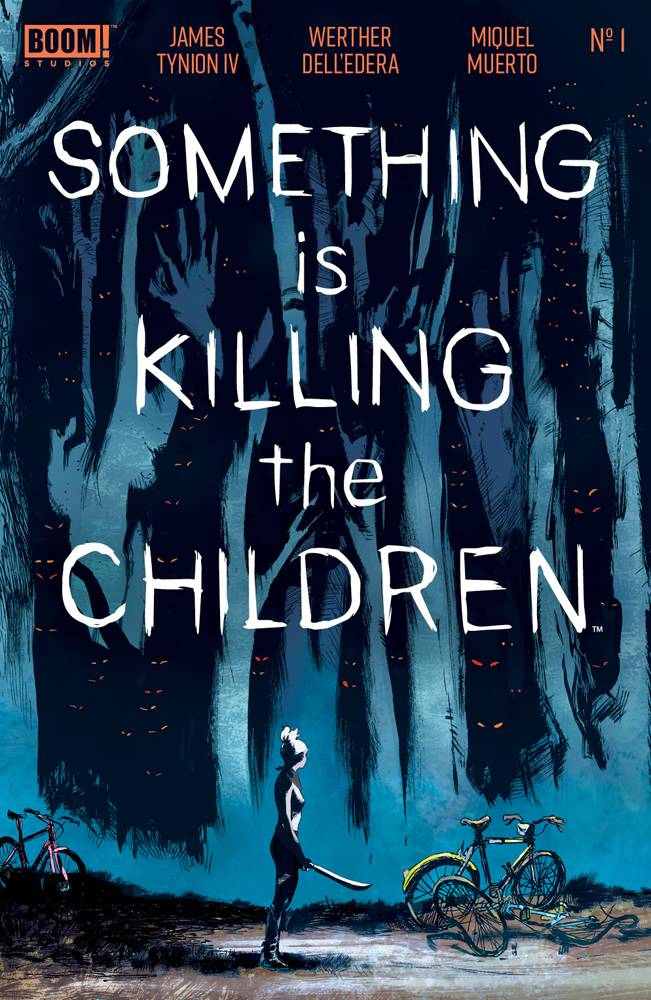

James: Absolutely. You see a little bit of this in the first scene of Something is Killing the Children #1, which pulls from my real life. I used to have these very vivid nightmares, and at sleepovers with my friends, I would tell my friends my nightmares. At a certain point I started realizing that it’s just like, “Okay, I actually have to heighten certain parts of the story to scare them.” And even though I was a kid who was just like, “I don’t like horror. I don’t want to watch a horror movie. I’m too scared to do any of that,” I was sitting around and telling my friends scary stories that came from my mind. The joy and pride I felt that I was able to unsettle my friends, that was the lasting feeling. And, yeah, everything comes from that feeling.

You just said Something Is Killing the Children. First scene, the character was literally named James, wasn’t he?

James: Yeah.

And then there’s Nice House on the Lake.

James: I’m very subtle about it.

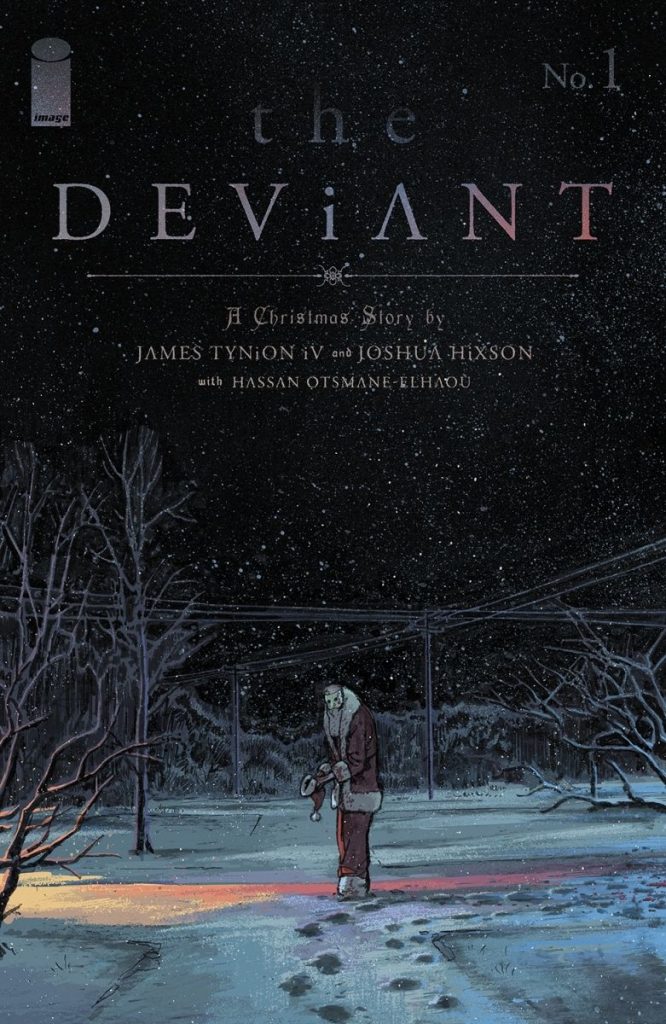

There’s Walter. This one might be more of a reach, but in The Deviant, there’s Michael, a comic book writer who is looking to write fairly similar stories to what you write. And in those three, your proxies were the victim, the villain, and then sort of the critical observer. Is it easier for you to process your fears and to tell stories built off of them if it’s also to some degree an analysis of yourself?

James: Absolutely. And it’s one of those things where I used to be more self-conscious about it, but I figured that if Stephen King can write proxies of himself for decades with multiple novels out a year, I can get away with it a few more times. My fiction has always been processing my life. It’s the fuel behind the stories. Everything I write is me processing the world and how I live in it. Even stories that I think people wouldn’t necessarily assume come from that place often do, and often in much more literal terms than I think people expect. There are people in the closest rungs of my life who know like, “Oh, there’s an entire scene in insert-comic-here that is just literally taken from this very harrowing moment in James’ life.”

I do that stuff constantly and it gives me these emotional touchstones. And I think that it also comes back to horror there, where horror is about eliciting an emotional response in the reader. If I can’t elicit an emotional response in myself, I know I can’t do that. I can’t make somebody else feel it. So the emotional touchstones of myself and what make me feel big things always have to be at the center of what I’m writing. I do feel like there are limits to that. I think that over the next handful of my projects… There are a few projects I’m developing that have sort of a James character in them, but I am trying to deliberately move away from that. Like in w0rldtr33…w0rldtr33’s closer to how I handled The Woods, in that almost every character in that has an aspect of myself.

So, every character is tapping into something real and authentic in me, but it’s not creating a comprehensive image. There’s nothing autobiographical about w0rldtr33. It’s just I take real emotions and then I use that to fuel moments and scenes.

This might be a complete aside, but people talk about the idea of self-inserts where authors or whoever is putting themselves into a story as if that’s a bad thing. But people have been putting themselves in stories since stories existed. You build from what you know. What do you know better than yourself? Putting yourself in the story is not a bad thing for storytellers. It’s a natural thing. And it seems like something that has really helped you figure out how to tell stories in a way that makes them universal because you understand them yourself.

James: Somebody said this that wasn’t me. There’s a more comprehensive version of this that’s a nice quote from a very smart person. But there’s a universality to specificity. The more you zoom in on very specific human experiences, the more people can plug into that. That essential piece is something that I’ve been chasing in all my work. Honestly, some of this is still a reaction to my superhero work where I was plugged into a very different fuel source for most of my superhero work. The thing driving all my superhero work was my fandom of these characters and these worlds and these stories that I had grown up with. I would put little pieces of myself in and I would lean into how these stories specifically spoke to me.

But then once I used up what I had to say about why I was a fan of these characters when I was 13. I was scrambling to figure out, “Okay, what feels authentic and what makes me want to write this story?” I’ve never once felt that in writing my creator-owned work. I think part of it is, I’ve been freed by the fact that the more self-indulgent I’ve gotten in my writing and the more I’ve leaned into self-insert characters and all that (laughs), the more successful my books have been. At this point, I’m doing what feels best to me as a writer, and that just so happens to be, at least for this moment in my career, what readers want most from me, which is a really cool, valuable thing. (laughs)

So, Something is Killing the Children pops off. It becomes this giant hit. And then you have…I’m trying to remember what was next in order. Was it Department of Truth?

James: Wynd kind of snuck in a little earlier in that, but then Department of Truth close on its tail.

Yeah, and then The Nice House on the Lake and then we go down the line. I imagine at a certain point readers started seeing you as the horror guy, the guy they can trust that is going to deliver a story that will connect with their fears and hit them in a real way. Was part of you becoming the horror guy by design because you’d already found a lot of fans who enjoyed your horror writing and you wanted to lean in, or was it less specific than that?

James: I mean, it’s a little of column A and little of column B. A lot of it is I come up with the most horror ideas out of any type of idea I have. Even the non-horror ideas I have tend to have horror elements to them. But I mean, it’s also listening to what people respond to. I think an example I brought up before is just the market can sustain multiple horror books by me running concurrently but I won’t try to do another YA book until Wynd is done.

I think that that is the right move for me because I don’t have as large of an audience for me delivering that type of story. It’s still very authentically me. It’s still a genuine expression of types of stories I want to tell. I have other ideas in that space, but honestly, my horror work, I’m able to talk about so many different things about myself, about my life, about my fears, about the world that I never feel like I’m boxed in by it.

At least at this point in my career, I’ve never had a shortage of ideas. If I had to right now lay out every idea that I have as a publishing plan for the next decade, I could because I have the ideas that are already cooking. In the same way that when I talk about…I think I pitched w0rldtr33 the first time in 2018 or something like that. I have things right now that will come out in four years that are already starting to form. I did a long walk on Saturday putting together the pieces of one of those stories and I love that.

Most of those stories are horror stories. They speak to me. The aesthetics speak to me. The things that I think I do well are suited for horror, particularly in the comic book realm because there are certain things that comics horror does very well, and there are certain things that actually comics horror doesn’t do well.

One thing that helps in that regard is one of the underrated superpowers of horror: it’s extremely versatile. Just look at your work. w0rldtr33 and Something is Killing the Children are way different horror stories. And then your two latest releases, Universal Monsters: Dracula and The Deviant, those are massively different. I feel like combining all the different ways you can kind to express yourself with all the different ways that horror can work as a genre, it allows for an incredible amount of flexibility for a storyteller that’s looking for flexibility within that space.

James: Yes.

Do you deliberately aim for different flavors of horror when you’re developing projects like Dracula and The Deviant?

James: Sure, and I think I try to not stack too many…I’m not going to do another sci-fi, techno horror while w0rldtr33 is still running. If I have another idea in that space, that idea has to wait until this story is done. There are other things that I want to do in the serial killer space that might lean more towards a slasher vibe than what we’re going for with The Deviant, but I’m going to wait until after The Deviant to do those types of stories. It is one of those things where I want to make sure there’s a slightly different flavor of every book that you can get from me at a given moment.

But yeah, it’s always a conversation. It’s always figuring it out. And sometimes the thing that overpowers it all is, what am I feeling the most in a given moment? And sometimes there is an immediacy of feeling that I need to express in a comic. I’ve been doing Sandman Universe: Nightmare Country, and the current miniseries is wrapping up over the next month or so. And then we’ll wrap up that story starting next year, but honestly, it’s sometimes when you’re playing with other people’s toys that then you can then suddenly adapt to like, “Hey, here’s something big happening in your life.”

So, I’m going to veer in a strange direction and just write an issue that wasn’t in my brain until five things happened in my real personal life that I actually am trying to unpack as a person. And then it creates this very visceral feeling in reading the comic and writing the comic, and it’s just like…I want to lean in. Sometimes, I want to just grab the live wire and see what happens. I can’t always do that because that is not emotionally healthy, but sometimes I do want to lean into what I’m feeling most when I’m feeling it most, and see how that effects my writing.

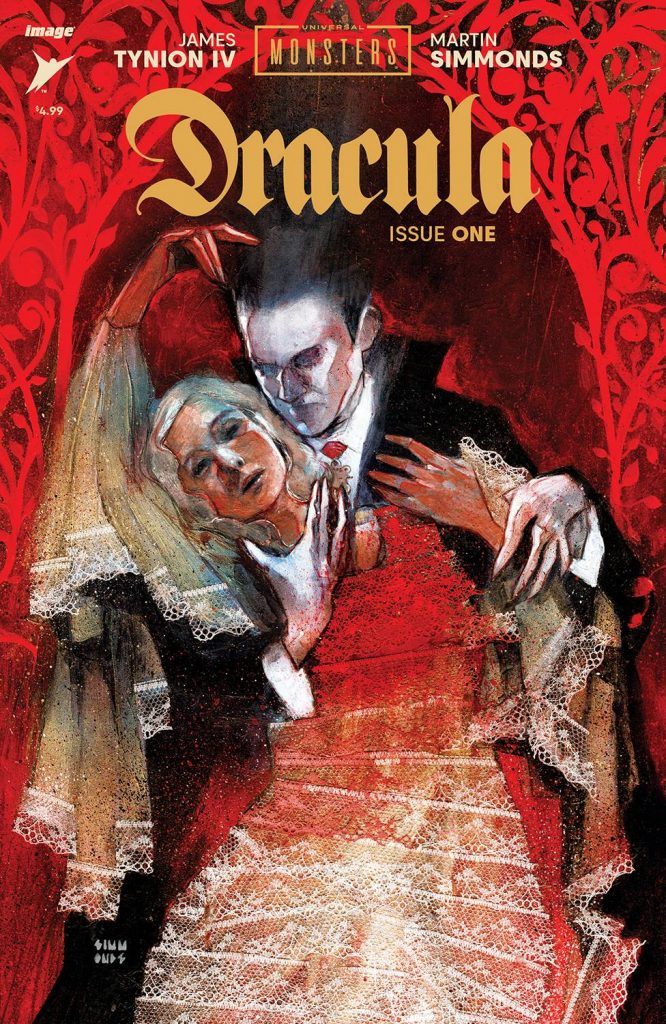

And it’s about opportunity as well. For example, Universal Monsters: Dracula…that was something (Skybound Editorial Director) Alex Antone came to you with.

James: Yeah.

Two years ago, if you and Martin (Simmonds) were in the middle of Department of Truth and Skybound was like, “Do you want to do this?” you probably would’ve said no. But you happen to be in the right moment to tell a Dracula story with Martin wanting to do something that’s more horror oriented. Next thing you know, you’re telling a Dracula story that you probably wouldn’t have expected.

James: Yeah, and it’s fun. I mean…this is the real thing. I’m very aggressively in the mindset right now that my day-to-day work for the next five, 10 years of my career at least is all going to be creator-owned comics. I am not interested in playing with a lot of other people’s characters, but every now and then I enjoy getting to dig into a sandbox that doesn’t belong to me. I think it’ll be a while before anyone can expect something new in the superhero space for me, or at least in the big company owned superhero space. I might have a few superhero adjacent ideas on the back burner, but those would be creator-owned books.

I’m very happy that Dracula came exactly when it did. But the thing that makes me happiest about Dracula is it’s an expression of a lot of kinds of writing that I don’t get to do as much of in my creator-owned work. First off, it was a challenge. I gave myself a lot of very firm rules. I wanted to follow the continuity of the original film as best as I could. I’m putting together the last few pages of the last issue right now. That was a difficult trap to lay for myself because I’m also trying not to just duplicate scenes from the film, but I am trying to reflect them. So that can be…I think towards the end you have to actually see the death of Dracula. (laughs)

I like giving myself a creative problem. I like playing with these toys and trying to bring some of myself into them. But mostly, it’s a vehicle to show off Martin and unleash him in very spooky ways. And then there was a whole moment where I was going to lean into…I don’t know. I guess it’s spoilers. I shouldn’t say, but I’ll say it. Everyone knows the story of Dracula. You can’t spoil Dracula. I was going to lean into a more redemptive arc for Renfield, and then I realized this is a fucked-up horror story. Renfield’s death at the end of the original universal story is incredibly tragic. I wanted to lean directly into the tragedy of that death, and it is because he has this moment where he is almost helping the good guys take down Dracula, but then he succumbs back into the power of Dracula but then still dies.

I messaged a friend like, “I was going to have this whole big redemptive scene with Renfield, but instead I’m just going to have him eat a bunch of rats on panel because this is a fucking horror comic.” (laughs) And that was the right decision. It’s going to be more visually interesting. I love a creative problem to solve. I love a creative prompt, and that is the thing that the Universal Monsters (offer). I may or may not be doing one other monster down the line. But the whole point was I want to work with artists I fucking love, who I think are going to deliver an incredibly beautiful comics experience. And I am going to lean right into the images you can only lean into these iterations of the characters, and I’m just going to have as much fun with it as I can in-between all my other work.

My big takeaway from this comic, and I know it probably shouldn’t have been my big takeaway, but as I was reading it, I had this feeling that Dracula is the most fun you’ve had writing in a while.

James: That’s interesting.

I don’t know why. It just felt like you and Martin were really basking in it. You love your other work, but in this one, there’s freedom in knowing that there’s a structure behind you that you had to lean into. And when I was reading it, it just seemed like you had a really good time writing Renfield and everybody else in the book. I don’t know why that was. I could be completely off base, but when you said you were having a lot of fun, I’m like, “Maybe it’s just an ordinary amount of fun for you, but it just seemed like you guys were having a good time.”

James: It is, and honestly, I think there’s also something where the weight is off a little bit. My other work is obviously much more deeply personal to me. I am expressing a real thing from deep inside my soul and blah, blah, blah. With Dracula, I’m having fun with my friend and making him draw really cool Dracula pictures and that feeling is also key to the comic making experience. It’s making cool shit.

Making cool shit is a central driving ethos. It’s something that I want to be at the center of what I do in my career… At this point, I have other smart ideas and all the shit that I’m going to do. But in the next few years, you guys are going to see a few more instances of me having a weird idea that I want to see an incredible artist draw, and I am very excited for those experiences too because it’s the fun of it. It’s the play that I think we’ve talked about before, that there is an element of play that needs to exist in the creative process for me.

And then horror is such a great genre to play in because it’s all this imagery. It’s what I’m naturally drawn to. My comics are usually talky and they’re pretty dense. And there were whole sequences of Dracula where I don’t need any words. I am just going to describe what I want to see Martin draw. And the joy of getting those pages back is immense. I picked up one of the pages from issue #1 at New York Comic Con. And Martin’s pages are these glorious hand-painted pages. I got this page from the book (James holds up a page), and it looks identical to this. He did all the coloring on the actual page. He did a little digital touch-up, but it just looks like the page in the book. That’s just so fucking cool.

I was kind of hoping you got the title page. The title page is so crazy.

James: I claimed the initial Star Face Man double page spread from Department of Truth. With this one, I was like, “I’m going to leave Martin all the Renfield pages to sell and I’m going to leave the spreads for him to sell.” I’m not going to try to claim something that he could make some good money on because I already have five Martin pieces around my apartment.

Can’t be too greedy.

You taking on this project reminds me of when we talked in the past about the importance of taking in other inputs. Maybe it is a surprise, like, “Why would he go back and do a for-hire book that’s about Dracula from the Universal Monsters.” But sometimes it’s not just about watching something different or reading something different, it’s about doing something different and forcing yourself into parameters you wouldn’t normally exist in. Because I imagine there’s going to be things that you take away from this and Martin takes away from this that you feed back into the Department of Truth or your other projects.

James: I think Dracula is Martin’s best-looking work to date. And if you think we’re not going to go back to Department of Truth with the goal of beating that, you’re crazy. Because it’s just like, “No, Martin’s best work needs to happen in Department of Truth,” so now we need to one up ourselves. And that’s a fun challenge that I’m very excited to set down for ourselves.

I read another interview you did about this where you said that Dracula is basically a showcase for Martin, and I think that’s one of the things…I have a friend who loves horror movies and loves horror stories but doesn’t love horror comics. They never work for him. But sometimes horror comics can be negatively impacted by ill-fitting art. And it seems to me that a key part to making something like Dracula or w0rldtr33 work is having the right partner. Is the key to making horror visuals work more about style or storytelling? I imagine it’s a bit of both really.

James: Oh, yeah. I mean, good comics are always about the synergy of those two things. But like I said before, there are things that comics horror doesn’t do particularly well. You can only surprise the reader once every two pages. Because the way that people read comics is once you do the page turn, you kind of glance at the entire spread and then you go to the first panel of the top of the left page. You can’t hide a beat later in that moment. The other thing that fucks with horror in the comics form is that the readers set the pace at which they read a comic, and horror is all about timing. It is all about that steady drumbeat.

In Stephen King’s Danse Macabre, he lays out the different stages of horror. I wish I remembered them all right off the bat, but the two that I know that comics do very well are dread and the gross out. And the gross out is the basest thing that you can do in horror, but it’s still a very effective move. Arresting the reader with an image that’s just so grotesque that you can’t look away. It’s the cheapest move in the horror deck, but it is also one of the most valuable moves.

And then there is dread, which is just about a pervading sense of something wrong, and it’s uneasiness and it’s making you anticipate a horror moment. So, this is why I play with density of information on pages a lot of times. That’s me trying to take control from the reader in terms of how quickly they’re reading the comic. By adding density of panels and density of dialogue, it means that you have to kind of slowly read through what’s happening and follow the pace I want you to follow.

And then when I want to hit you with a fucked up idea or fucked up image, I can surprise you with it. I think those are the touchstones of how I work because I also try to make sure that moment doesn’t happen when you expect it. That’s a tool you see in horror movies. Usually, it’s like when the music is trying to make you anticipate something that then doesn’t happen. I’m trying to do that over and over again in my writing. I try to cut sideways through a scene with something — either a particularly brutal line or a particularly brutal image — And I try to make those things happen at moments you don’t expect. I want you to be feeling dread when you’re reading every single page of the book.

I was just talking about this with my wife the other day as I was flipping through the bootleg edition of Department of Truth. I was telling her about how you do final pages well, but you often will bury the scary moment in a place you don’t expect and how that always messes with people’s rhythms. That’s one of the huge things about storytelling, particularly with horror. If you give people what they expect every time, they’re not going to love it. It is not going to hit them in the same way. When you can mess with those rhythms, or you put that scary bit on page 16 instead of page 20, then the next beat hits 20% harder than it would’ve otherwise.

James: That’s the key thing. First, you have to make people care about the characters, so they care about what’s going to happen to them. And then it’s all about timing. It’s all about pacing. The rhythm of a comic is what I spend the most time thinking about. I think I have a particular strength at comics pacing, and it was trial by fire to get there. At this point, I understand what a single issue feels like and what a full arc feels like. When I started just writing dialogue flows that then I would carve up into comics, I would end up with five to 10 extra pages. That doesn’t happen anymore. I know what fits into a comic book. It feels good. (laughs)

I don’t know if this counts as gross out, but this is a funny thing to say that I thought was maybe the scariest bit of The Deviant. In The Deviant #1, there are two times see the killer that’s on the cover, the Santa Claus killer. And the way that Josh (Hixson) draws him is deeply alarming to me. His legs are so long that it’s really disorienting and kind of freaks me out. It makes him feel unnatural in a way that I don’t know if he’s supposed to be a person or if he’s not supposed to be a person or what. But when I got to that bit, I just was freaked out. I was like, “I don’t want to look at this guy anymore,” but then I immediately started bouncing back and forth between his two appearances to look at his freaky legs.

It’s weird how there can be these singular images that are just 15% off and it just freaks you out. Not in an uncanny valley way but in a genuinely scary way. Josh totally tapped into that with this villain.

James: That uncanny sense is what I feel like we’re always shooting for in horror. And when you have a partner who is going to deliver an image like that, that’s so valuable. We could tell from the first cover and all that, but that first two-page spread in the book, the big image of the killer in the first issue…when Josh drew that, it was just like, “Alright, we’re cooking.” This book is going to succeed at what we’ve set out to do.

We talked about how your sense of self is always in these books, but do you feel like Dracula and The Deviant speak to different sides of yourself as a writer and as a horror person?

James: Sure. Dracula is much more about my love of the history of the genre, the big mythologies, the big figures. It’s much more primal. It’s much more about good and evil. And most of my stuff doesn’t really tap into that. Honestly, I wanted to lean into that sense of pure good and evil, and I wanted to frame it in the terms that I think a lot of my work focuses on right now when it comes to the central themes. I think that the defining trait of humanity is the fact that it’s kind of messy and ugly. I want to lean into that. And you’ll see that, especially once we bring in our version of Van Helsing, who’s a much less pious figure than previous iterations, but still comes from this very humanist perspective.

I wanted to tap into that, but it is still good versus evil while The Deviant is all grays. The Deviant is me entirely just picking at ugly fears of myself and my place in the world. It’s tapping into the strangeness of having gone to high school 15 blocks away from the apartment building that Jeffrey Dahmer killed all those people in about 10 years after it happened, and how that shaped my vision of what a queer person was, and how that was internalized and then made external later. It’s a story that’s meant to be uncomfortable and all that, while Dracula is me tapping into much more the fun of the genre.

But The Deviant also has a scary Santa murderer, so I think there’s still an element of fun there too. I’m always going to do the thing where I bring in my key visual element that makes it feel like a comic book. With Dracula, there wasn’t any question of finding that. The key visual element was going to be Dracula, although there was still a discovery process there because I didn’t describe Renfield in the way that Martin drew him. And the second that he drew Renfield, I was like, “This is going to be the lasting image from this book.” If there is a lingering piece that people remember, it’s going to be Martin’s Renfield.

It actually really reminds me of the killer in The Deviant in that there’s something unnerving about the way he does Renfield. His face kind of disappears in some panels because it’s so white and just blends with everything. It’s very alarming.

I think one thing that’s interesting about horror as a genre is once upon a time, it was believed that horror did not work in comics. It just didn’t sell. And when I was growing up, it was perceived as a cheap niche movie genre. These days, horror has become a genre that is about as consistently commercially successful as any of them, and across a number of mediums. Why do you think that is? What do you think it is about horror that resulted in it becoming a lot more universally liked in a way that it wasn’t when you and I were coming up?

James: I think all of this comes in cycles. There have obviously been cycles where horror films were seen as high culture as well. When Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist came out, those were recognized as serious films, not just schlocky B-films. But it then shifts back to the background. And frankly, I think horror is always shaped by cultural fears. At the moments that the world is scariest, we go to horror more often, and the world’s pretty fucking scary right now.

So there’s more to be gleaned from playing with your fears and interrogating your fears when you have more fears. And I think horror also becomes a place of comfort, which once again, it has been in the past. The lasting popularity of the Universal Monsters shaped an entire generation of monster fans. Same thing with Godzilla movies and things like that. There have been kids who have grown up with each successive generation of horror icons, going back a century. But it waxes and wanes.

I think we’re in another moment of horror icons and iconic horror storytelling happening and it being very commercial. But I know I’m going to live through a few cycles of this in my life. Some of it is make hay while the sun shines. And right now, horror is clicking. Horror is one of the things I think I do best. So I’m going to make a lot of horror, and then hopefully that sustains me through the lean years. (laughs) I think I’ll tap into other aspects of what I like to write even when that day comes but I’ll still keep writing horror.

Stephen King never stops doing horror novels. He just also throws in a Western every now and then. That is how I think about it and feel about it. But I think that we are living through a real renaissance of the genre, where it’s just in a way that I never thought we’d see coming back, where you’re seeing more paperback horror come back in the fiction space. There are so many films. There are so many comics. Junji Ito is a brand that you can get on T-shirts at your local mall. That’s a cool thing. It feels cool to be a part of a horror moment like this, but nothing lasts forever.

If you enjoyed this conversation, consider subscribing to SKTCHD for more like it, and make sure to subscribe to Tynion’s The Empire of the Tiny Onion newsletter over on Substack.